It was 1989 when, by chance, I found myself going to my first powwow.

Although my heritage is Cree and Dene, I knew nothing of my own First Nations traditions growing up. I was one of those sad children taken away from my family, culture, and community in the Sixties Scoop.

Going to that powwow changed my life. Until then, I’d always been told that “Indians are dirty,” or “stupid,” or “lazy.” Words that caused me to be ashamed of my own brown skin. They were words that I heard every day when I was a child.

But even back then, there was always some type of presence, keeping watch, keeping me safe, and protecting me from harm. It resonated from the Earth, and whispered in the wind, telling me to keep walking strong. Promising that I would meet those teachers who’d help me find my way. Going to that powwow woke that up.

Called by the drum, I remember walking towards the dance arbour. I was speechless, realizing within seconds that everything I’d been told about my own people—my own culture—was nothing but lies. The dancers, the drummers, the Elders were all so proud to celebrate, so beautiful. Feeling overwhelmed, I started to cry. Tears of joy.

I needed to learn more. But where to turn? At the time, I didn’t personally know any First Nations people. I was still working for CBC Newsworld, back when it was based in Calgary.

Creator is good.

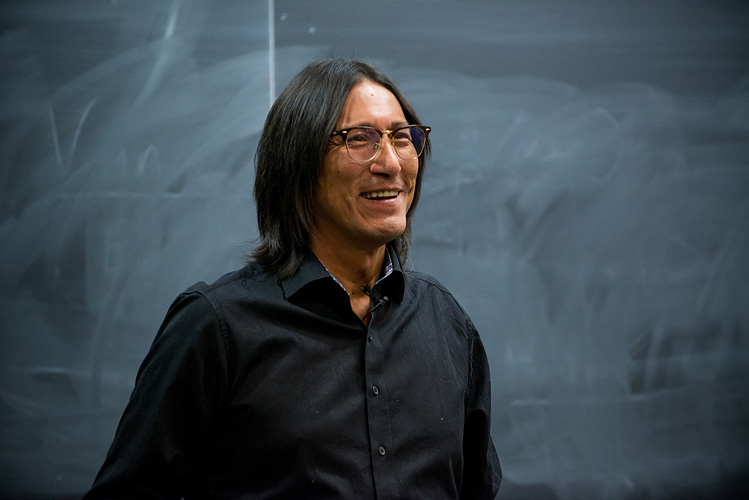

Calgary was where I first met Richard Wagamese. He was a columnist with the Calgary Herald at the time, and would sometimes visit the CBC studios as part of a political panel when Indigenous issues were being discussed.

If there is one word that describes Richard, it has to be “generous.” I give thanks for that.

Author Richard Wagamese in 2016. Photo by Queen’s University/Flickr Creative Commons.

After one of his panel discussions, I pulled Richard aside and introduced myself. I told him that I didn’t know anything about my Cree culture and needed to learn. “Where do I start?” I remember asking him.

Richard pulled out a pouch of tobacco from inside the leather jacket he was wearing. He handed it to me and said, “Bring this with you tonight. I am going to set up a meeting with an Elder I know. I’ll introduce you, and I am happy for you, Carol,” he said. “You are finding your way back to the circle.” Richard then explained that the tobacco was a gift I should offer to the Elder in exchange for advice and wisdom. And so my journey began.

With a gentle spirit. That is how Richard treated me. He was there when I met the Elder, who he’d befriended. Jack Kakakaway.

During that first meeting, Richard showed only patience towards me as I tentatively reached out to gather some smoke from the sage Jack had lit. I didn’t know what to expect, having been told all my life that spiritual practices of First Nations are sinful and pagan. I’d even been told that our beliefs were akin to worshipping the Devil. No exaggeration. Considering this, it’s little wonder that I felt uncomfortable the first time that I smudged with sage.

“This is how we pray,” Richard told me. “The smoke carries our prayers up to Creator.” Later, while walking me to my car, he talked about the significance of our four medicines used in ceremony. Sweetgrass. Sage. Tobacco. Cedar. He spoke with such reverence that I found myself feeling silly for having been uncomfortable at all. Richard talked about how, in reconnecting with his own Ojibway roots, he’d found strength and purpose in his life. He hoped I would find the same.

How blessed are we that he chose to share his knowledge, in spending time with him or through his writing.

I felt at ease in Richard’s company as he continued to prompt me to delve deeper into my learning. “The spirits are happy when we can address them in the old languages,” he’d say. It was then I first began to learn my own Cree language, through the free classes offered at the Plains Indian Cultural Survival School in Calgary at the time.

I can only remember him seeming to light up each time he saw me. He observed my growth as I continued to be a student and embraced my own culture. He’d tell me stories, about the first eagle feather he received and why he hung it prominently in his own home. “Each time I look at it,” he’d say, “I am reminded that we all come from a long line of strong men and women. I am grounded, and I feel content.”

It was shortly thereafter that Richard invited me to take part in my first sweat lodge ceremony. Again, at first, I was afraid. The lodge is small and dark inside. “Just breathe and offer gratitude. The Ancestors will know what’s in your heart.” And with that advice, my fear went away. I cried, again tears of joy, at knowing I’d been able to be a part of something ancient and strong.

This was my introduction to myself. Guided with prayer and a sense of belonging. Richard took me under his wing and never grew tired of answering the many questions I had. He was that way with everyone, which is why what he’s left behind with the posthumous publication of One Drum is a gift. With it, his voice continues to influence, forging a pathway towards inclusion, respect, and love. There continue to be many of us who seek peace and a sense of belonging.

Walk gently upon the Earth and do each other no harm.

It’s how Richard lived. It’s how he will always be remembered. Meegwetch, my friend. And thank you for sharing so freely, and continuing to lend your strength and your words.

Explore our Essay archive.