History is a thing we are always making. Or, at least, the experiences that collect around us as we move through the world are stories capable of historicization, even though so much is forgotten or passes unremarkably. Some things, though, need to be recovered and told again. Why re-tell a story? And how to tell it?

In Sofia Coppola’s The Bling Ring (2013), she recalls the real-life escapades of a group of young adults who burglarized celebrities’ homes near Los Angeles in 2008 and 2009. In Coppola’s telling of it, the kids were motivated by a base obsession with fame and riches, enabled by a fluency with electronic media. By stalking stars online, the Bling Ring, as they were dubbed, were able to capitalize on the absences of the celebrities from their homes. Victims included Audrina Patridge, Lindsay Lohan, and Paris Hilton, the latter of whom even makes a cameo appearance. Strangely, despite the fact that their identities are widely known, members of the Bling Ring were given new names for the adaptation, while the celebrities and their celebrity statuses remain. In this way, The Bling Ring re-performs the very obsession that fuelled the burglaries: a base fascination with stardom. One gets the sense that this film will age badly. The story is mind-numbing, and the film is not able to transcend the basic facts of the case. The representation of reality is both too close, in the case of the name-dropping, and too far: the viewer isn’t given any reason to care, not even given a reason to care about not caring. One does get the sense, though, that the kids would love it if this mediated representation of their crimes became somehow co-extensive with the actual events. They have finally become part of the Hollywood machine.

The tropes of Hollywood are used to an extraordinarily different effect in The Act of Killing (2012), directed by Joshua Oppenheimer with executive producers Werner Herzog and Errol Morris. In 1965, nearly a million citizens presumed to be communist sympathizers or simply inconvenient were massacred by death squads operating in alliance with the new regime. Today, Indonesia retains some alliance to this paramilitary history, and oftentimes those leaders of old are celebrated as heroes. The Act of Killing engages one of these men, Anwar Congo, in a reimagination of his role in the slaughter of hundreds of citizens. Over the course of the film, Congo and Oppenheimer re-enact some these killings in classic genre styles, such as the musical and the detective film. It seems remarkable that Oppenheimer was able to convince Congo to play along, until one considers that Congo has no shame. As the film’s website explains, “Unlike aging Nazis or Rwandan génocidaires, Anwar and his friends have not been forced by history to admit they participated in crimes against humanity. Instead, they have written their own triumphant history.” However, as the film progresses, real trauma is enacted by way of re-enactment: people cast to support Congo’s film projects are sickened and raise profound questions about what Congo’s pride means, and even Congo is forced into an uncomfortable (and totally insufficient) reckoning of his past actions. The creative licence of the genre films draws forth the pretense that there is an objective story to tell, which is never the case because nothing exists without context. The degree of abstraction, it seems, allows the façade of history to crack, forcing those involved to reconsider their understanding of what exactly happened.

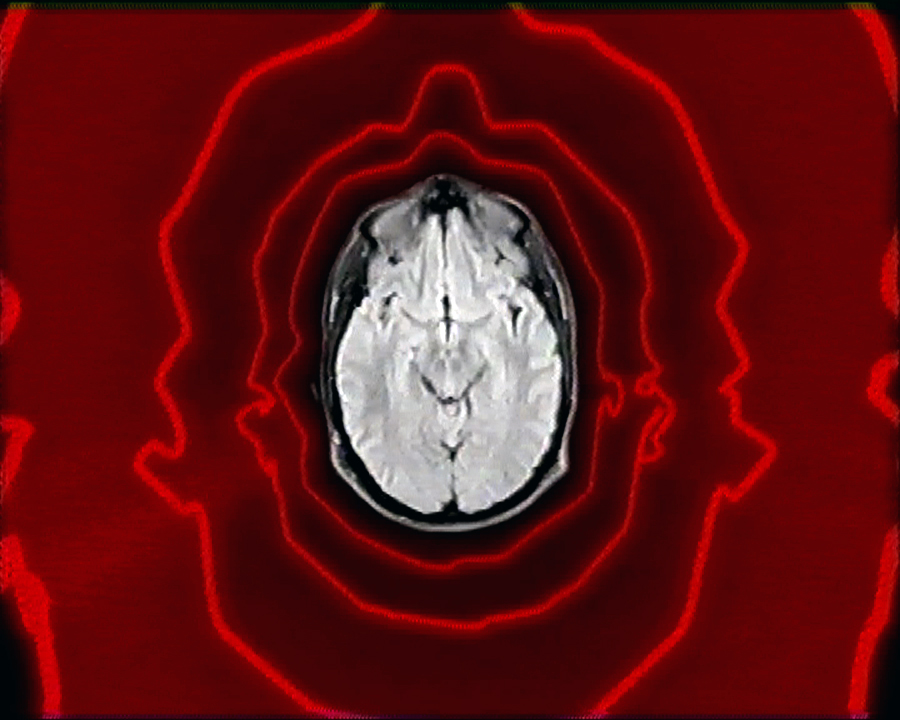

At a further degree of abstraction, Jeremy Shaw’s Introduction to the Memory Personality (2012/2013) is an installation work made in reference to the oeuvre of David Cronenberg, a director known for his role in defining the body-horror genre of film. Taking up broad themes around brain and body infiltration, the installation is composed of a padded cell capable of holding only a single person at a time. What unfolds feels like a real attempt to hypnotize the viewer, who is instructed to take a seat, the only seat in the room, upon entering. On the screen before the viewer, a mind-melting montage plays out. As images of the brain pulse and distort, a gentle voice makes a series of suggestions about the viewer’s conscious and subconscious minds. The story of Cronenberg’s filmmaking prowess is read through inspiration, through aura even, in the effect Shaw’s installation is able to provoke: a feeling of being unsure where one’s body begins and ends, literally. Shaw moves Cronenberg’s fascination with body horror from the screen and into our bodies.

It is by their nature that re-enactments are different from their referent, but they also generate their own realities. It is when these approximations of reality allow the ramifications of the real to be read in new ways that the re-enactment can be said to succeed. When the approximation is a blunt reiteration, then there is little to gain from the retelling.

Image courtesy of the artist.