A focused calm has descended on a workshop at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin’s newest museum of human history. Outside, the stone façade is cold and grey, but inside, the atmosphere is warm. A group of international delegates, from Namibia to the Amazon, sit in circles on pillows, speaking in hushed, excited tones. Papers are passed back and forth, then taped to a whiteboard. A word map begins to branch out and take shape, with headings such as “Restitution,” “Treasures,” and “Community.”

One of the participants is celebrated Haida artist and activist Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas, recognized for his signature hybrid Haida manga artwork and graphic novels. His work has graced the walls of the British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the American Museum of Natural History.

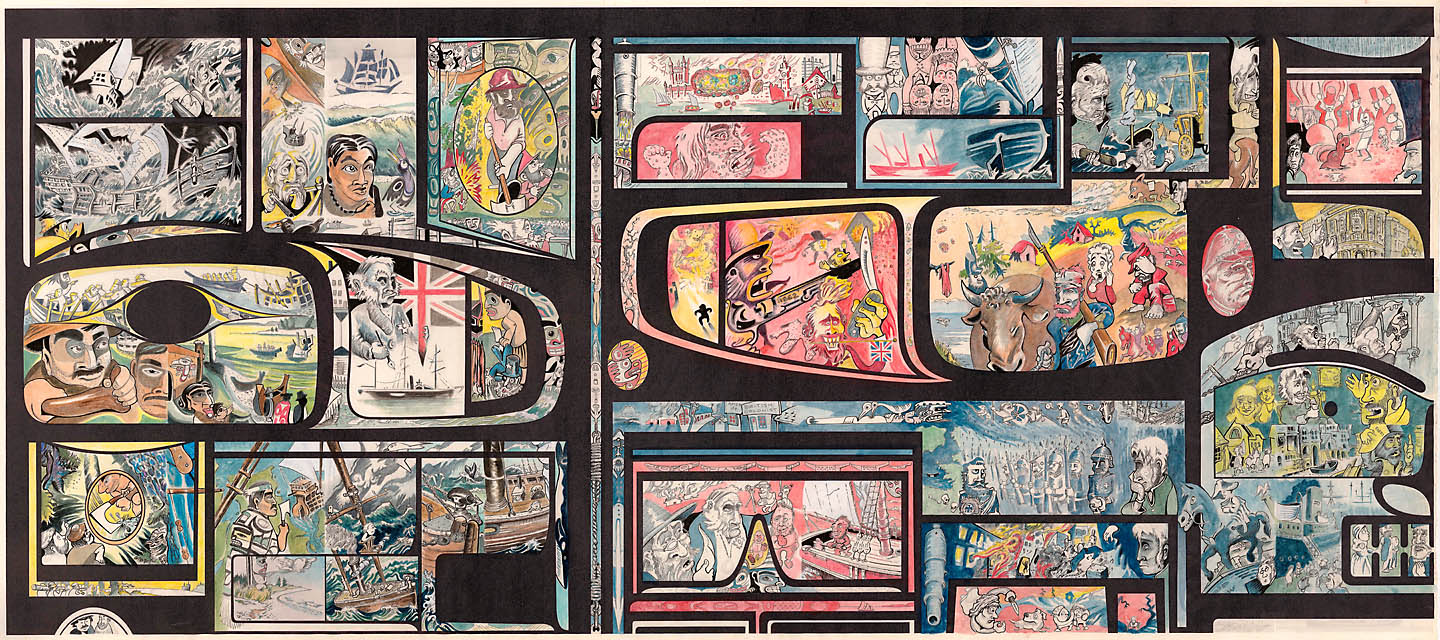

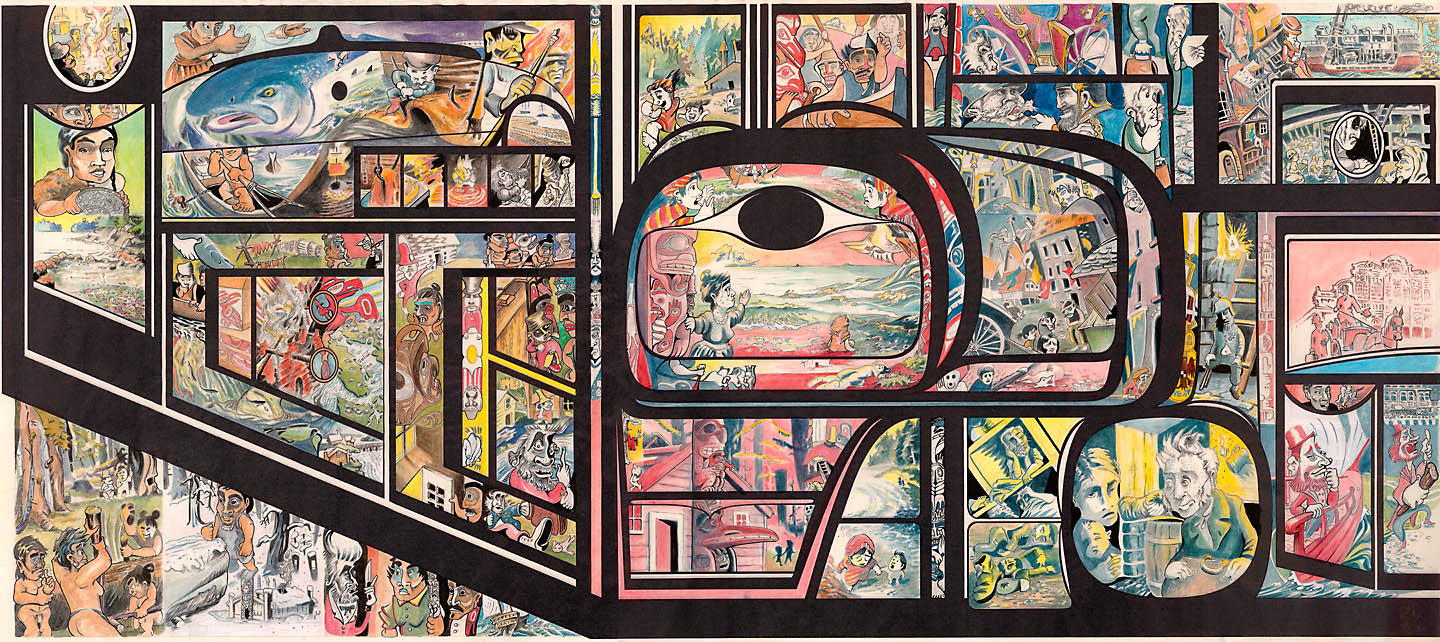

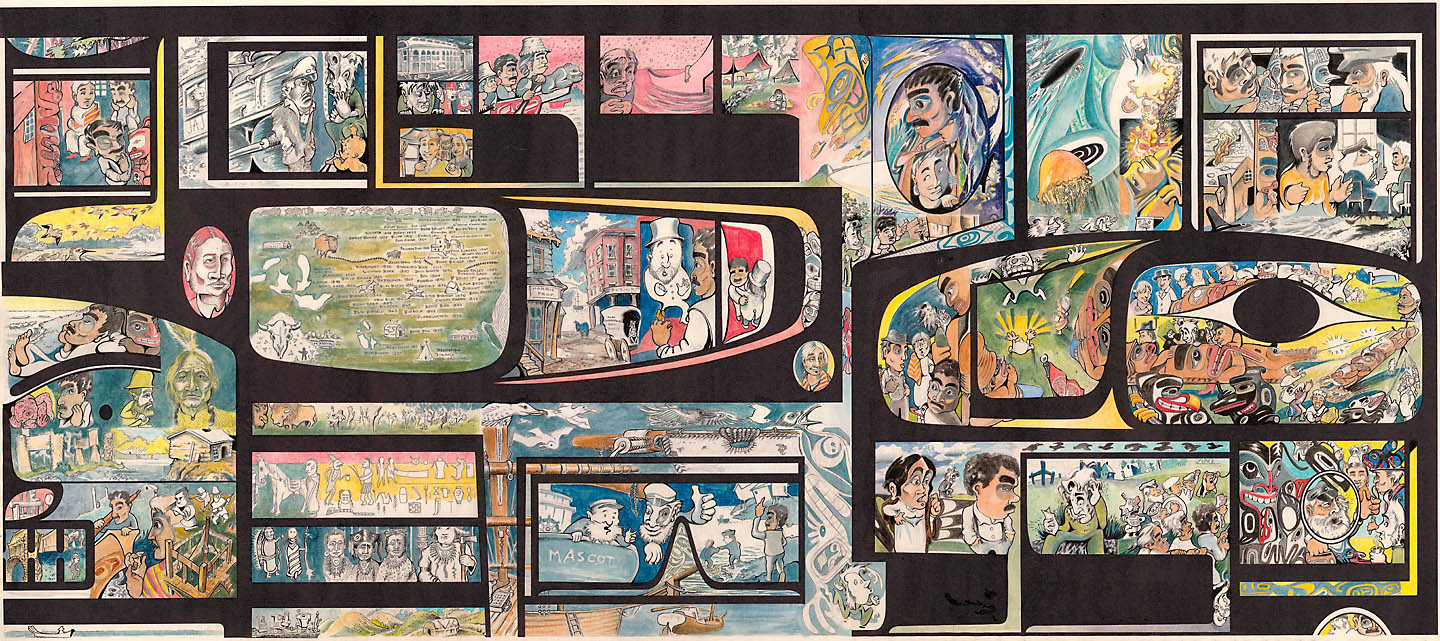

But today, in early September, he is in Berlin: another city of art and artists. With a bright-white shock of hair and a backpack swinging off one shoulder, Yahgulanaas bounds through the Forum’s main foyer and upstairs to the second floor. Next door, his newest mural quietly awaits its permanent unveiling—an eight-square-metre work he says may be the largest watercolour-and-ink mural in the world. The mural was commissioned by the Humboldt Forum in 2021 for the opening of its Ethnological Museum’s east wing, one arm that makes up the institution’s many moving limbs.

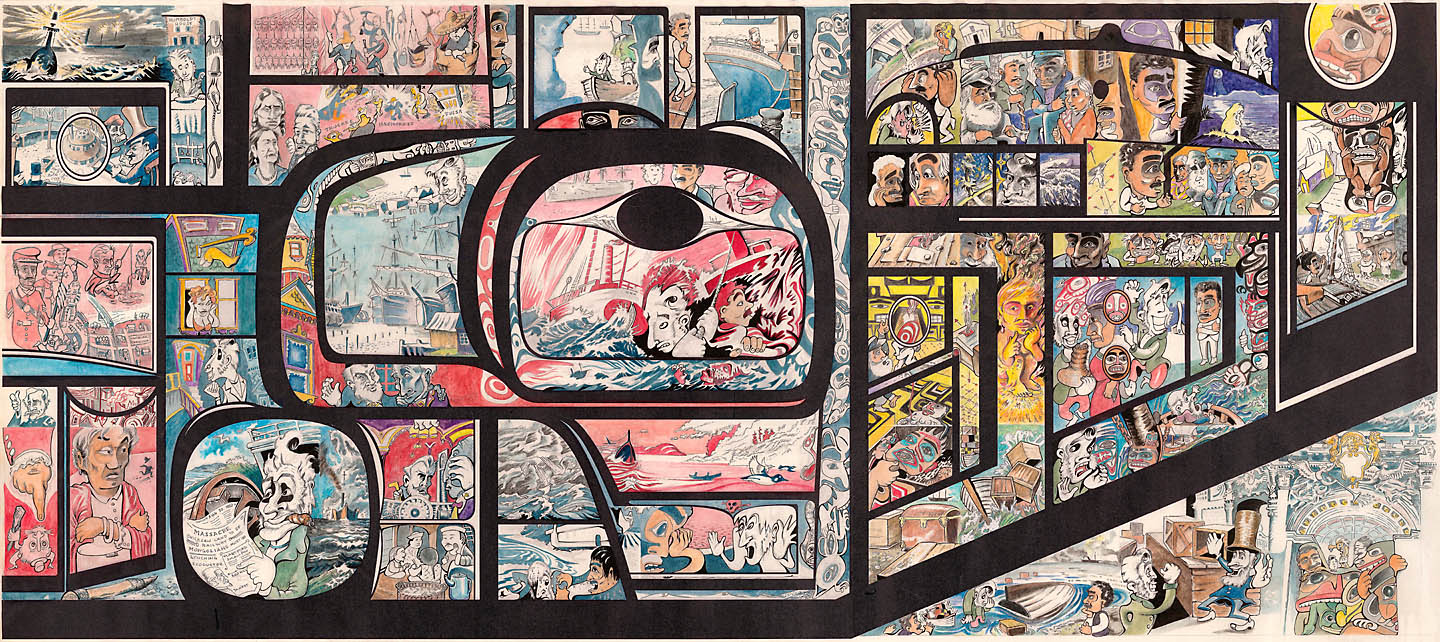

“It plays with the idea of the monument—whether it be a great building, a synagogue or a church,” Yahgulanaas says of the work. His latest mural is an attempt to confront that sense of monumentality. “You look at it, and there’s so much going on. You know there’s a story there. But it’s difficult to read. And that’s intentional.”

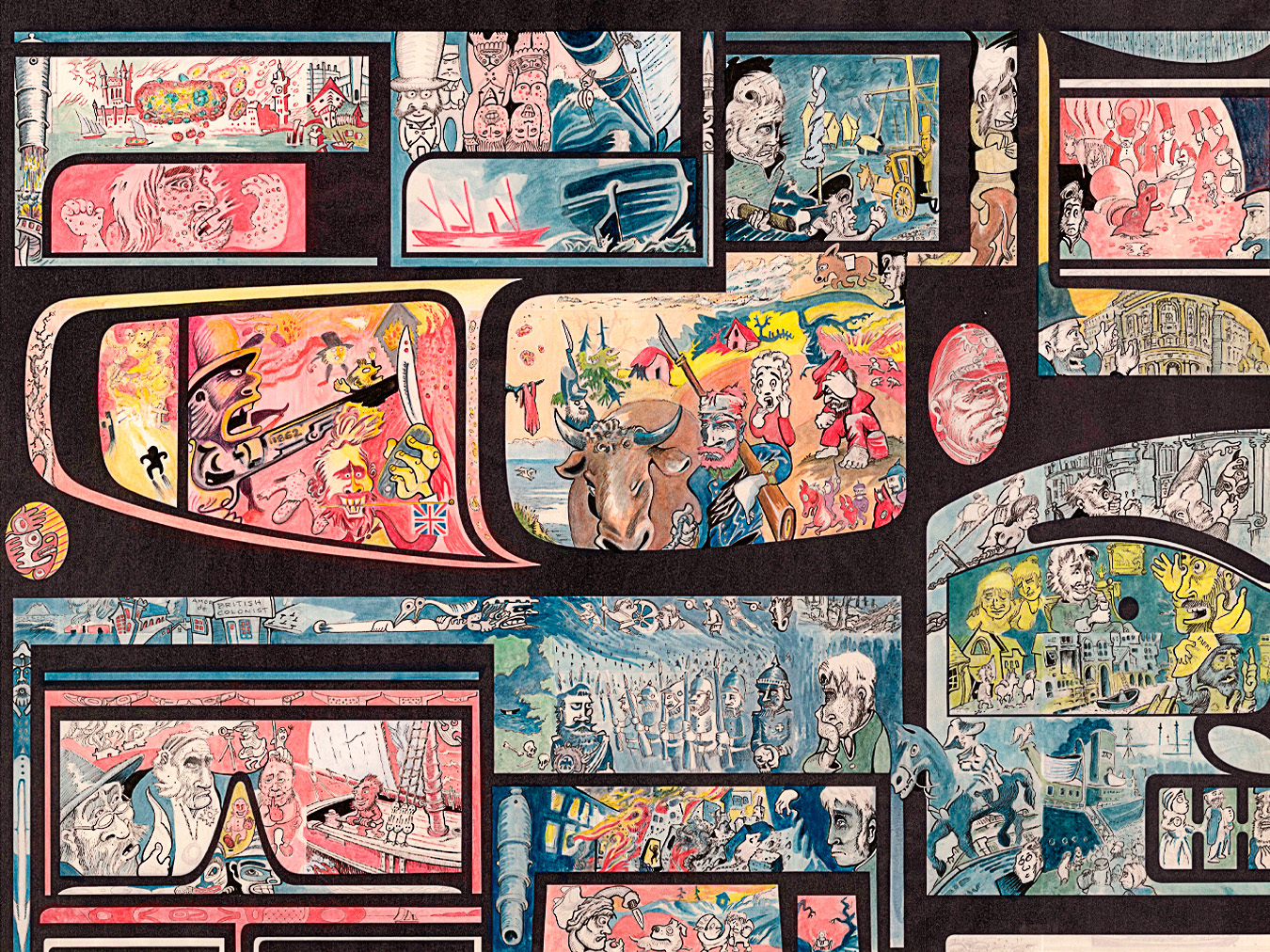

Down the hallway from where Yahgulanaas sits is the West Coast North America exhibition in Room 202. It’s dimly lit, and the smell of fresh varnish lingers. Here, you must peer closely through the glass to fully appreciate what’s inside: a Heiltsuk paddle, a Haida rattle. In the far corner, his mural hangs in four rectangular panels. The paper is mulberry and handmade by the Kubota family in Western Honshu in Japan. “It’s so strong. It’s so resilient,” Yahgulanaas says of the material. “I wanted that, because if it’s going into an institution, we want it to last.” A graphic novel will be published next spring to go along with the mural, but for now, the viewer can find their own meaning.

“You’ve got a new building. We’ve got a new start. What are we going to do now in a very collaborative manner?”

Titled JAJ, the mural tells a complicated story of exploration, ownership, and ambition. Four black eyes gaze out, designed in Yahgulanaas’ bold formlines, and a subtle wink at the relationship between art and audience. Painted in ocean-blue and flushed-red hues, it tells the story of a young Norwegian fisherman and budding ethnologist, Johan Adrian Jacobsen. He was commissioned by Berlin’s Royal Museum of Ethnology in the 1880s to sail to the Pacific Northwest, from the territory of the Nuu-chah-nulth in the south to the Tlingit in the north.

“As much as it’s a story about Jacobsen in 1882 going to the west coast to collect objects, it’s about one person’s journey and dashed expectations,” Yahgulanaas says. When Jacobsen returns to Berlin with thousands of pieces, many of which were brought back from Haida Gwaii, his career at a big German institution never materializes.

“The more I read into the story, I started realizing this guy was disappointed. He never got what he thought was coming to him,” he says. In the mural’s retelling, Jacobsen meets Yahgulanaas’ great-great-grandfather, George, who ultimately sees Jacobsen “as a man who really just wants a job and a family. And so he sees him as a human,” Yahgulanaas says. “It’s a story of how they work together briefly to pull this collection together.”

How can art help us better understand each other? This question is central to Yahgulanaas’ work. “Perhaps it wasn’t an earth-shaking event for Jacobsen or for George, but it becomes an opportunity for us to say, ‘Well, this is kind of strange. These two people can come together and create something.”

“The whole history or story about Jacobsen and collecting is being critically viewed in that exhibit,” says Tina Brüderlin, the director of the Ethnological Museum at the Humboldt Forum. And in Room 202, a decolonial approach is tangible. Curatorial statements address the way museums in the 19th century “rescued” objects of allegedly threatened societies. Wandering through the entire east wing, one senses a new eagerness to centre Indigenous voices.

“I really appreciate that Michael took on the task to really engage with the history,” Brüderlin adds. “Not only the collections that are housed in Berlin, but also about the individuals that are linked to that collection.”

This is now the gargantuan task of an institution that has, over the years, become a controversial symbol for Germany’s imperial aspirations. The site has been home to a medieval monastery, then a Prussian palace. That grand neoclassical edifice was damaged during the Second World War and later became the modernist home to the East German parliament during the Cold War. It was subsequently torn down to make way for the Forum, a replica of Berlin’s former palace.

In 2002, the government approved a plan for Germany’s answer to the British Museum. It went on to become one of Berlin’s most debated recent projects, lambasted for design choices and overspending. Activists argued that the institution did not go far enough to examine the provenance of its objects. In particular, the museum’s hoard of Benin Bronzes has become a lightning rod for anticolonial critics of the Forum. Now, most of the bronzes are set to be returned to Nigeria, with some pieces staying on loan to Berlin.

“Some may argue it’s the trophy of imperialism,” Yahgulanaas says. “And physically that is likely true, to a certain extent. Jacobsen’s collection is a mixture of transaction, and perhaps a little bit of thievery—an attitude that was reasonably common at the time. But nevertheless, those are the objects. How are the objects presented is a different question altogether.”

One way to take that on, Brüderlin says, is to bring the contemporary in conversation with the historical. “The historic objects have a very strong present significance, and so what better way to do that than have contemporary artists and curators tell these narratives?” Haida Gwaii Museum consulted on the exhibition, with curators such as Jisgang Nika Collison contributing critical commentary on Jacobsen’s travel logs.

Another way forward is genuine collaboration. On the day of the opening, Yahgulanaas took out his blue and green markers and spontaneously started a new artwork on the backside of a showcase. Yahgulanaas’ nephew, the animator Christopher Auchter, illustrated beside him. They signed the sketches: “An uncle and a nephew.” It was a gesture that moved Brüderlin. “It just shows that ‘Okay, we’re here,’” she says. “‘Let’s create. Let’s use the space that’s here.’”

At the end of the week of workshops, the group of around 80 delegates put forward a joint call to action to the Forum. Chief among the recommendations is a wish to focus on international and intercultural partnerships—and for the “objects” housed in the complex to be understood instead as “cultural belongings.”

“You’ve got a new building. We’ve got a new start,” Yahgulanaas says. “What are we going to do now in a very collaborative manner?” For Brüderlin, that means setting up space for residencies and research opportunities for artists and knowledge holders alike. “Michael was the driving force,” she says. “It is our task now to follow up.”

Ultimately, Yahgulanaas sees this new institution the same way he views his artwork: as a way for people to become engaged. “The metaphor that is often used is walls,” he says. “I like to think of building windows and doorways through walls.

“And then it’s up to individuals,” he suggests, “should they decide to walk through.”

All photos courtesy of the artist. Read more from our Winter 2022 issue.