It was the Summer of Snark. In Washington, D.C., dozens of National Building Museum visitors waded waist-deep into a “swimming pool” filled to the brim with pearlescent plastic balls. In Harbour City, Hong Kong, people tossed, rolled, and ricocheted off hundreds of white and silver bouncy balls swollen to 300 per cent of their size in an outdoor exhibit on the waterfront. And at the Metro Toronto Convention Centre, kitchen islands of undulating marble were crafted in collaboration with Caesarstone, each containing water in a different state: frozen into a giant orb; as steam curling from between the layers; or pooling over the tiered stone steps like a Hungarian bath.

“We’re constantly searching for ways to create spaces, environments, and objects that are engaging and have this kind of invitation for people to interact with them in a tactile way,” says Alex Mustonen of Snarkitecture, the New-York based collaborative studio he founded with Daniel Arsham in 2008 (Arsham is a contemporary artist, while Mustonen’s background is in architecture; a third partner, architect Ben Porto, joined the team in 2014). “Sometimes it’s more playful, sometimes that’s more meditative or reflective.”

Snark—a term used in 2018 to describe everything from presidential subtweets to Michelle Wolf’s biting standup—is actually in this case an homage to Lewis Carroll’s poem The Hunting of the Snark (the firm’s Instagram bio lifts a line from it: “The impossible voyage of an improbable crew to find an inconceivable creature”). Carroll’s work is one of the cornerstones of the “literary nonsense” genre, and Snarkitecture is a modern-day architectural equivalent. Each of its triple-take installations is fantastical in scale or detail, but at the same time, Snarkitecture’s clean lines and often-monochromatic palettes have made the studio one of fashion’s favourite collaborators. With 2018 marking its 10th year as a collective, Snarkitecture launched a book of 75 projects (categorized on a spectrum from “Not Art” to “Not Architecture”) that document a decade of its particular brand of sophisticated, maximalist absurdity.

“It’s this idea about making architecture perform in unexpected ways,” says Mustonen. “We are constantly questioning, ‘What is architecture? What is our relationship to it?’”

Photograph by Noah Kalina.

Snarkitecture has designed stores and installations for a variety of velar stops including Kith, COS, and Calvin Klein (for Kith, 200 all-white casts of Air Jordans dangle over hypebeasts’ heads in Los Angeles; for COS, glass marbles hum as they loop around four powder-blue metal tracks suspended from the ceiling in an exhibition space in Seoul, before plunking into an avalanche of white balls in an adjoining room). The trio’s latest partnership with quartz manufacturer Caesarstone—a company with a long-standing tradition of handing its goods over to experiential designers like Nendo, Jaime Hayon, and Tom Dixon—explores the concept of altered states: both the changing conditions of water, and the transformation of the utilitarian kitchen island into something decidedly, well, not useful. At least not in the traditional sense.

Backgrounded by the pulsing ambience of the Interior Design Show (IDS) in Toronto earlier this year—where the Caesarstone collaboration premiered, and was then adjusted for Vancouver’s own IDS—Mustonen hangs back from the small crowds that have formed around each of the amphitheatrical islands. People lean against the structures, hover their fingers in the steam; it’s almost unnerving to watch an IDS staff member press her palm into the perfect planet of ice at the centre of one of the islands, a handprint indentation sinking into the glassy surface.

“The idea was that the island is the centre of the home, the hub of the kitchen. It’s a space for gathering, it’s a space for eating, it’s a space for cooking, connection, et cetera, et cetera—but our starting point was actually to break those things apart,” says Mustonen, his expressive brows punctuating key words. His team learned that the Caesarstone material could handle extreme cold and extreme heat, and wanted to play with the solidity of the quartz sheets and the fluidity of water. “In this case, water and ice and steam were [an opportunity] to create things that were moving and in flux,” he says, gesturing to the ice island and the giant ball at its centre. “You can come back later in the day—the ice is going to be a different size.”

Because this is Snarkitecture and a project brief is but a springboard, there’s also a fourth outlier island: a fully functional, prehistoric-looking video game built into a countertop, with Caesarstone knobs framing a purposefully pixellated “PUSH TO START” screen. IDS visitors hover, iPhones at the ready, waiting for a parting of the crowds in the background.

Photograph by Noah Kalina.

In a time when toddlers and 20-somethings alike line up to swing on giant bananas and lie in a pool of rainbow “sprinkles” at the Ice Cream Museum (which was flooded by so many visitors, the Miami outpost was slapped with an environmental-hazard fine for the plastic capsules that littered the surrounding streets and storm drains), Snarkitecture’s grayscale pillow forts and ball-pit beaches (side note: the balls are antimicrobial and recyclable) feel more art than Insta-opportunism. But there’s the ever-present question: how much of what they create is for the experience, and how much is for the ‘gram?

“It’s something we definitely think about, and it’s something many of our clients ask for. But the work that we’re creating really doesn’t come from that place,” says Mustonen. Snarkitecture was founded pre-Instagram, after all, and the idea was simply to create physical experiences: “Tactile environments, things you could touch, things you could walk into and have this visceral connection with.”

Still, their projects are picturesque Instagram bait—something Mustonen first noticed at the entrance pavilion they created for Design Miami in 2012. Snarkitecture had rejigged the concept of a vinyl tent by inflating cylinders of the same material and hanging them vertically over the courtyard, creating an enormous textural, tubular awning. “What I was really struck by was all of these people doing this,” he says, miming that holding-up-a-smartphone stance, now ubiquitous enough to be the next silhouette on The Road to Homo Sapiens illustration. “As we became increasingly fixated on documenting our experiences,” he continues, “we saw a huge response to the environments we were making.”

Photograph by Noah Kalina.

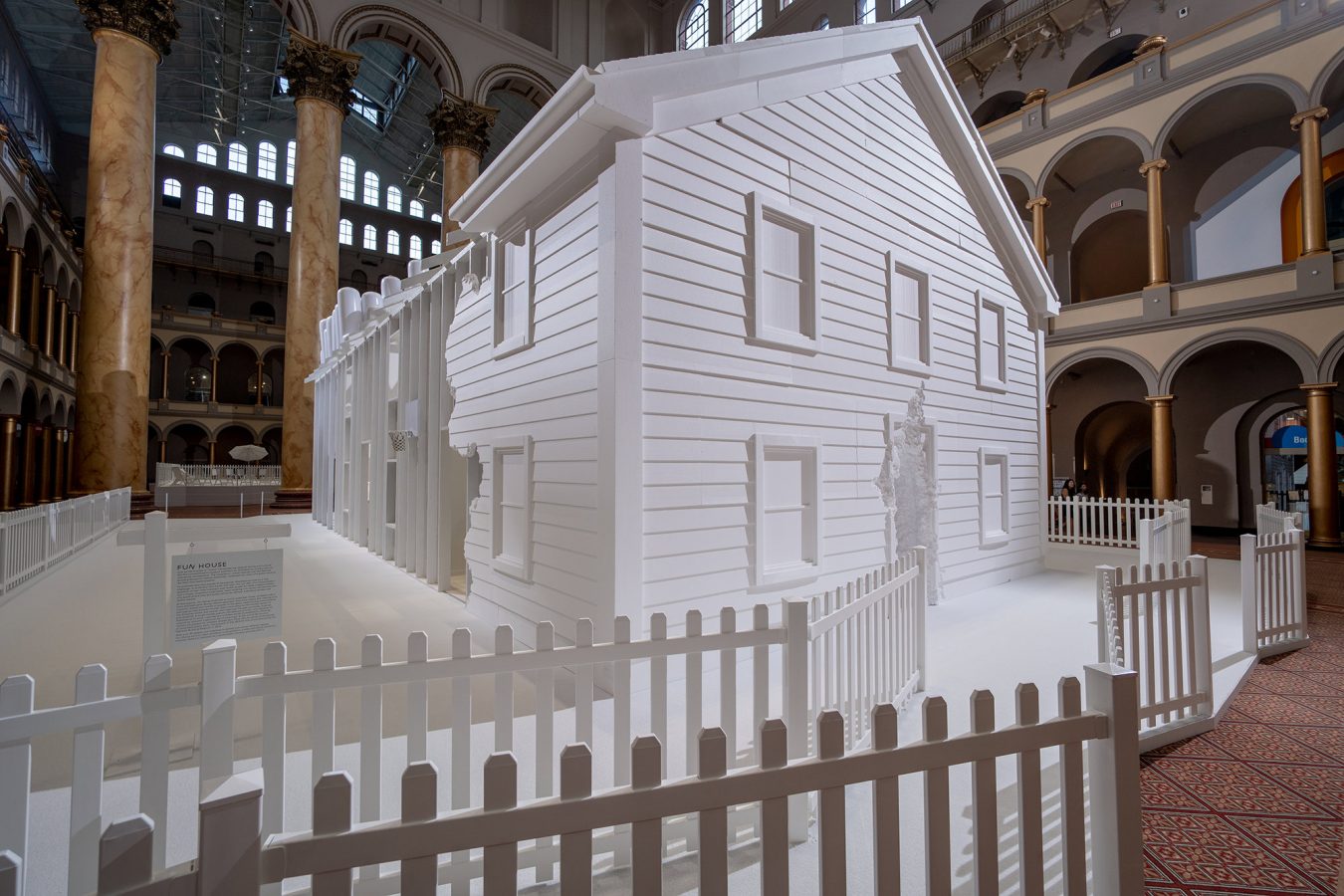

Snarkitecture’s “Fun House,” a summer retrospective celebrating its first decade of work and held at the National Building Museum in D.C., incorporated Easter eggs from projects past: a section of the inflatable canopy from Design Miami; a cluster of dangling Air Jordan casts from the Kith venture; and the aforementioned “swimming pool”—a smaller but no less selfie-friendly version of the world’s largest ball pit they had built at the same location in 2015. It’s cartoonish, all-white, and—wedged between the storied marble columns that once housed the United States Pension Bureau—the kind of thing that it’s hard to believe was actually approved in the first place.

“There’s this deep history of ‘paper architecture,’” says Mustonen, referring to architects designing dystopian or fantasy projects that were never meant to be built. “We respect that, and it’s an important part of the discipline. But we also knew we didn’t want to make a practice that just would only propose concepts. We wanted to propose concepts, but then invite people to experience them.” And experience they have.

Discover other inspirational Design stories.