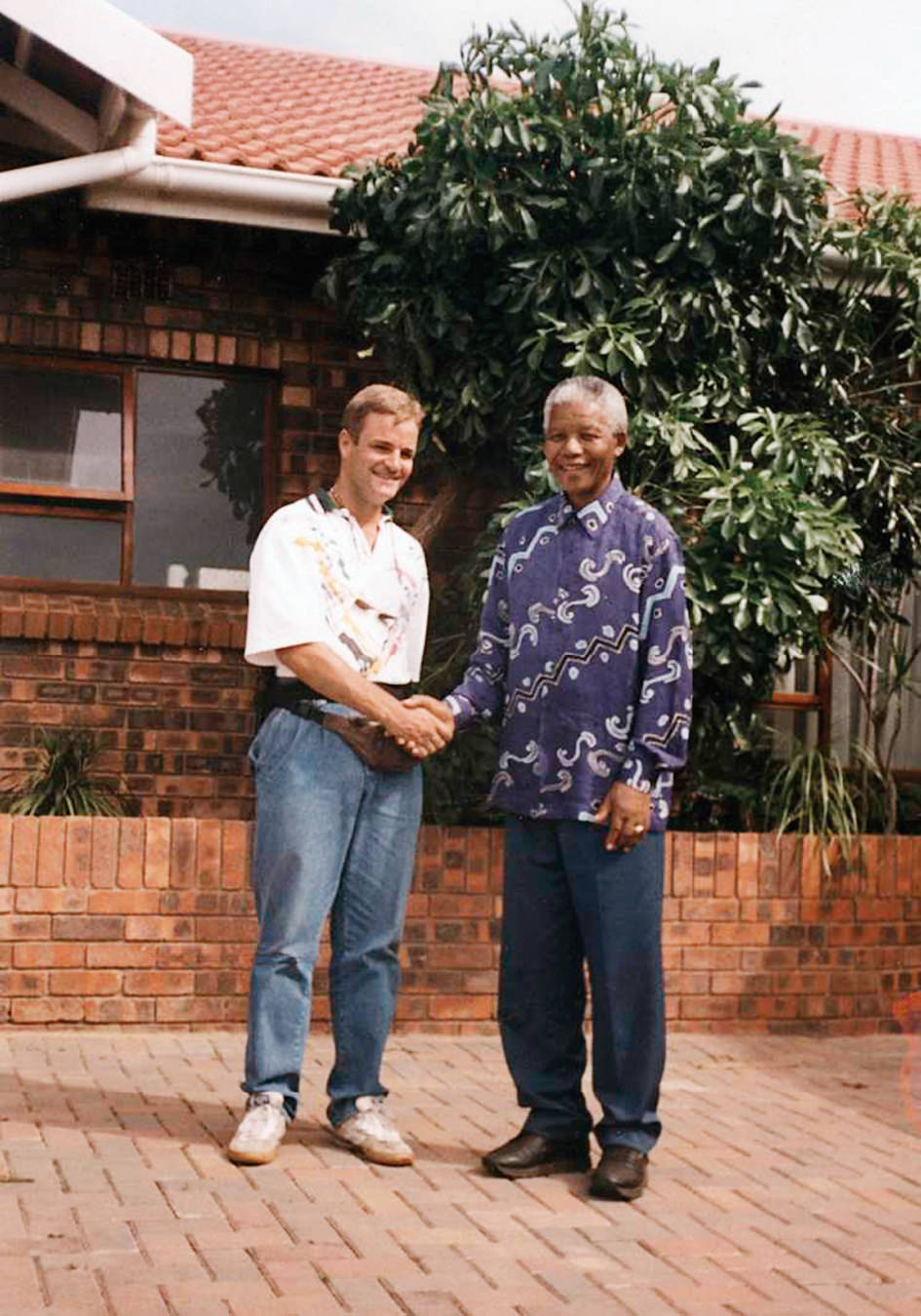

I remember where I was when Nelson Mandela died on December 5, 2013: at work, preparing for an important meeting. When I heard the news, I did not want to be at the office. In Vancouver, it was business as usual; halfway around the world, though, the Rainbow Nation started to grieve. When I left my downtown office and walked onto a dark Vancouver street, I suddenly felt a deep sense of loneliness and loss. Although Mandela was basically a stranger to me when I was assigned to guard him as a member of his security detail, a close bond based on trust and protection quickly developed between us. I worked with Mandela from May 1994 until February 1996, and on my last day with him, I told him he was like a grandfather to me; he leaned over, put his hand on my shoulder, and said, “You are my son.”

Heading home on a packed SeaBus, I wondered how many people sitting there with me had heard the news. How many of them knew what Mandela meant to South Africa? Later that evening I sat in silence, watching the images of an ever-growing crowd outside Mandela’s home. Many mourners were quietly paying their respects, appearing to inwardly reflect with their own personal thoughts. But I also saw the uplifting images of small groups of people clapping, singing, and smiling. In that moment, I more fully understood the meaning of celebrating someone’s life when they die. I felt I needed to go back to South Africa—where I was born and lived for 33 years before moving to Vancouver—to be there during that time of national grief. My decision was partly because of my respect for him, but mostly because of a gesture from him to me more than 13 years earlier. In May 2000, less than a year after immigrating to Canada, my wife passed away following a scuba-diving accident. I went back to South Africa for her memorial service, and while I was there, Mandela called me to express his condolences. He was no longer the president, yet he still took the time to call me. I wanted to go back as a show of appreciation for his kind, heartfelt words all those years earlier. I knew that, because of tight security, I would not make it to the actual funeral. However, I just wanted to be on South African soil, closer to Mandela.

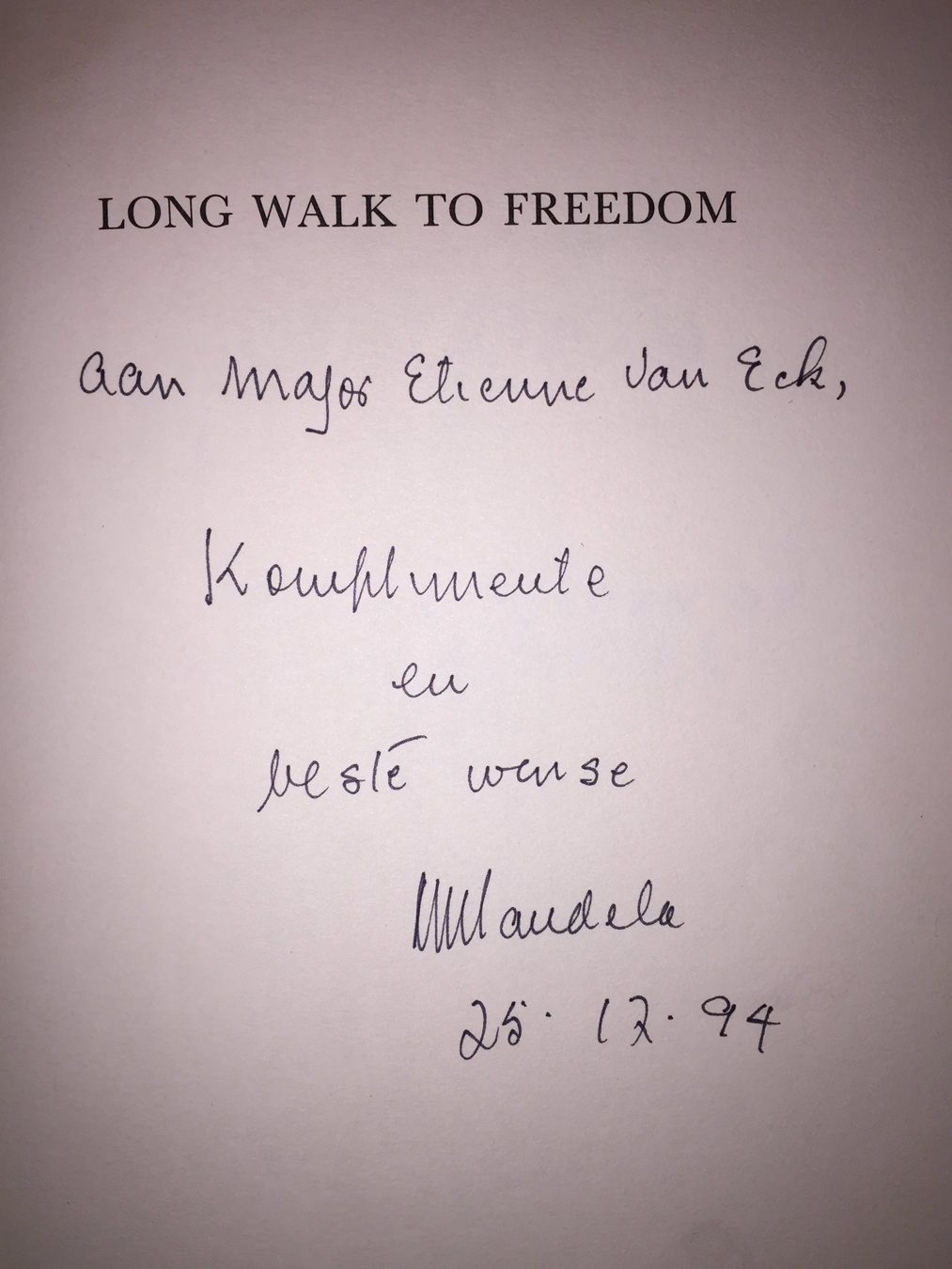

So on December 11, I boarded a plane to South Africa. That day I started reading Mandela’s autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom. I have a treasured copy of the book with a personal message from Mandela inscribed in it, which says, “Compliments and best wishes”. What makes the message special is that he acknowledged my rank—major at the time, even though I had come through the lower ranks while I was in the pre-democracy police force—that he wrote it in Afrikaans, and that it was signed on Christmas Day (1995). Mandela signed it while we were with him in Qunu, his childhood village. He always took the time to tell us that he appreciated the sacrifice we made in giving up our time with our loved ones to accompany him on trips around the world and to his village, sometimes for as long as three weeks, and sometimes over the festive season.

On one such trip, around Christmas Day, hundreds of local villagers were invited by Mandela to his home for a meal. Mandela had bought several sheep for the occasion, and some of the men proceeded to slaughter them and cook the meat on open fires. We bodyguards watched this all from a distance, some of us seeing something like this for the first time in our lives. Later we helped carry the meat to Mandela’s kitchen, and I noticed that it still looked a bit raw. When I walked into the kitchen, carrying a large plate stacked high with chunks of partly cooked meat, Mandela exclaimed, somewhat mischievously, “Ah, Etienne, you must have some meat!” He probably realized I was used to buying meat from a butcher and cooking it on a grill or in an oven. I felt obliged to accept his offer, and managed one or two mouthfuls before finding an excuse to go and check something outside.

I told him he was like a grandfather to me; he leaned over, put his hand on my shoulder, and said, “You are my son.”

Though I cherish my copy of Mandela’s book, I had never actually read it until that plane ride back home. I always used to joke, “I know the story, I don’t need to read it”; but in reality, I did not know the story. Over the coming days, I would get to know Mandela better, after his death. I landed in South Africa on December 13, the last day Mandela lay in state at the Union Buildings. I arrived at the buildings a few hours after landing, only to discover that I might not make it into the area where thousands of people were lining up to file by him. This was because only those arriving on buses from designated gathering zones were allowed into the area where I needed to be. Not knowing this arrangement, I had gone directly to the buildings. So I took advantage of the somewhat disorganized crowd control and tricked my way into the area, joining one of the lines of people. I remember thinking, “I’ve come this far—there’s no way I’m not going to say goodbye to my president.” Several hours later, I filed past Mandela. I promised him I would try to be more like him, and that I would tell as many people as possible about him. As I left the Union Buildings, I recalled his words: “Death is inevitable. When a man has done what he conceives to be his duty to his people and his country, he can rest in peace. I believe I have made that effort, and that is why I will sleep for eternity.” Mandela was buried on December 15. The following day was South Africa’s first day “without” him. It was also the Day of Reconciliation, and has been known as such since 1994, when Mandela became president.

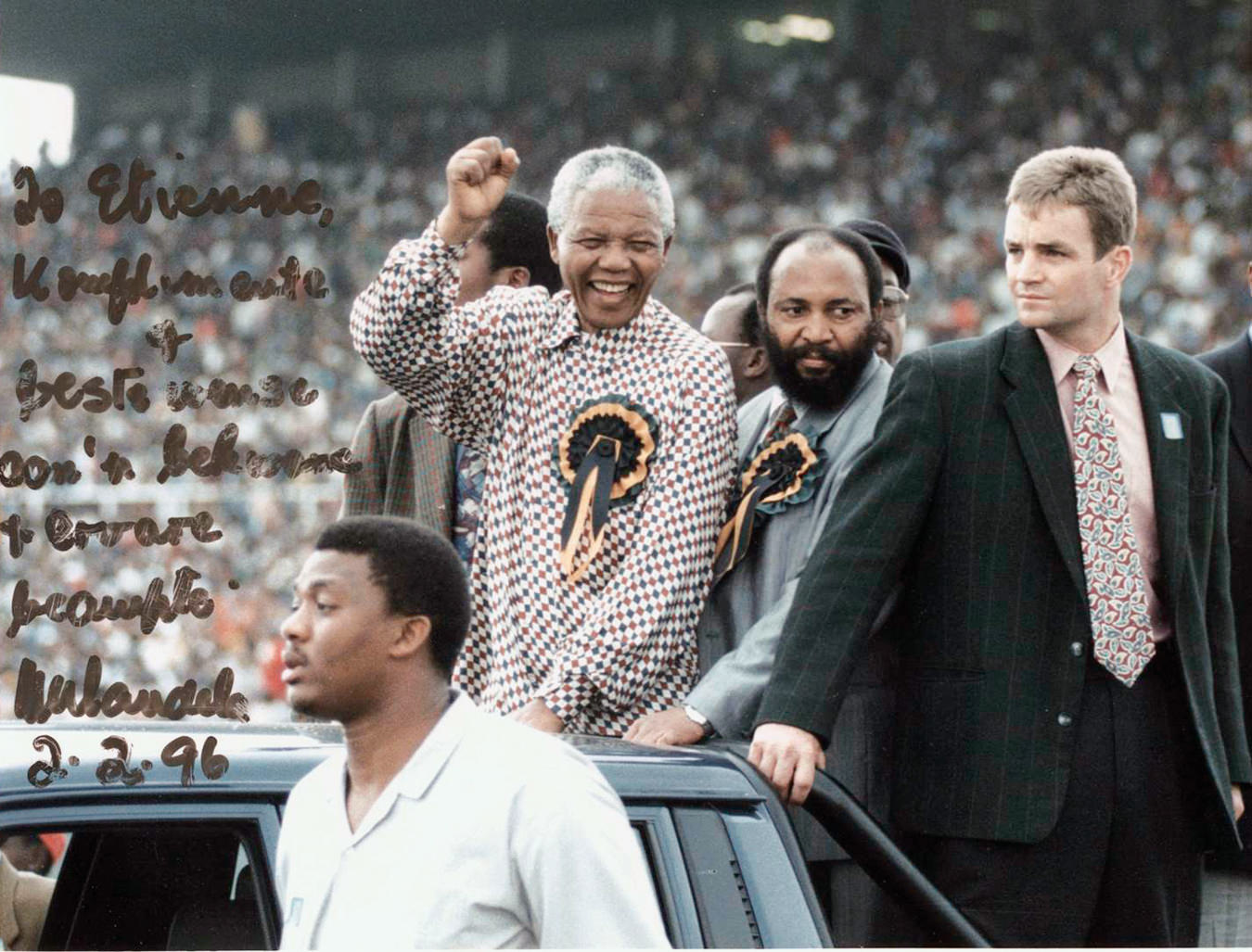

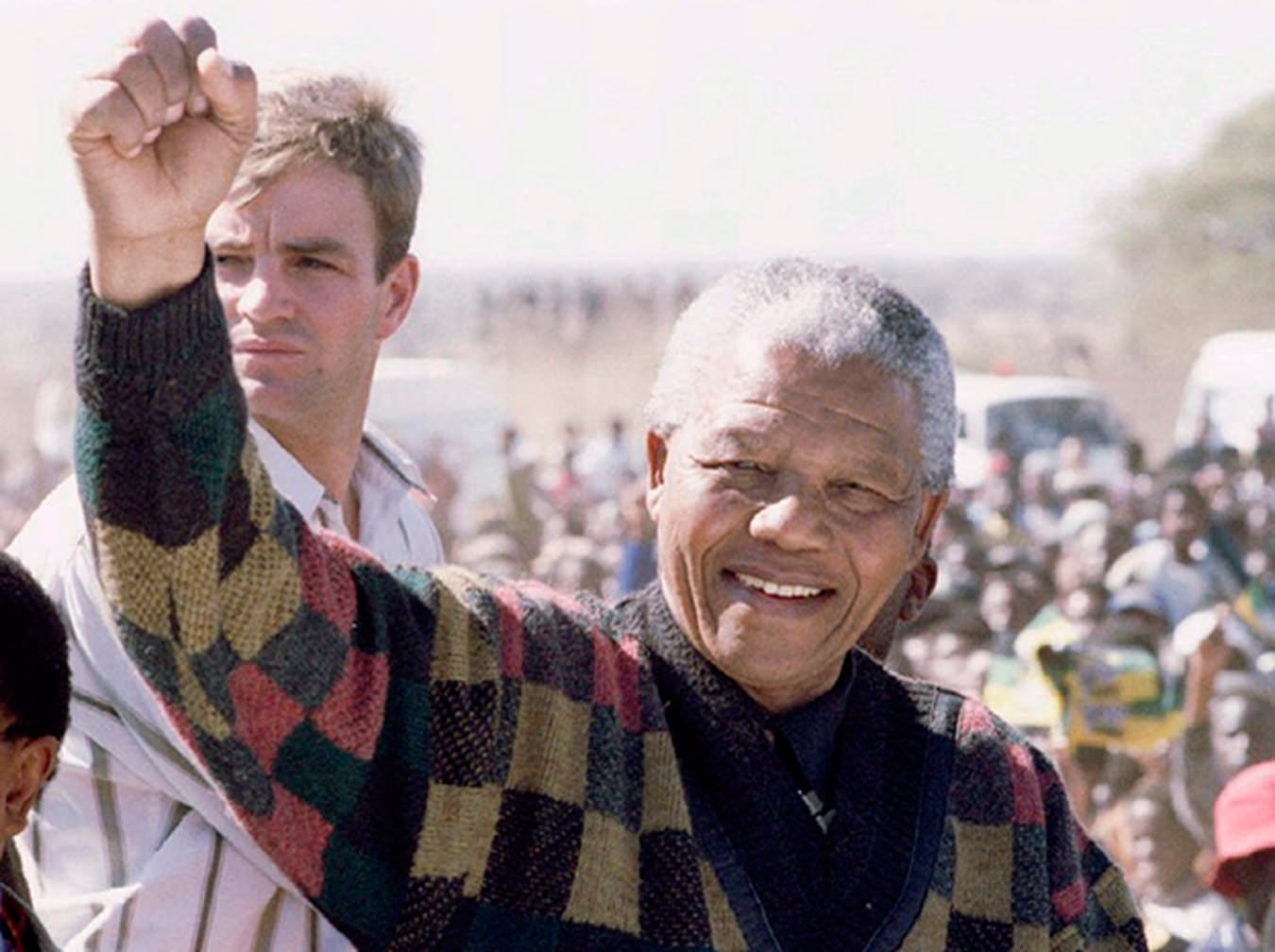

I awoke at 4:50 a.m., still jet-lagged. It was raining lightly and my thoughts drifted to Qunu, where he now rests. Mandela was a private person. Though I spent a lot of time with him, he never shared any stories about his childhood with me. Sometimes when we walked through the rural areas around his village, he would point to hills where he used to play, but he never shared any intimate recollections of his upbringing. He did, however, frequently ask me about mine. One of my most special trips with Mandela was when we visited my hometown together on an official visit, where he spent most of the day meeting local farmers and community leaders and addressing a stadium full of people at a public gathering.

Someone once said to me, “You walked beside a god.” I know what that person was trying to say, but it also made me realize, once more, what an exceptional person Mandela was. He was not a god; he was human. For me, he will never die. He chose not to concentrate on past grievances, but rather on reconciliation. He showed that through tolerance, patience, and understanding, you can change how people think and act. When Mandela called me all those years ago, he said, “You have the courage to turn tragedy into triumph.” And that is what this story is about: courage and triumph. That is how I remember Mandela.