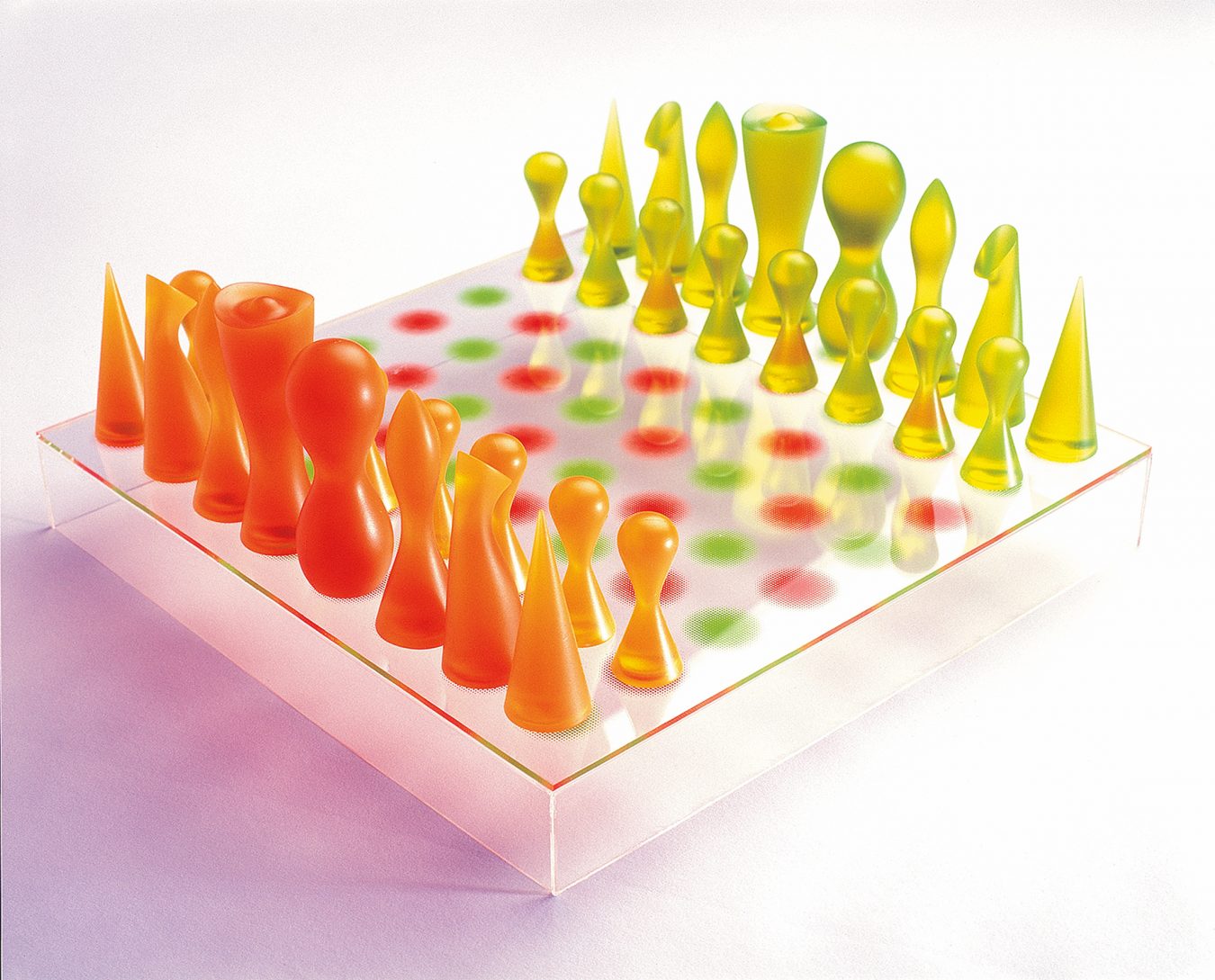

Karim Rashid loves white cubes, but he won’t be designing one anytime soon. “You can’t deny it’s not beautiful. I love modernism, I was brought up with it, and I was educated in a Bauhaus education,” says the New York-based creative, referring to his time spent studying industrial design at Carleton University in Ottawa. Even then, despite the school’s modernist pedagogy, Rashid gravitated towards organic shapes. “I remember wondering why we, as human beings, were so soft, and everything around us is so hard. We built a kind of hard world. We even built a Cartesian world, which I find amazing. We built grids for everything, right? And yet, a straight line doesn’t exist in nature. So it’s like we’re fighting nature.”

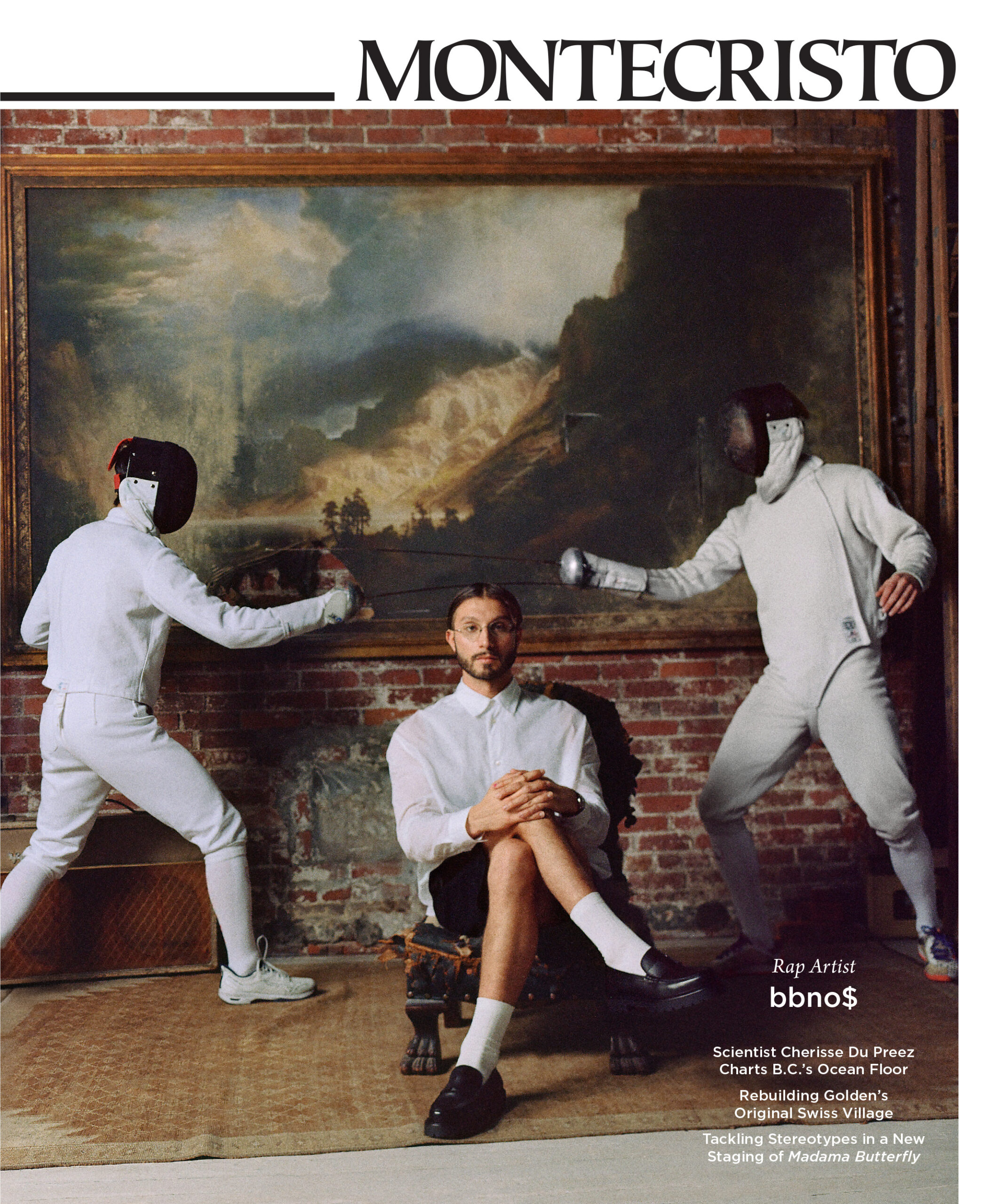

Over the last 30 years, Rashid has fought against this rigid Cartesian design. In a current aesthetic climate that favours monochromatic palettes and modernist minimalism, he gives us Technicolor and shapely organic blobs. “I lose a lot of work, and if I pulled back, I’d probably be much more successful,” he says. “But the reality is, I need to do that.” Even if he has scared a few potential clients with his designs, he has no shortage of work.

In January, along with being a special guest speaker at the 2018 Interior Design Show in Toronto, Rashid worked on 75 projects; in the last year, he has launched a hairdryer for Paul Mitchell, a line of seating for Matteograssi, and a luxury resort called Temptation Cancun in Mexico, just to name a few. With such an astounding number of projects on the go, it’s perhaps baffling that his team consists of only 17 people. “I’m a perfectionist, fastidious, controlling,” he claims, but that doesn’t slow him down. “The busier we are, we work faster, but we’re smarter. And our work’s better.”

When not travelling, Rashid sticks to a routine: he wakes around 6:30 a.m. and has an espresso before heading to the gym and then the office, where he meets with his team to review ongoing ventures. “Then I go back to my apartment and draw,” he says. By 5 p.m., he winds down with a glass of wine and maybe a film, but never an old one. Nostalgia is not on the menu. “I don’t want to be nostalgic about anything. I don’t listen to old music; I don’t want anything around me that gives me the creeps,” he explains. “It depresses me. I don’t want that. My work is very, very positive, and you know why? Because deep down, I’m very depressed. So it’s a way of dealing with existing. It’s a way of, let’s say, me staying alive.”

Rashid’s pursuit of positivity is evident in his work. His signature curvilinear forms, often in bright, happy colours, are what made him a household name, a rarity in the industrial design world. Part of that appeal is his eccentric nature, although the designer is much more subdued in person. Born in 1960 in Cairo to English and Egyptian parents, he moved to Canada at a young age and grew up in Toronto. After the completion of his studies at Carleton, he pursued a post-graduate degree in Naples, where he was taught by Ettore Sottsass.

“My work is very, very positive, and you know why? Because deep down, I’m very depressed. So it’s a way of dealing with existing. It’s a way of, let’s say, me staying alive.”

Although Rashid is not the nostalgic type, Sottsass holds a special place in his home: a 1983 lamp by the late designer is the oldest piece of furniture Rashid owns, a splurge from his student days. He was disappointed in last year’s retrospective on Sottsass at The Met Breuer in New York, as he felt there was not enough of a focus on the master himself. “I wanted to write a review, and then I thought, ‘If I write a review, maybe one day I might have a show there, I better not,’” he admits. At 58, he is ready for his own New York City retrospective. “I’ve had massive retrospectives. I just had a huge one in Seoul, Korea. Huge. I had a huge one in Munich. I had a huge one in São Paulo. Another in Milan.” Currently on display at the Ottawa Art Gallery is “Karim Rashid: Cultural Shaping”; running until February 2019, it is the first large-scale presentation of the designer’s work in Canada. “But I don’t have one in the States yet,” he continues. “The Americans don’t like me.”

He thinks his work is too “crazy” for America’s conservative tastes. It again comes back to nostalgia, something Rashid hopes to eliminate in design. “It’s known that in our 60,000 thoughts we have per minute, something like 80 to 90 per cent of them are about the past, on average. So I want to push that number down a little bit,” he explains. “We need to live in the present because that’s all we have. We don’t have the past: it’s gone. We don’t have the future, because we don’t know it. We just have now.” And it’s an exciting place to be.