Standing in the sunshine outside Hli Goothl Wilp-Adokshl Nisga’a, the Nisga’a Museum, Kari Morgan K’alaajex leaned in to examine the workmanship on the House of Ni’isjoohl memorial pts’aan. Her great-great-grandfather, Nisga’a master carver Oyee, created this pole almost 200 years ago. Yet today was the first time she, and others from the Nisga’a Nation, had seen it. “I walked into this not knowing how to feel,” she said. “This is the first sun it’s felt in 94 years.”

The western red cedar from the lower banks of northwestern B.C.’s Nass River started its long journey in the 1850s, just as the Nisga’a Nation entered a time of immense turmoil. Joanna Moody, matriarch of the House of Ni’isjoohl, commissioned the pole that Oyee and his assistant, Gwanes, breathed to life with the story of Ts’wawit, a warrior in line to be chief when he was killed in battle. Raised in the village of Ank’idaa, the 11-metre pole was tasked with preserving the family’s connections to the world while keeping Ts’wawit’s memory alive.

Instead, it watched over a different future. As new settlers were drawn to the abundance of the Nass, epidemic waves assaulted the Nisga’a. No one is certain how many people died over the decades, but by 1889 many of the large, traditional villages were empty, and the Northwest Coast Indian Agency census counted just 805 survivors.

Vulnerable and diminished, the Nation reeled from the lost familial lines, cultural leaders, and traditional stories. The Potlatch Ban dealt the next blow, outlawing the beliefs and practices that wove the Nisga’a together. This was followed by the establishment of residential schools and the removal of school-aged children. Missionaries were ready: they pushed the Nisga’a to convert to Christianity, warning their attachment to pagan beliefs was to blame for their devastating diseases. “Within the Nisga’a context, missionaries evangelically invaded the Nass Valley and, for the most part, forced us to let go of our priceless cultural belongings,” Sigidimnak’ Noxs Ts’aawit Dr. Amy Parent, Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Education and Governance at Simon Fraser University, wrote of the time.

Photo by Neil Hanna.

With Indigenous people under cultural assault, ethnographic expeditions set off for every corner of Canada with the goal of collecting as much as possible. In 1927, Marius Barbeau, an anthropologist with the National Museum of Canada, arrived in Nisga’a territory. Famous for gathering and recording stories and songs in Quebec and from the Pacific north coast, the inveterate collector, who characterized himself as “always grabbing,” had recently turned his attention to totem poles.

At first, Barbeau tried to purchase Nisga’a poles from their ancestral owners. He approached Chief Sagaween, the elderly owner of a 24-metre pole in Gitiks, offering to buy the impressive piece for the Royal Ontario Museum. In an indication of the pole’s cultural value and the chief’s wry humour, Sagaween turned down the money but told Barbeau, “Give me the tombstone of Governor James Douglas; I will give you the totem of my grand-uncles.”

Sim’oogit Ni’isjoohl (Chief Earl Stephens) with the Ni’isjoohl memorial pole in the National Museum of Scotland, August 28, 2023. Photo by Duncan McGlynn.

Despite failing to secure this initial sale, Barbeau sent photos of Nisga’a poles to museums around the world. Finding buyers for at least four of Ank’idaa’s, as well as the Sagaween pole, he returned in 1929. Arriving in Ank’idaa when the inhabitants were away hunting, fishing, or harvesting berries, Barbeau and his team cut down the village’s poles. Bundling them onto a raft, he floated them down the Nass River and onward to museums in London, Paris, Toronto, and Ottawa. The Ni’isjoohl memorial pole was purchased for between $400 and $600 by what is now the National Museum of Scotland (NMS).

“Elders said [the poles] were gone. They didn’t understand why—they were just told that they couldn’t have them anymore. There was so much pain and emotion no one could talk about it after that,” President Eva Clayton of the Nisga’a Nation explains. Though overwhelmed by what Parent calls a “colonial storm,” Nisga’a elders turned to the Nation’s future. On May 11, 2000, after decades of fight, the Nisga’a Final Agreement between the Nisga’a and the governments of Canada and B.C. came into effect, codifying the Nisga’a’s right to self-governance, ownership of 1,992 square kilometres of hereditary land, and access to traditional foods.

The treaty also paved the way for the return of over 300 stolen belongings housed in Canadian museums—an unprecedented act of repatriation. But there was a catch: the belongings had to be conserved in a Class A museum, a structure that would cost the Nisga’a approximately $14 million.

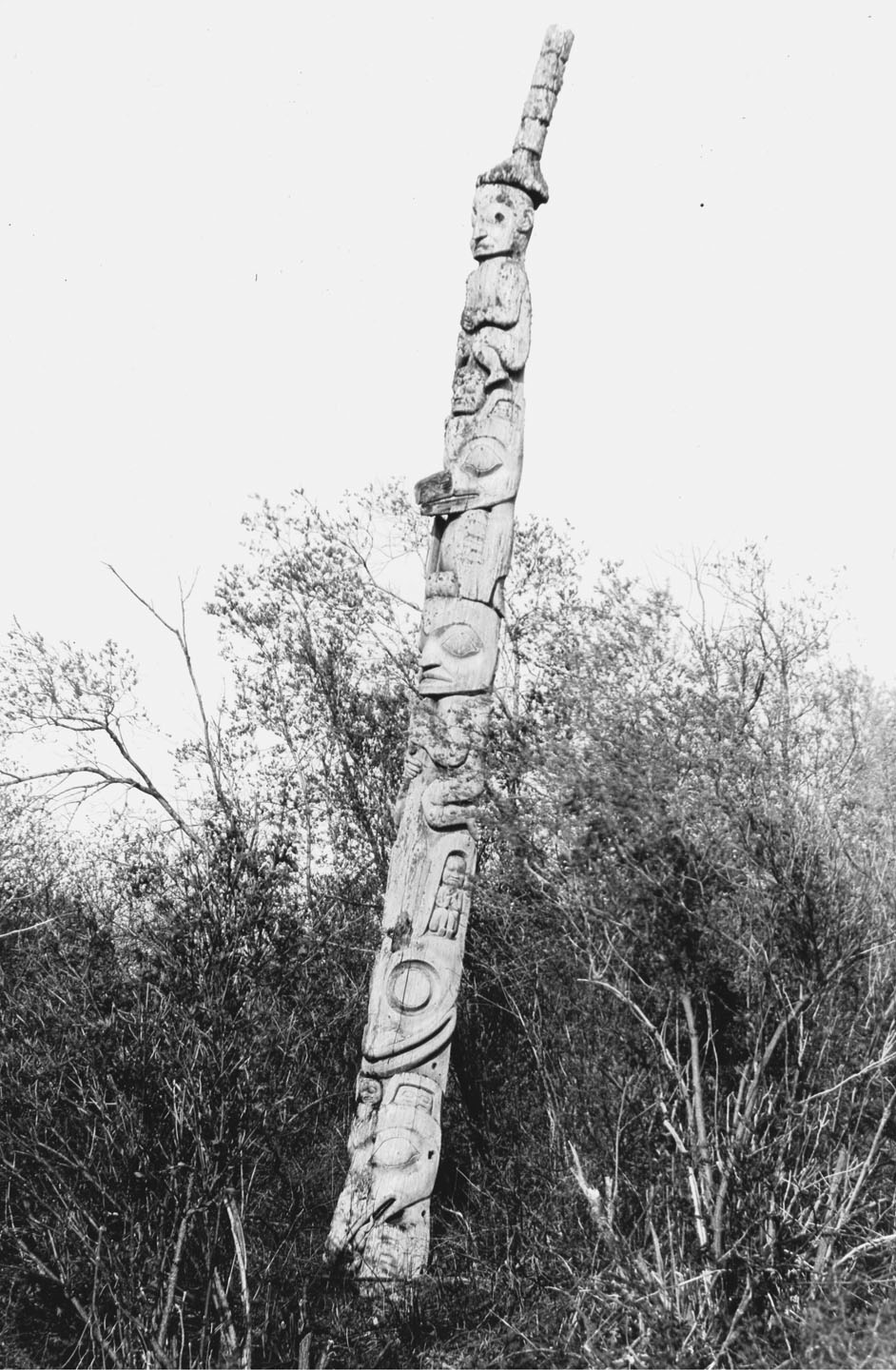

This archival photo from The Bill Reid Centre’s Digital Image Archive shows the memorial pole in the village of Ank’idaa, its original home.

Though the movement to repatriate looted items is growing, thanks in part to the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which highlighted the need to “enable the access and/or repatriation of ceremonial objects,” it’s not a simple process. Theresa Schober, the Nisga’a Museum’s director and curator, says even the best-intended policies “put all kinds of obstacles in the way of the people who were subjected to the thefts in the first place.” But the Nisga’a, buoyed by their Canadian success, were ready to try in Europe.

“We explained the Nisga’a treaty and that we didn’t need Canada or B.C. to be there negotiating on our behalf.” —Sigidimnak’ Noxs Ts’aawit Dr. Amy Parent

In August 2022, a seven-person delegation, including Parent and Schober (a non-Nisga’a witness), journeyed to Scotland to secure the memorial pole’s return. Initially, NMS staff didn’t understand why the Nisga’a Nation wasn’t represented by the federal or provincial government. “We explained the Nisga’a treaty and that we didn’t need Canada or B.C. to be there negotiating on our behalf,” Parent says.

Despite this, there was a clash of worldviews. Chanté St Clair Inglis, head of collections services at NMS, says while the museum had successfully returned human remains, repatriating belongings was new. Parent, who grew impatient with the overly complicated process, just wanted the stolen pole back. “We have to operate within U.K. charity law [which requires ministerial approval], so we had to follow the framework,” St Clair Inglis explains.

Members of the House of Ni’isjoohl and Nisga’a chiefs walk in a procession at the start of the arrival ceremony at the Nisga’a Museum in the Nass Valley on September 29, 2023. Photo by Aaron Whitfield, Red Bike Media. Courtesy of the House Of Ni’isjoohl and Nisga’a Lisims Government.

Despite the challenges, provenance identifying the hereditary owners was established through Nisga’a law, protocols, orality, songs, ceremony, stories, and crests. Photographs and written records proved Barbeau had no authority to sell it. (Though these colonial documents show agreement by someone from the House of Ni’isjoohl, that signature is believed to have been falsified since it contradicts the family’s oral history, according to the Nisga’a.) Removed from where it stood in front of Parent’s family’s longhouse, it is also considered an ancestor in the Nisga’a worldview, a living being that cannot be owned or controlled by a museum—a similar argument to ones used in Indigenous repatriation cases for human remains. Most importantly, members of the House of Ni’isjoohl were the ones making the request alongside the Nisga’a Lisims Government—Parent is Joanna Moody’s ancestral granddaughter.

Unfortunately, in most cases, provenance is harder to trace due to the loss of familial lines and oral histories. Anthropological explorers often got their details wrong, including which Nation artifacts were from. Museum collections around the world are a mishmash of mislabelled and unrelated objects. This means the onus is on Indigenous peoples to pay for the travel and the research, Schober notes.

Children from the House of Ni’isjoohl lay a protective border of cedar boughs around the memorial pole. Photo by Aaron Whitfield, Red Bike Media. Courtesy of the House Of Ni’isjoohl and Nisga’a Lisims Government.

Part of the solution could be for museums themselves to reexamine items procured during the Potlatch Ban (1885-1951). Parent says that while not everything from this time frame was stolen, “most objects were acquired under duress.”

To date, the only museum to do this voluntary work is the Buxton Museum and Art Gallery in England. In 2018, the museum received an archive containing sacred and deeply personal Indigenous belongings. Rather than selling or storing them, Buxton curator Bret Gaunt chose to return them to their rightful owners. Reaching out to experts in Canada and the U.S., he researched each item, eventually sending them home to communities including the Siksika Nation in Alberta and Haida Gwaii. Each return, Haida Gwaii Museum executive director Jisgang Nika Collison told the CBC, is “an incredible step forward in healing.”

Laxgalts’ap Cultural Dancers perform a song at the close of the arrival ceremony at the Nisga’a Museum. Photo by Aaron Whitfield, Red Bike Media. Courtesy of the House Of Ni’isjoohl and Nisga’a Lisims Government.

Despite early conflicts, negotiations between the Nisga’a and NMS eventually moved forward with goodwill. On December 1, 2022, the NMS board of trustees agreed the Ni’isjoohl memorial pole could go home. By January 2023, plans for the “rematriation,” a term reflecting that the Nisga’a are matrilineal, were moving quickly. In August 2023, the delegation returned to Edinburgh for a private ceremony to prepare the pole for its journey home.

International news outlets followed as the pole was packed into a crate, carefully moved from NMS, loaded into Canadian military aircraft, and flown to Canada. On the ground in Terrace, a procession of cars accompanied it 150 kilometres along Nisga’a Highway 113, past lakes and streams and through massive expanses of moss-covered lava—scars from the Tseax volcano eruption circa 1700. Reaching the Nass River, the procession wound past the villages of Gitlaxt’aamiks and Gitwinksihlkw before arriving at the Nisga’a Museum in Laxgalts’ap. Here, it was welcomed home by Nisga’a elders, leaders, cultural dancers, and guests and dignitaries from across Canada and Scotland.

Laxgalts’ap Cultural Dancers perform a song at the start of the arrival ceremony at the Nisga’a Museum. Photo by Aaron Whitfield, Red Bike Media. Courtesy of the House Of Ni’isjoohl and Nisga’a Lisims Government.

A few days later, the pole was raised in front of the museum. In a precedent-setting agreement, the rematriation came with no stipulations. The members of the House of Ni’isjoohl felt that “the pole was a survivor and had an important story to share with our Nation and the world,” Parent says. After gathering earth from Ank’idaa and incorporating the soil into the supportive base, the family witnessed the pole’s raising in a place of honour inside the glass-fronted museum. Rooted in soil from its home, the pole will share its story with the next generation, Parent says, surrounded by familiar belongings and language, and the people who love it.

Read more from our Winter 2023 issue.