I’ve heard that the music you are listening to when you are 25 will be the music you listen to for the rest of your life. I’m nearly a decade out from 25, and despite my impulse to rebel against the colloquialism, I can feel the ways I inhabit it, though from my perspective it is more that I am formed by music. Music saves my life but it is also my soundtrack; I cannot imagine my story without the sounds that have come to narrate it. What is falling in love or mourning, road trips or dinner parties, without that hum of music and the later possibility of pressing play and being transported back?

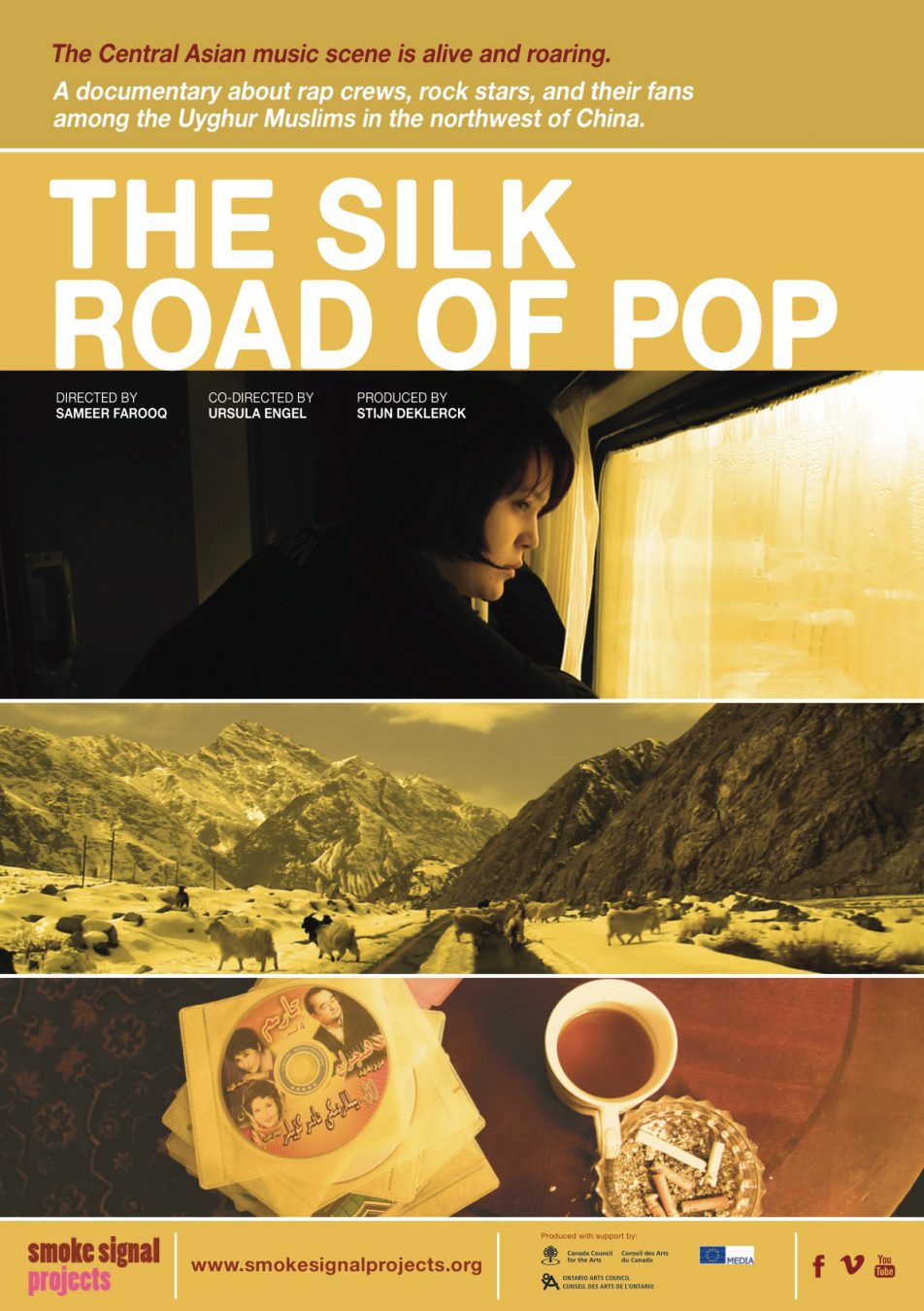

In The Silk Road of Pop (2013), a short documentary directed by Sameer Farooq with Ursula Engel, music is cast as life-blood, in this case for the Uyghur people, an ethnic minority based in the remote Xinjiang region of China. The title of the film is a reference to the Silk Road, an ancient trade route connecting remote interior provinces with far-away metropolitan centres along the sea, as well as linking China with its trading partners, including Xinjiang’s immediate neighbours Russia, Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. Today, the connections between Xinjiang and the rest of the country carries a wave of Han Chinese people to the province, going there to settle, or seeking work and less crowded living conditions. However, for the Uyghur people, this corresponds to an economic and cultural displacement, one addressed in part through music as a force for cultural expression and cohesion. The film follows Ay, a young Uyghur woman whose struggle to articulate her identity is shaped through the reflections that music provides. In modern Uyghur rock and roll, Ay’s cultural identity is acknowledged as a fusion of history and her own fierce independence. Although the bands she love may only have “100 fans”, this in no way diminishes the potency of recognizing oneself in cultural signifiers; if anything, it points to the absolute necessity of cultural expression as a means of cultural vitality.

At the heart of Cameron Crowe’s Almost Famous (2000), are Stillwater, a (fictitious) band on the brink of stardom, and William Miller, a thinly veiled surrogate for Crowe’s teenage self. At 11, William is bequeathed his older sister’s record collection with the premonition “Look under your bed; it will set you free”, and at 15 he is completely caught up in the rock and roll fervour of the early 1970s, writing reviews for a local underground newspaper. Given some twists of fate and some encouragement from the real-life character of Lester Bangs, the world’s great rock critic (in an incendiary performance by the late Philip Seymour Hoffman), William finds himself writing for Rolling Stone magazine. His first assignment is a think-piece on Stillwater, who are on tour, opening for Black Sabbath. Travelling with them across the country, William is befriended by the band, who endearingly call him “the enemy”, and by a group of Band-Aids, who might otherwise be known as groupies except that they are there for a love of music and not to sleep with rock stars. Stillwater’s struggle with impending success mirror William’s struggle with his own coming of age, but what they share is the simple love of music. Music is a beacon for both the band and William, the thing that can somehow address the cruelties of the world yet arrive in a place of hope. Crowe’s autobiography runs close to the surface of Almost Famous—he was a teenage writer for Rolling Stone and is still a music nerd—and the film reads as a love letter back to the time and circumstances that formed the director into the person he is today. Part of arriving is knowing from whence you came.

In 20,000 Days on Earth (2014), that point of departure is precisely measured in relation to the film’s subject: Nick Cave’s 20,000th day on earth, June 24, 2012. Portending to chronicle this 24-hour period (though it is more accurately a work of creative non-fiction and collage), filmmakers Jane Pollard and Iain Forsyth worked closely with the musician, author, and actor to craft a personal ode to the creative spirit as it inhabits one man. Despite Cave’s being known for his work with the Birthday Party and the Bad Seeds, 20,000 Days is not about music, but rather the force of creative labour—writing in particular—in shaping an understanding of the world. As Cave intones in the film, life certainly makes no sense when we are in it, only when we retell it. And retelling is the work of memory, a force both transformative and disastrous, a summation of what we are. As an artist, Cave exposes himself as cannibalizing his most intimate relationships, his songs a form of worship. This collected output becomes him, almost as the desired effect of the creative act itself. Through concert footage, staged scenes of everyday life, and a poignant interview with psychoanalyst Darian Leader, Cave’s life unravels as both moulded to the narrative he sets for it and inescapably touched by the hands of time, ticking ticking ticking. This is not an image of a rock star, but rather a man invested in a certain kind of creative translation. Before the ravages of time steal away his memory, which Cave admits is his greatest fear, there is this film, an attempt to capture the electricity that shapes his life, now and then.

A soundtrack is just one means of chronicling a life: a really good mix-tape bears much in common with a diary or a photo album. As it turns out, creative input and creative output are tied together in the formation of a self that always transcends these things, and yet cannot take shape without them. The music made me, but so did I make the stories, the images, the films.