Michael Audain contemplates a self-portrait by Diego Rivera, the famed Mexican muralist, in a quiet corner of his expansive West Vancouver home. A news item about the painting’s 2009 Christie’s auction said the artist depicted himself “with unflinching realism and a mature self-consciousness.” Rivera looks well fed, and in the shadows a little on the olive side. Audain quotes Rivera’s wife, painter Frida Kahlo: “She said he painted himself as the frog that he is.”

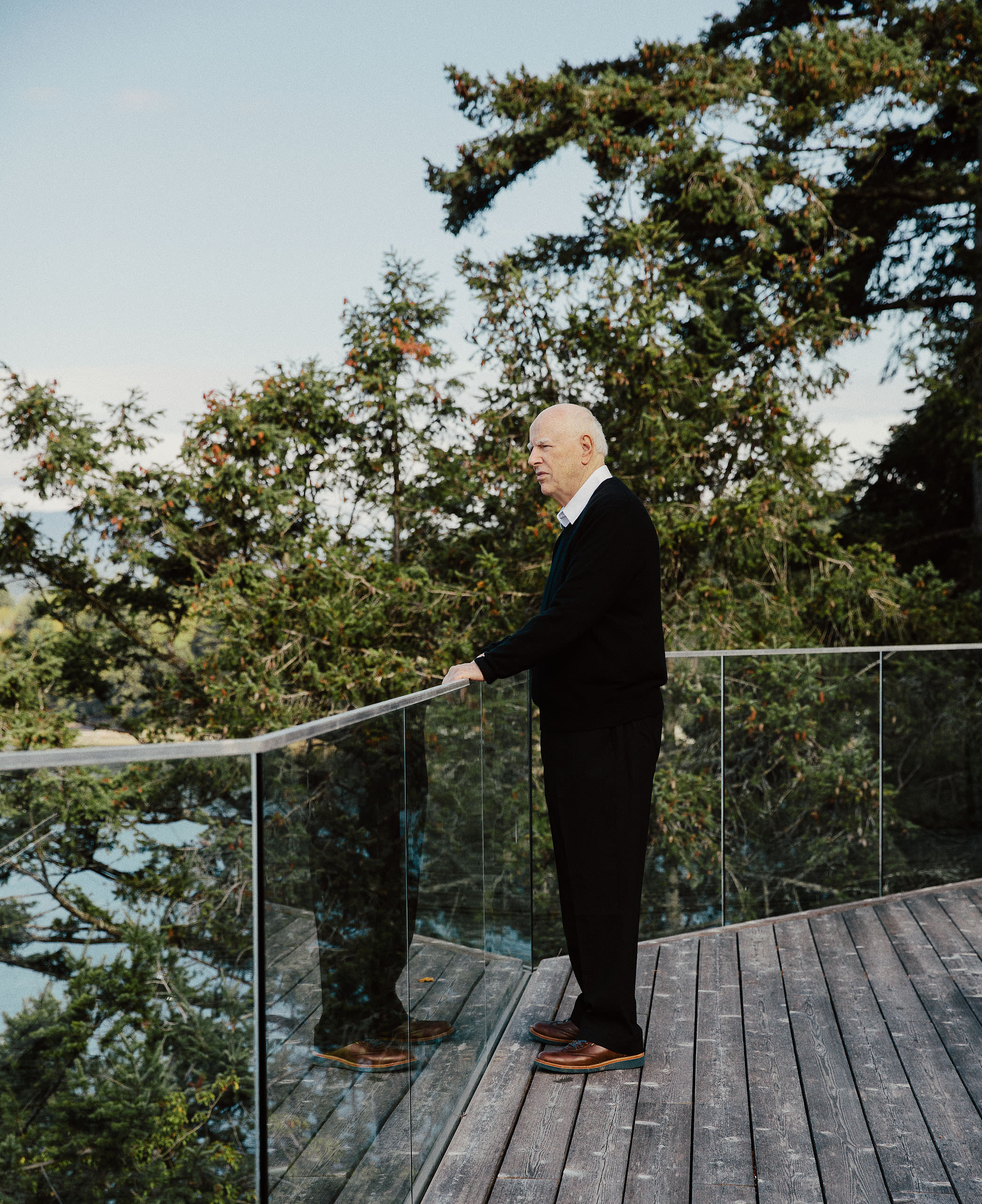

At 84, Audain has also been taking stock of himself with unflinching maturity, in a memoir titled One Man in His Time. The preface begins with a story from an Icelandic guide about why so many Icelanders write books. “They usually say it’s for their grandchildren, but I also believe it helps people to understand themselves better,” the guide told Audain. For himself, Audain says writing his book was an ordeal—he often maintains he’d rather look forward than back. But it’s over, he adds, and he’s okay now.

Audain’s life has its share of contradictions. He’s the descendent of an early B.C. captain of industry who became a boarding-school outcast in England. An admirer of Fidel Castro who became a wealthy private real estate developer. A child raised without art in his home who became one of art’s most devoted patrons. The book’s 59 anecdotal chapters show the threads of this cloth clearly enough.

The art story has a few, of course. The most recent was sewn in early November, when Audain made the single largest private cash gift to a gallery in Canadian history—$100 million toward a new $400-million Vancouver Art Gallery, with a design reimagined in close consultation with local Indigenous artists. One of the earliest threads was woven in place in 1951, when Audain met Kwakwaka’wakw master carver Mungo Martin, who was working on a totem pole in Thunderbird Park, across the street from the teenage Audain’s swimming lessons at Victoria’s Crystal Garden pool. Audain asked about a figure Martin was carving: was it a human face or a bear? “It could be a bear becoming a man, or perhaps a man becoming a bear,” Martin said, and explained Indigenous mythology to the inquisitive young man. Audain’s curiosity had already been kindled by Saturday morning classes for children at the Royal BC Museum. Absorbing Emily Carr’s brooding forests sometimes gave way to handling Indigenous artifacts with white cotton gloves.

For an even younger Michael Audain—the child of a broken marriage, evacuated from the Channel Islands on a British destroyer; the young boy who fled the London Blitz for the English countryside and then boarding school—British Columbia was just a romantic faraway place, his family a distant past. Great-great-grandfather Robert Dunsmuir was a Vancouver Island coal baron. His son James, who became premier in 1900, married his eight adult daughters to “men who were attractive, high-born and relatively useless,” according to a Dunsmuir biographer. His grandmother Sara Dunsmuir married Colonel Guy Audain, who resigned his commission in India for safaris on a family pension. By the time of his own arrival in 1937, Audain writes, his family had “reduced the dynasty to a smoking ruin.”

Michael’s father, Jimmy Audain, led an alcoholic army officer’s peripatetic life in England and Ireland through the Second World War. He worried that his “sissy boy” son would not succeed in a respectable profession, the most desirable being a life in the military. In the book, there’s a photo of Michael looking insecure in boys-school short pants and cap. The caption notes that he “did not distinguish himself academically, or on the sporting field.” Jimmy sometimes expressed his disappointment with a swat from a belt.

In 1947, Jimmy brought his family home to Vancouver Island. At Burrard Inlet’s old CPR Pier B-C, they boarded the Princess Victoria—a Canadian Pacific steamship depicted in an E. J. Hughes painting that Audain now owns—for the last leg of the journey. It was, Audain once said, “the most important day of my life.” By the time his teens were over, he had found worlds of culture and nature far different from stratified postwar England and was on a Greyhound bus to Mexico to see the socialist murals of Diego Rivera. Did art become life? Did a man become a bear? Regardless, Michael Audain’s life had taken a turn.

As a University of British Columbia student in 1961, Audain went to Memphis to learn about housing policy. At the time, young Christians and student radicals were challenging the South’s segregation laws. On a bus trip to New Orleans, he ordered a meal at a Blacks-only lunch counter in Jackson and for his trouble was sentenced to four months in jail, part of it spent in Mississippi State Penitentiary. At the founding convention of the NDP that same year, then-leadership contender Tommy Douglas gently persuaded Audain to remove a photo of Fidel Castro from a booth on the convention floor. Since January 1, 1962, Audain has exclusively worn black neckties as a protest against nuclear weapons. Today he notes that ties are no longer de rigueur. “I was surprised to hear that certain bankers felt they should don a tie when calling on me!”

He worked as a social worker, a prison guard, a civil liberties advocate, an agricultural economist, a would-be pilot working in the North for Canadian Pacific Air Lines, and most importantly, as a housing policy analyst.

All of which leads to the second sharp turn in Michael Audain’s life, one that didn’t play out until he was in his forties. Audain was certainly busy before he got rich. In 1962, he married his first wife, Tunya Swetleshnoff, with whom he had two children. He worked as a social worker, a prison guard, a civil liberties advocate, an agricultural economist, a would-be pilot working in the North for Canadian Pacific Air Lines, and most importantly, as a housing policy analyst. Audain advised governments, taught at UBC, shaped cooperative housing policies, and helped expand the B.C. government’s role in building housing. Yet in 1980, he was invited to become a partner in a new private housing development company.

“It was a great surprise to me to find myself actually building housing,” Audain says over tea, while his wife, Yoshiko Karasawa, takes the family’s Labradors for a walk. “How does a left-wing activist become a real estate developer? Most of my life, the cards have been dealt. If I’d gotten involved in real estate in Regina, I wouldn’t be sitting here.”

Karasawa, too, marked a midlife turn. In 1981, a Thai Buddhist monk told Audain, “You will marry an Asian lady.” He soon found himself charmed by the talkative energy of a Japanese hairdresser in a Seymour Street salon, and their shared love of art has since made them great collaborators.

There were also roads not taken. In 1974, encouraged by Dave Barrett, then-premier of B.C., Audain ran for the federal NDP nomination in Vancouver Kingsway but lost. “If that had happened, I would likely have had a political career.” When the offer came to build private housing, he had planned to write a historical novel set in Thailand.

Real estate is not an easy place to build an enviable reputation. For a while, Audain was “one of B.C.’s most notorious builders of leaky rotten condos,” in the words of one critic. More recently Polygon has been criticized for displacing poor people near Metrotown. Developers are often regarded as mere profiteers. Audain says he has simple goals. “My business is about creating housing for people. We want to achieve a certain price point, or a certain rent. It has to be affordable.” He figures his companies have built about 30,000 homes worth $30 billion, almost all in the Lower Mainland. Today, Polygon is widely seen in the industry as an influential fair dealer and a careful, cost-conscious operator.

Housing, however, is hardly the only thing Audain builds. On November 4, he stood in the atrium of the current VAG, located in a century-old former courthouse, to announce his family foundation’s gift to fund a new gallery building. Beside him stood a rendering of a copper-coloured facade, recast with Indigenous weaving in mind. Musqueam weaver Debra Sparrow spoke about how much it meant that the gallery’s new CEO and director, Anthony Kiendl, brought local Indigenous artists into the process to help create a building in downtown Vancouver that reflects both ancient and modern cultures in this place.

Vancouverites haven’t always welcomed proposals for a new gallery. They see a lovely old building in the heart of the city, with some notable exhibits, and wonder what the problem is. Audain, in his living room, is blunt: “The building is actually a disgrace. The spaces are not large enough to allow for an exhibition of the best art of our province. It cannot accommodate all the school groups. The VAG suffers from inadequate environmental controls, and the staff are working in areas that have not been seismically strengthened. It’s also where many Indigenous people were sentenced to long prison terms and even death. It’s really a colonial relic.”

Yet plans for change were dogged by controversy and rancour. Should the VAG excavate and expand below the existing site, repurpose the old downtown post office, create a series of satellite facilities, or build anew on a City of Vancouver–owned site next to the Queen Elizabeth Theatre? Long-time gallery director Kathleen Bartels pushed for a distinctive building by renowned Swiss firm Herzog & de Meuron, architects of the 2008 Beijing Olympics’ Bird’s Nest stadium, but the design was not popular or entirely functional, and when Bartels left the VAG two years ago, the proposal lost its fundraising momentum.

Now, Audain says, it’s time to move forward. He notes the last major piece of new public arts infrastructure built in downtown Vancouver was the Q. E. Theatre complex itself, in 1959. “It’s amazing to me.” He argues the Province should lead. “It should see itself as concerned about the artists of the province, and this hasn’t happened yet.” He also believes the VAG should consider recasting itself as a provincial institution. “In Halifax, Toronto, and Edmonton, civic galleries have become provincial galleries.” The provincial government was represented at the VAG announcement but did not deliver a cheque. The federal government was absent. Yet Audain and others are optimistic that they and other donors will provide the $160 million the project still needs to go ahead on the Larwill Park site provided by the City of Vancouver.

A stronger tradition of cultural philanthropy in B.C. is something Audain wishes for. “Here the main thing is universities and hospitals, and lately environmental causes,” which Audain supported by creating the Grizzly Bear Foundation. “Yet we have so many outstanding artists here, because of the tradition of art-making that goes back thousands of years on this coast, and because of the excellence of our art schools and university art departments.” He has championed them with an annual $100,000 Audain Prize. Winners have ranged from Musqueam artist Susan Point to internationally acclaimed Vancouver photographers Stan Douglas and Jeff Wall, and this year, Haida artist James Hart. “We need to know that we have these cultural heroes.”

“We have so many outstanding artists here, because of the tradition of art-making that goes back thousands of years on this coast, and because of the excellence of our art schools and university art departments.”

Since he left the VAG board in 2014, Audain has hardly shied away from advancing the arts. With his wife and collecting collaborator Karasawa, he built the remarkable Audain Art Museum in Whistler, opened in 2016, and endowed it with much of the art that once hung in their home: work by Emily Carr, E. J. Hughes, as well as a stunning collection of Indigenous masks, many brought back to B.C. from collections around the world. The photography-oriented Polygon Gallery in North Vancouver arrived at the foot of Lonsdale in 2017.

A third gallery will almost certainly open in Quebec, to celebrate Quebec artist Jean-Paul Riopelle, whose huge red-and-black abstract canvases, made with a palette knife, dominate Audain and Karasawa’s house today (and who is the subject of a major exhibition at the Whistler museum that runs until February 21). “Yoshi and I decided very early on, we like small museums,” Audain says, noting the couple’s discovery in Provence of La Fondation Maeght collection, founded not incidentally by Riopelle’s French art dealer.

For Audain, there is always a new house to build, new art to hang, and new futures to create. Holidays are coming, and he is looking forward to time with an infant great-grandchild, Iris Arbutus. Families, too, are gloriously complex constructions. Next door, the foundation for a new house is being laid, one Audain has described as Karasawa’s project.

As we walk through the current house, Audain telling me stories about the art, a horn sounds just outside to warn of an impending blast. He stops and is still, and then there’s a dull thud. Michael Audain flinches, just a bit.

Photography assistant Kit Woodland. Read more of Winter 2021.