“Clothes,” wrote Virginia Woolf in Orlando, “are but a symbol of something hid beneath.” Cinema knows the power of this symbolism, and the film form’s symbiotic relationship with fashion—each form influencing the other; directors drawing inspiration from designers; individual films and characters developing style reputations quite separate from their artistic standing—might be construed as an ancillary, hybridized art form in itself.

From its earliest incarnation, cinema has used sartorial style both to draw the audience’s eye and to convey character information. In her 1997 book Undressing Cinema, Stella Bruzzi writes that clothes are “key elements in the construction of cinematic identities.” And those “identities” may refer not only to the characters embodied onscreen, but also the personae of directors and stars, to the atmosphere of a movie in its entirety, and even to the status and positioning of cinema itself.

The earliest Hollywood productions took an economical approach to screen attire, with costumes recycled for film after film, and performers such as Mary Pickford, Gloria Swanson, and Lillian Gish expected to provide their own dresses. Only as the pulling power of attractively outfitted stars became apparent did studios instigate their own wardrobe departments.

The bespoke creation of fabulous fashions fed Hollywood’s reputation as a hotbed of aspirational opulence, but also earned the attention of the high-end fashion world. Hollywood costumiers became famous in their own right; even Coco Chanel briefly relocated to Hollywood, though the fit proved to be a little off and her sojourn didn’t last. But ordinary women for whom haute couture was a distant dream also had routes to cinema-inspired glamour.

Joan Crawford in Letty Lynton (1932). Photo by George Hurrell/John Kobal Foundation/Getty Images.

As Michelle Tolini Filamore records in Hollywood Before Glamour, Macy’s department store in 1929 established in-house “cinema shops,” selling duplicates of outfits from the movies. “We have disseminated hundreds of Greta Garbos, Joan Crawfords and Irene Dunnes,” promised the publicity. “We can give almost anyone the cinema glamour.” And it was Crawford whose getup in 1932’s Letty Lynton—a ruffled white organdy number, inspired by Paris couture and designed by MGM’s legend-in-the-making Gilbert Adrian—created cinema’s first clearly identifiable fashion craze. Knock-offs swamped mainstream stores; tens of thousands of American women seized a Letty Lynton of their own.

“Paris may decree this and Paris may decree that,” declared Silver Screen magazine at the time, “but when that Crawford girl pops up in puffed sleeves, then it’s puffed sleeves for us before tea-time.”

In the near century since, the relationship between catwalk and screen has remained ambivalent; competitive; codependent. A gorgeously turned-out star, male or female, can be a forceful component of a movie’s appeal, and iconic onscreen looks have continued to cause high street crazes: think of Diane Keaton’s appropriation of menswear in Annie Hall; Tom Cruise’s Ray-Bans in Risky Business; or the Chanel Rouge Noir nail polish worn by Uma Thurman in Pulp Fiction.

Yet the values commonly associated with fashion as an industry—vanity, conspicuous consumption, sexual display—can clash with Hollywood’s conception of itself as a font of deeper wisdom. From the 1912 Mary Pickford vehicle The New York Hat to Amy Heckerling’s paean to 90s mall divas Clueless, movie characters who care too much about clothes tend to be headed towards some sort of ethical realignment. Comedies such as Prêt-à-Porter and Zoolander openly spoof vapid fashionistas and pretentious collection concepts; even in more solemn films, being beautifully dressed is as likely to be a sign of questionable character as of aspirational attractiveness. Tom Ford is hardly averse to luxury, yet in his film Nocturnal Animals, expensive sleekness is a source of suspicion: Amy Adams plays a woman whose presentation is as flawless as her life is empty.

Amy Adams in Nocturnal Animals (2016). Photo by Merrick Morton/Universal

In Hollywood, we see a system that at once wants to sell us glamour and wag a finger at us for the moral flaw of liking it.

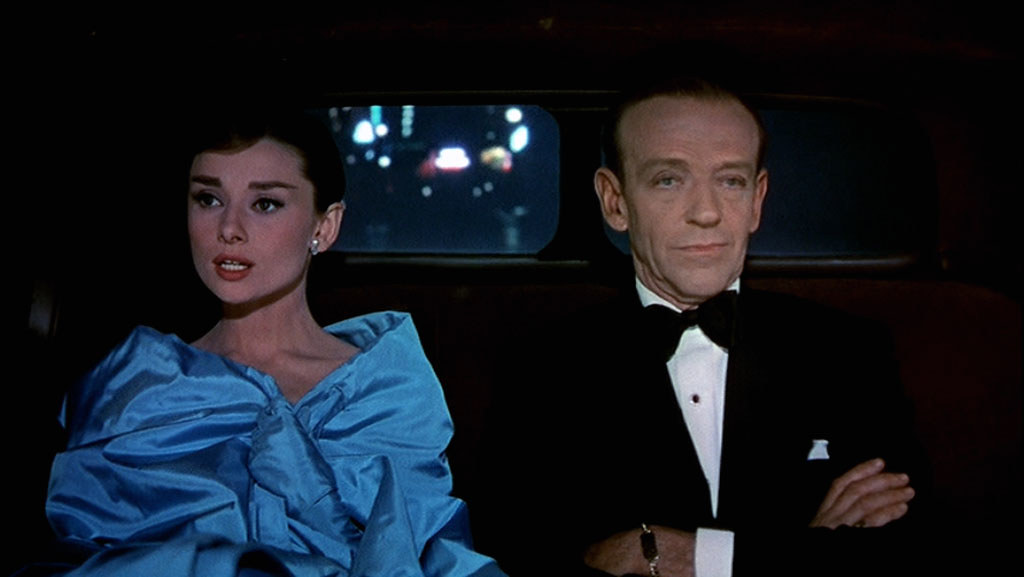

Both sides are played to particularly engaging effect in Stanley Donen’s Funny Face (1957), which sees Kay Thompson’s magazine editor and Fred Astaire’s high-fashion photographer find style inspiration in a woman defiantly unconcerned with fashion, Audrey Hepburn’s beatnik bookstore clerk Jo. The film is a balancing act between mockery and celebration of the rag trade: we’re invited to recognize Jo’s integrity, whilst recognizing the limitations of her assessment of fashion as “silly dresses on silly women.” Funny Face acknowledges that shallow materialism pervades the fashion world, but also makes the point that fashion needn’t be deemed morally inferior to any other media simply because its artworks are made to be worn.

Indeed, the influence of fashion upon cinema often takes the form of an injection of avant-garde edginess. When Michelangelo Antonioni investigated the dolly birds and shutterbugs of Swinging London in Blow-Up; when Peter Greenaway let Jean-Paul Gaultier colour-code The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover; when Nicolas Winding Refn turned horror haute in The Neon Demon; each time Wes Anderson crafted an expensively oddball look for one of his characters—pretentiousness or exclusivity might be credible charges, but hardly crass commercialism.

Randomness also has its role to play. What endures as elegant or beautiful, versus what looks ridiculous by the end-of-season sales, can be tough to predict, and films that invest heavily in their characters’ clothing can be barometers of bad ideas. Looks that went unappreciated at the time or were coded as “ugly” may be the ones that endure or get reclaimed.

Audrey Hepburn and Fred Astaire in Funny Face (1957). Screenshot from Paramount Pictures.

It’s an enjoyable irony of watching Funny Face now that the most fashion-forward look it offers is Jo’s pre-makeover wardrobe of flats, knee socks, ponytail, and beatnik black. Such shifts in the discourse, such reappraisals of what’s classy or cool or attractive, allow fashion and cinema to expand one another’s assumptions and coax each other out of comfort zones. Countless designers, including Marc Jacobs, Isaac Mizrahi, and John Galliano have acknowledged the style influence of “Little Edie” Beale, the heiress-turned-recluse who blazed through the 1975 documentary Grey Gardens in swimsuits, turbans, and capes. Raf Simons has repeatedly brought unlikely movie influences to the Calvin Klein catwalk, from Carrie’s bloody prom dress to the fishermen’s sweaters and beanies of Jaws to the mysteriously languishing housewife of Todd Haynes’ Safe. Gareth Pugh has drawn inspiration from Liliana Cavani’s deeply disturbing 1974 BDSM drama The Night Porter; Moschino has leaned on Mars Attacks!

When a film comes along that can lay simultaneous claim to mainstream appeal and a degree of political import, how it dresses its characters and how that look subsequently filters into fashion can be a matter of some significance. Part of the impact of Marvel’s mega-hit Black Panther was down to the way Ruth E. Carter’s costumes amalgamated superhero conventions with tribal traditions and warrior dress. The film’s 2018 release coincided with New York Fashion Week, and Marvel threw a “Welcome to Wakanda” catwalk show of designs inspired by its look.

Some styles, meanwhile, seem as improbably durable as vibranium, Wakanda’s mythical energy source. In 2017, Karl Lagerfeld closed Chanel’s couture show with a dress that paid explicit homage to the Letty Lynton, puffed sleeves and all. And the model who wore it? Lily-Rose Depp—a physical embodiment, as the daughter of Vanessa Paradis and Johnny Depp, of an exchange between film and fashion that never stops making new meanings.

Read more from our Style section.