For a woman wishing to become an architect, it was probably not a good idea to come of age in the 1920s. (It may not be a wholly good idea to come of age in the 2020s.) When Charlotte Perriand first approached Le Corbusier in 1927, he was already “one of the most revolutionary, controversial and vociferously influential architects and city planners in the world,” as The New Yorker would put it two decades later, and about as big-hearted as that description would suggest. “We don’t embroider cushions here, Mademoiselle,” was his contemptuous response to Perriand. He changed his mind on seeing the shining curves of her Bar sous le toit (“Bar Under the Roof”) at the Salon d’Automne, but not his attitude. Still, Perriand, working in the field if not quite in the job that she wanted, wasn’t complaining.

Maybe she should have been. The extraordinary four-storey exhibition devoted to her at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris is the first time this gallery has given its entire huge, Frank Gehry–designed space over to a single designer. On view until February 2020, it is an exceptionally broad and multifaceted exploration of the many talents of this woman who advocated l’oeil en éventail (the wide-angled view). But it’s also startling how much more famous her collaborators are. Fernand Léger, Pablo Picasso, Alexander Calder, Joan Miró, and of course Le Corbusier are household names. Perriand, who devoted her talents to making those households in every way more beautiful and more livable, is not.

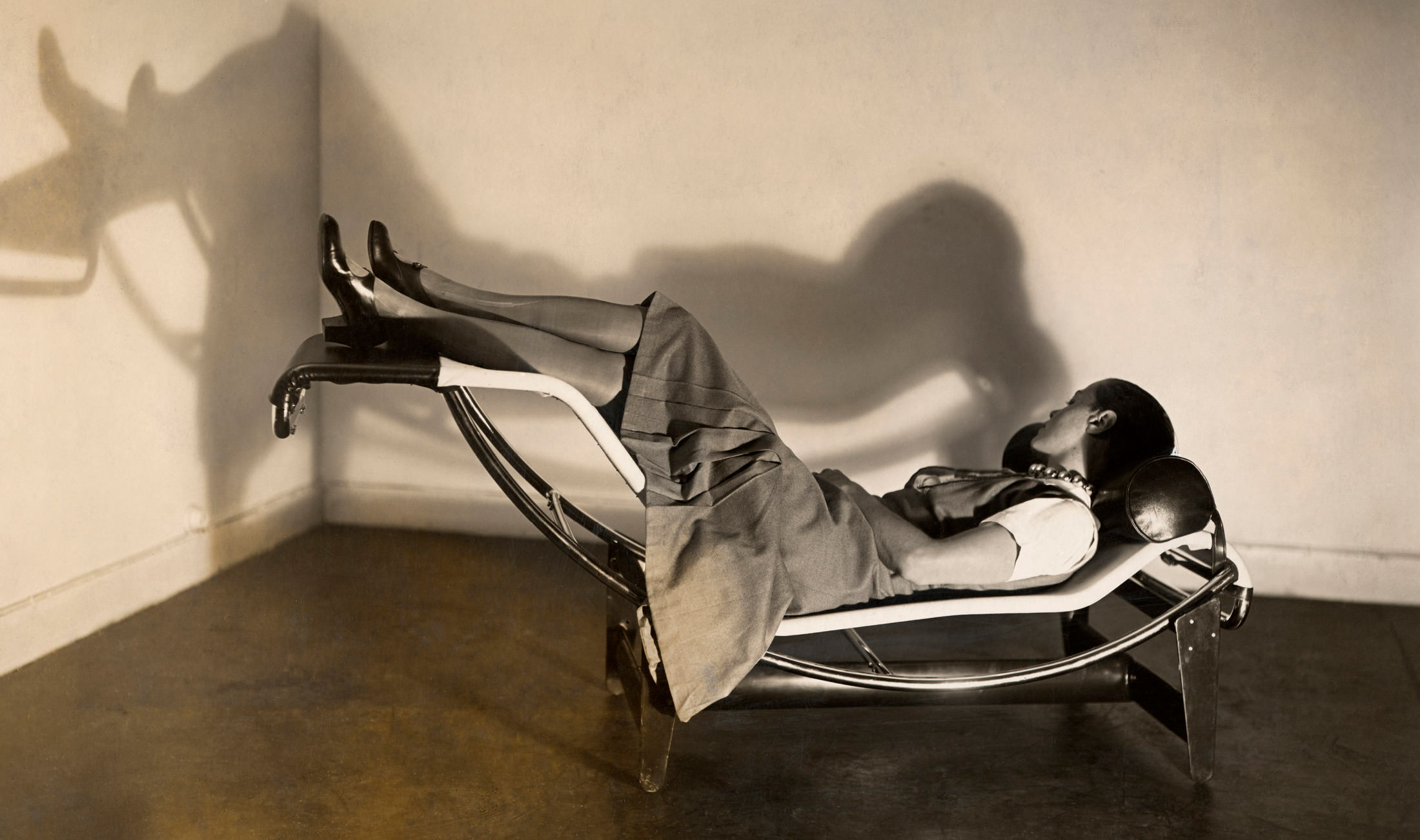

Charlotte Perriand. Courtesy of Fondation Louis Vuitton.

She was born in Paris in 1903 and died in 1999, and her life spanned the century in every sense. She spent 10 years as the Corbusier studio’s furniture designer, and it is a measure of what has not been achieved that her job description still, to us, has so much less gravitas than “architect.” Yet Perriand’s fauteuil grand confort (ultra-comfortable armchair) and adjustable chaise longue in steel and leather give shape and grace to Le Corbusier’s idea of design “from within to without.”

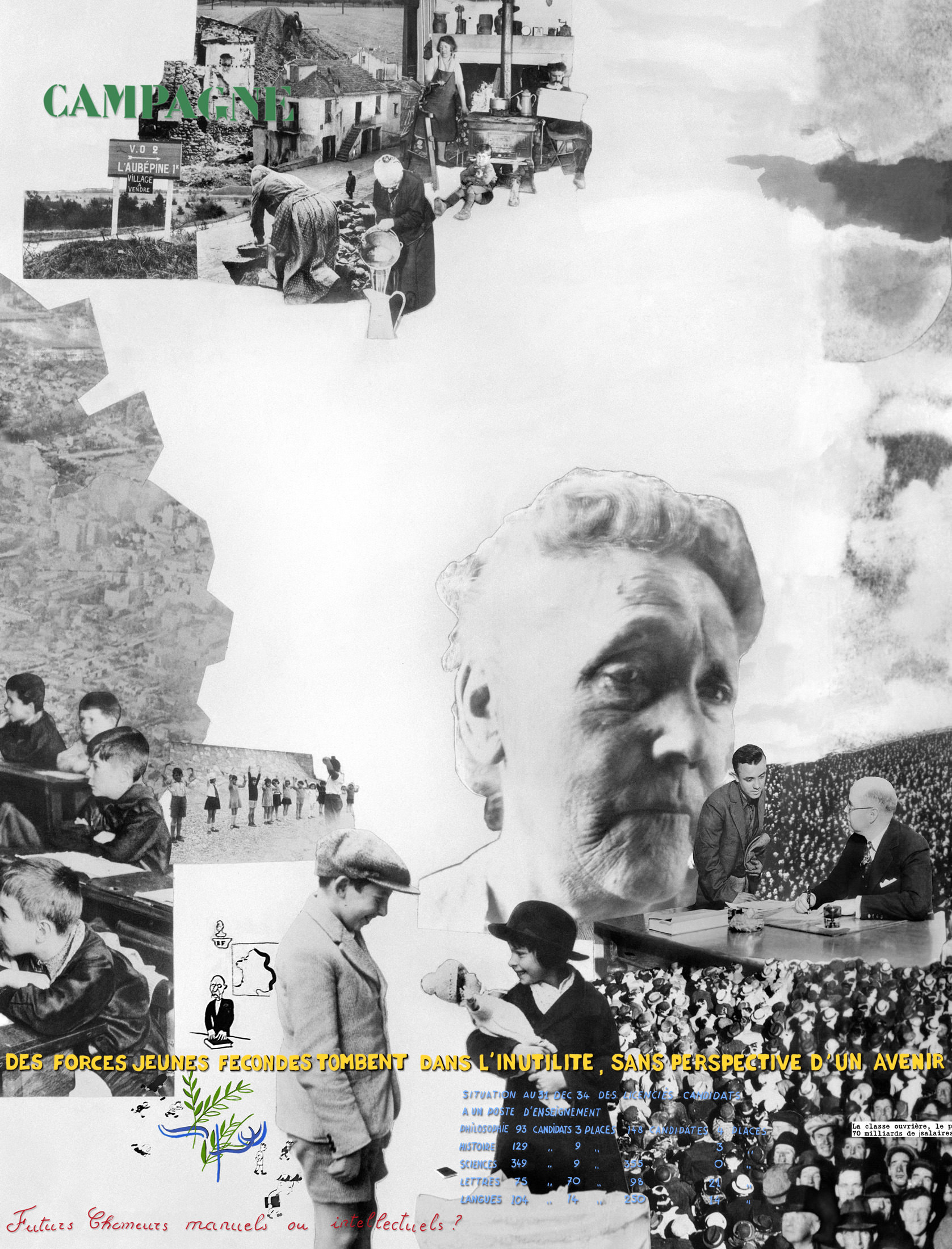

During this period, she also created gargantuan photocollages, with Léger and alone. These works, fiercely left-leaning adaptations of a collage technique only then recently invented by Georges Braque and Picasso, are revolutionary in every sense. To wander the length of her La Grande Misère de Paris (Paris, City of Poverty) is to be reminded that pollution and the exploitation of women were old news, even in 1936. She married, divorced, and had an affair with Le Corbusier’s cousin, Pierre Jeanneret. She and Léger collected “art brut”: stones, pieces of driftwood, any trifle that inspired them, and her brilliantly monochrome photographs of these are as surprising as the objects themselves are ordinary.

Detail from Charlotte Perriand’s La Grande Misère de Paris, 1936. Photo courtesy of Fondation Louis Vuitton.

In 1940, she went to Japan at the invitation of the Japanese Ministry of Trade and Industry to advise on increasing furniture exports. She curated an exhibition of her discoveries and recommendations in 1941 and was still there when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in December; after that, her position became increasingly uncomfortable, and she ended up in Indochina for the rest of the war.

This may have been personally unfortunate but artistically, it was marvellous. She studied Japanese forms and techniques. She recreated her famous reclining chaise longue in bamboo and oak (the steel had all been requisitioned) and designed a desk of lip-smacking desirability in the shape of a torii, or Japanese ceremonial gate. On a giant carpet, she reproduced a child’s drawing: a comment, explains the exhibition’s co-curator Olivier Michelon, on the infantilizing and dictatorial Japanese regime. She eventually returned from Indochina with a husband and a young daughter, Pernette, who now acts as guardian of her mother’s legacy.

The bedroom from the Maison de la Tunisie recreated for the exhibition on view until February 24, 2020. Courtesy of Fondation Louis Vuitton.

Perriand understood lines but did not think in boxes. She drew no distinction, in creative terms, between her furniture and the space around it, or between a work of art and a useful item that might incorporate it, nor did she collude in placing, or keeping, women in boxes of any kind: efficacy was as vital to her as beauty.

The kitchens she designed were always open, to ensure the cook (at that time, usually a woman) did not become a glorified domestic, stuck away from company. Nothing was sacred and nothing was trivial: she specified that her tables be the width of a grip (hers) between thumb and index finger, as an encouragement to caress them, and their slender, planed legs were modelled on airplane wings. She wore a ball-bearing necklace that she’d made herself, but her belief in the machine age was in no sense mechanical.

Charlotte Perriand’s 1955 design for a reception room. Courtesy of Fondation Louis Vuitton.

She lived freely, and that was not easy, particularly when recognition was less forthcoming than it should have been. “She leads a dog’s life as usual, with complications,” remarked Léger sadly—but Perriand refrained from sadness, bitterness, and all kinds of pettiness. Although Le Corbusier refused to take anything so offensive as the mother of a young child back into his business, she never expressed anything but admiration for him. It could be said she was the better man.

In the 1960s, she at last got her own chance to move from within to without, building a ski resort in southeastern France called Les Arcs that took prefabrication to new heights in every sense, with bathrooms and kitchens that could be dropped in place in the short summer season, before snowfall complicated construction. Her buildings shade into the hillside so that they disappear from above: another avant-garde idea that has become more common as ecotourism takes hold, without Perriand getting any credit.

Every object and space she created was in line with her desire to help make a better world. We aren’t there yet, but looking at this enormous, and enormously varied, exhibition, and seeing the care that has gone into preserving and recreating and explaining her work, it’s possible to believe that one day soon, we might.

Discover more in Design.