A bird stands with its feet facing forward while its long, slender neck twists looking back. Frozen in a moment of diametric movement, the bird occupies two spaces at once: it turns to the past while aiming toward the future. This is the symbol of Sankofa, an Akan word meaning “go back and get it” and a guiding principle of the Museum of Anthropology’s latest exhibition, Sankofa: African Routes, Canadian Roots.

The exhibition, which runs until late March, looks through the lenses of contemporary Black Canadian and African art toward traditional African art. One hundred items from MOA’s permanent African and African diasporic collection are displayed alongside 30 works from Black Canadian and African contemporaries. Viewed side-by-side, they reflect the enduring legacy of Black and African artistry; they are calls and echoes from Africa and the diaspora across time and space.

Sankofa “is this idea of having to go back to move forward,” Nya Lewis, founder of BlackArt Gastown and a joint curator of the exhibition, explains. Despite the word’s origin—the Akan language is spoken in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire—Sankofa, along with a range of other Akan symbols, has become a marker of cultural pan-African pride.

“In lieu of what was lost over transatlantic slavery, for African diasporic people to have something [culturally] specific to reach back to, there’s this idea of Sankofa being a philosophy that suggests, in all that you do, you have to look back to look forward,” Lewis continues. “We’ve used that lens to think about the museum’s collection and how it has interesting conversations with contemporary Black art and the experiences of Black Canadians right now.”

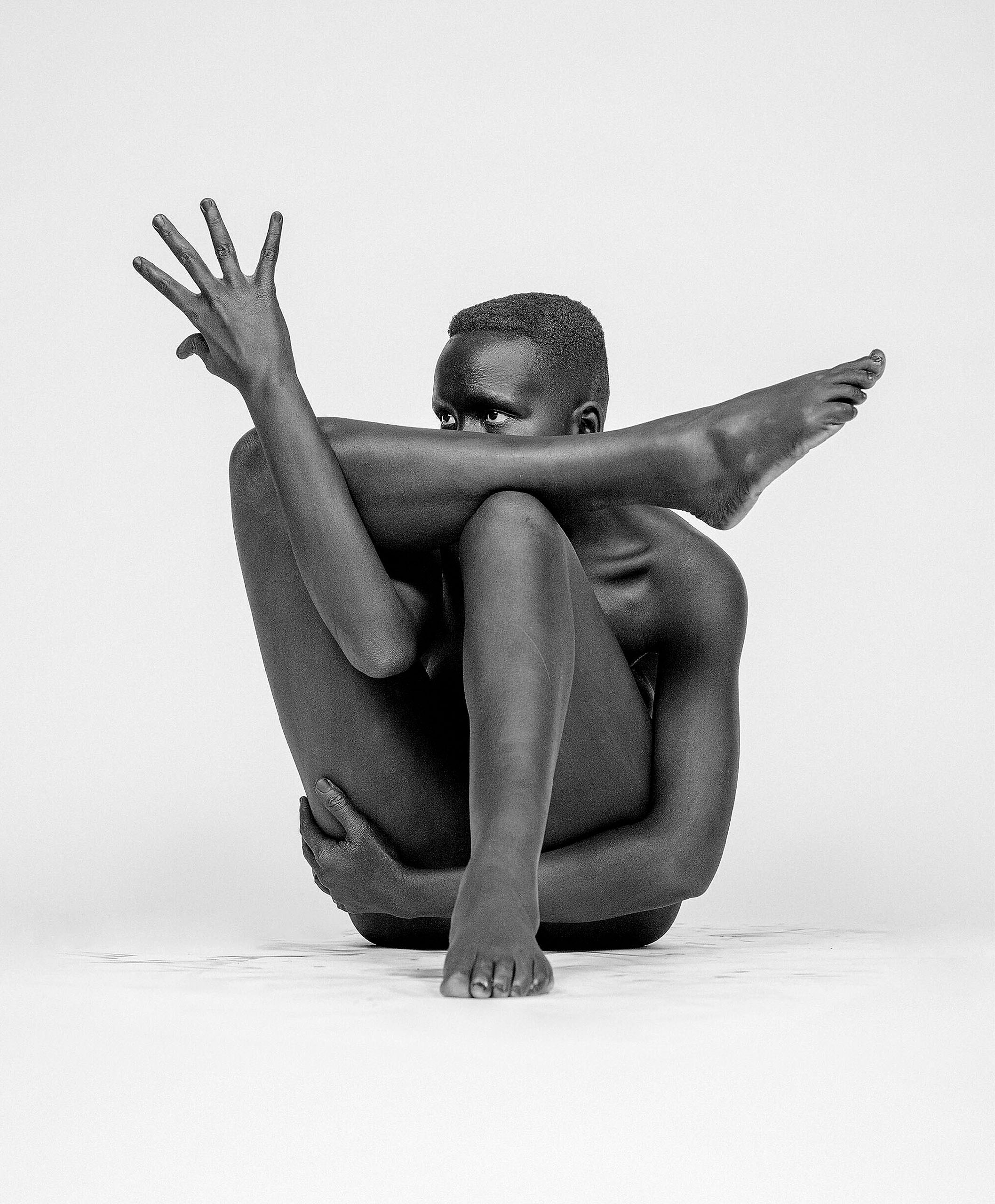

Bia Atôbe (Nya), by Michèle Bygodt (Vancouver), 2021.

A small wooden sculpture of the sankofa bird, taken from the museum’s collection and carved by an unrecorded Asante artist, opens the exhibition, setting the tone of reflection across time. Directly behind the bird, a vinyl-covered wall is printed with statistics and facts that Lewis chose to describe Black migration and presence in British Columbia. “African and Black persons are 38% of the victims of all race and ethnic crimes,” one reads. “African and Black youth are 3 times more likely to be suspended or expelled from schools than their non Black colleagues,” another says.

“What builds the level of connection between Black people that are living here and the things that we’re going to experience in this gallery? For me, it’s understanding that you can’t separate the people from the cultural production.”

“What builds the level of connection between Black people that are living here and the things that we’re going to experience in this gallery? For me, it’s understanding that you can’t separate the people from the cultural production,” Lewis says of the wall. “These are some of the untold truths that are less talked about.”

Centring the locality of Black Canadians—the “Canadian roots” of the exhibition’s title—was a main objective of Lewis and the curatorial team—Titilope Salami, a PhD candidate at UBC’s Department of Art History, Visual Art and Theory, and Nuno Porto, MOA’s curator for Africa and South America. “Black Canadians have been here even before Canada existed, and there is no acknowledgement whatsoever in education, in public discourse, about this fact,” Porto says, going on to explain how the slave trade in Canada and the continued erasure of Black presence are swept under the rug.

Lewis sees the exhibition, and its claim to Canadian roots and African routes, as a catalyst for conversation not only for non-Black viewers but for Black Vancouverites too. “I’ve gotten questions, mostly from Black communities, ‘What do you mean Canadian roots? There’s no Canadian roots in Black heritage; there’s only African roots and Canadian routes.’ And I think it’s an interesting conversation, the pushback from the Black community about acknowledging Africa as a route, because much of contemporary artistry is around middle passage or transatlantic slavery and trying to reclaim ourselves in that route,” she notes. “We live here, and we work here. This is where we’re putting down roots. This is where we’re attempting to reclaim ideas of what our African heritage looks like. So I think there will be lots of back and forth on that.”

Moving through the exhibition, past Lewis’ vinyl wall, viewers are presented with contemporary works from Vancouver-based Black artists including Michèle Bygodt, Chantal Gibson, and Odera Igbokwe. Bygodt’s striking black-and-white photographic series Bia Atôbe “We Are” captures the beauty and oddity of Black queer bodies. The photos, which depict both close-up portraits and shots of contorted bodies, speak to self-preservation, Lewis explains. “How do we reposition or recentre Black queer stories?” she asks.

Ibeji Project, by Stephen Tayo (Nigeria), 2019.

Gibson’s 2017 piece Souvenir finds row upon row of black spray-painted teaspoons hanging on the gallery’s walls. From afar, they are uniform—apparently identical. All idiosyncrasies have been painted over and forgotten. The work, a comment on the violence of Black erasure, is carried by the same ethos as the exhibition itself: a resistance against the monolithic narrative placed upon people of African descent.

Selecting from the museum’s permanent collection, the curators present an Africa that is a departure from depictions traditionally found in museum settings: the stereotypical primitive, the exotified subject, the “lingering coloniality of representation,” as Porto puts it.

In doing so, they thread visual narratives of a culturally rich continent that is connected throughout the world to vibrant diasporas. Igbokwe’s 2021 oil painting The Ori—The Connector is a celestial portrayal of an orisha, a spirit of cultural significance for the Yoruba people. Adjacent to the work hang several paintings from the museum’s permanent collection of Afro-Cuban orishas: a Santería version of the Yoruba spirit. Placed side by side, these works, both styles by a Yoruba diaspora, explore the infinite reaches of Black possibility.

And it’s that infinite nature that Lewis claims makes this exhibition only one fragmented part of the story. “We’re just showing what’s possible, and we hope that people do many, many iterations of this show,” she says. “There is so much untold history that we could never do it justice in this 5,000 square feet in this one go.”

At the end of the exhibition, the words “Black history is the impossible possibility” are plastered across a white wall. An open-ended goodbye, an invitation to keep digging.

“Our history is ongoing,” Lewis says. “We’re still writing it, still uncovering it.”

Bia Atôbe (Nya) Photo Courtesy of the Artist. Ibeji Project Photo Courtesy of the Artist. Read more from the Winter 2021 issue.