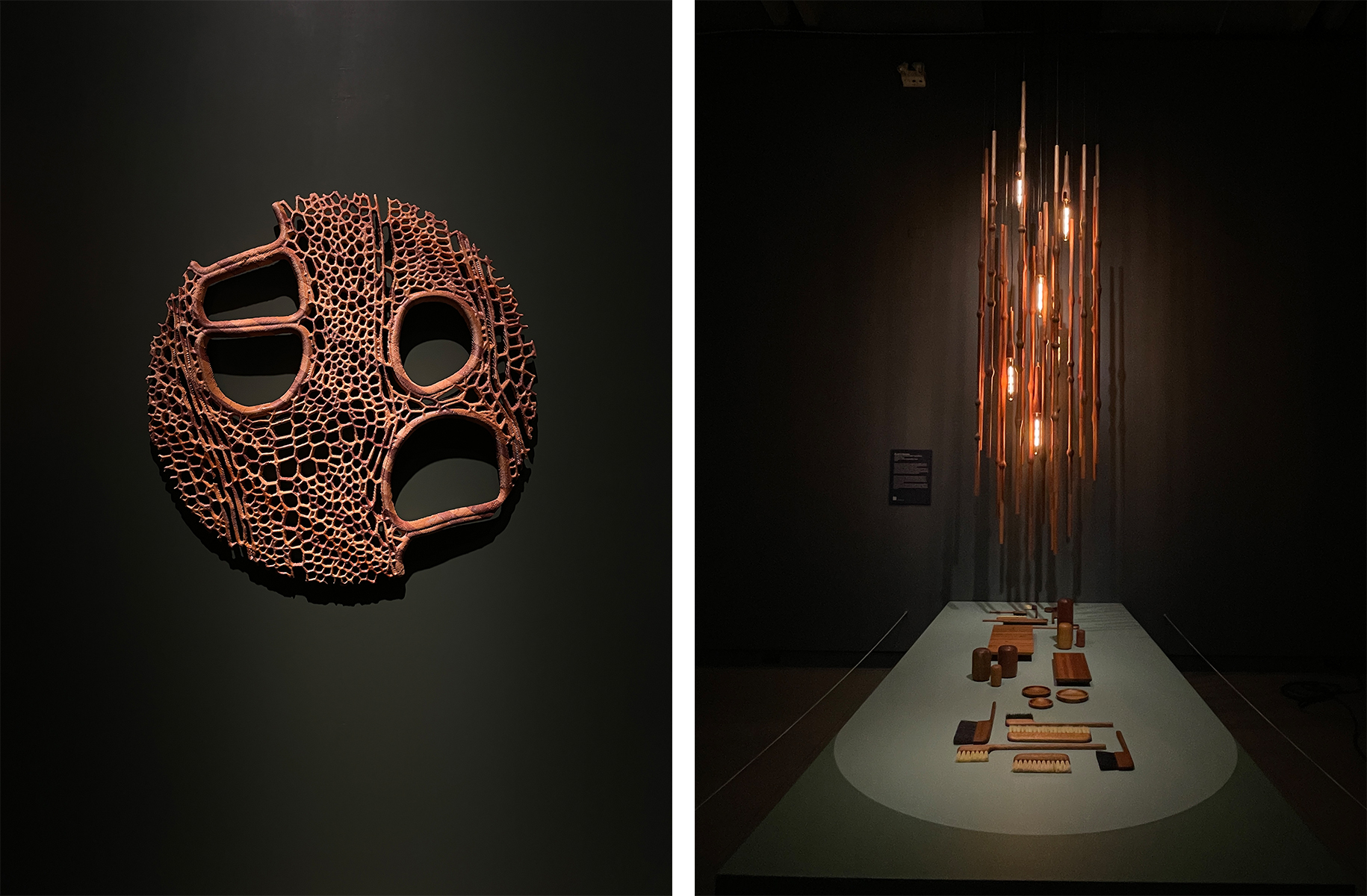

The wooden moon stares back at me. His placid face fat and round, his copper eyes small and shiny, ceramic tides dance in his orbit. The Moon, the Tide, and the Land That Brings Us Together (2023) tells a story of push and pull between celestial and oceanic beings. A story carved out of rich mahogany.

I’m standing in front of the work, a joint creation by artists Sage Nowak and Tyler James Goin, at the Museum of Vancouver (MOV). The overhead light casts a shadow across the sharp contours of the carved moon’s face, illuminating the gradient of blond and brown in the mahogany. The piece is a testament to the two artists’ friendship: Nowak and Goin went to high school together in Canmore, Alberta, and have spent the past decade or so flitting through each other’s lives—pushing and pulling against each other like the tide and moon.

But there’s another part to the story, and a shared through-line between this piece and the rest in the Reclaim + Repair exhibition at the MOV: the story of mahogany.

It began when the museum’s director of collections and exhibitions, Viviane Gosselin, received a call with an offer she couldn’t refuse. A surplus of mahogany planks, accumulating dust in a storage facility, was being made available to the museum. Harvested in Nicaragua and Guatemala from the 1950s to 1970s, the wood was exported to B.C. for use in the marine industry. But when the business that owned the wood shut down, tons of planks were left idle for years.

Photo of The Moon, the Tide, and the Land That Brings Us Together (2003) courtesy of Museum of Vancouver.

Gosselin took the wood but was left with a delicate challenge: how could she do justice to this beautiful material, which also had been grossly overlogged for decades? The tree was listed as an endangered species by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora in 2003, yet despite attempts at regulation, illegal logging of mahogany remains rampant across Central America, leading not only to a devastating disruption of ecosystems and habitats but also to an increase in criminal violence. The provenance of the wood given to the museum, Gosselin tells me, was carefully reviewed.

Considering the material’s contextual history, and the MOV’s commitment to practising sustainability, Gosselin wanted the mahogany project to connect with the idea of circular economies: reusing and reclaiming existing material. She decided to pair up with Propeller Studio, an independent and ecologically minded design studio, to gather artists who could engage with the mahogany in interesting ways, she says.

Spanning several rooms, the works are a diverse collection of furniture, jewellery, and design objects.

After a call-out to makers, designers, and artists across Greater Vancouver, the museum received 65 proposals for projects, of which a review board accepted 22. From there, the artists only had a few months to create their work before it was displayed in Reclaim + Repair (which runs until August 2024). Unusual for a museum exhibition, each work is for sale, with a third of the proceeds dedicated to Indigenous-led reforestation efforts in Central America. This is the “repair” part of the exhibition, Gosselin says.

Spanning several rooms, the works are a diverse collection of furniture, jewellery, and design objects, including a pair of chopine-inspired platform shoes by Nina Rozin, a luthier’s workbench made by designer Mario Paredes, and an acoustic guitar by Shelley D. Park.

Around a corner, the face of the moon peers back at you. The moon, enclosed by a copper ring, is carved into the centre of a large square panel, where coral-shaped, seaweed-coloured, glazed ceramic forms adorn the edges. The work is a collaboration between old friends Nowak and Goin, who were self-described “art nerds” back in high school—two sensitive punks who skateboarded and played music together.

Their artistic exploits matured from graffiti into sculpture, and they set off on their own paths. Nowak, who is from the Tahltan and Vuntut Gwitchin Nations, attended the Freda Diesing School of Northwest Coast Art in Terrace, B.C., to study formline carving. Goin, meanwhile, apprenticed under Canmore sculptor Tony Bloom and learned to work with metals and ceramics. The two reconnected for the mahogany project—their first professional collaboration—to tell the story of two friends who weave in and out of each other’s lives through the metaphor of the moon and sea (an implicit nod to mahogany’s popularity for boat-building).

Photos by Nik Rust courtesy of Museum of Vancouver.

They began by gluing the mahogany planks together, each plank from a different tree, leaving a mishmash of patterns and grains. This posed a challenge when it came to carving. “When you work with wood, you can only take the wood off from a certain angle. And the way that we had created that panel made the grain sort of turn a lot of different directions. It was complicated,” Nowak tells me, explaining that they spent hundreds of hours bent over, carving the wood. “You had to put your back into it.”

But perhaps that challenge—adjusting yourself around a reclaimed material and accepting the small imperfections that entails—is precisely what Gosselin had in mind with this exhibition. That extra effort permeates the artistic process in each of these works, a practice of working around existing materials rather than extracting raw resources.

“One of the takeaways is that urban mining is one part of the solution,” Gosselin says of the exhibition. “There’s so much waste still within industries. And designers and makers are resourceful individuals that can think of ways of reusing this material.”

Urban mining is the process of recovering raw materials destined for landfills to create art. This notion of the endless circle of creation and re-creation is inherent in Nowak and Goin’s piece.

“That mahogany tree has been recycled from the intention of becoming a ship into a sculpture,” Nowak explains. “Before that was a tree, it was a seed, and that seed fell from another tree—that tree’s grandparents. And now this art piece is a part of that tree’s life.

“We grow old. When we die, we become dust, and that nourishes everything around us. It’s all recycled, in a sense. And a part of that energy in our history gets sucked back into the land and then gets absorbed by the roots of these trees. And nature has all those old memories. And when I work with wood, it’s almost like I can feel them.

“I get to learn that old history,” he adds. “And in return, I get to make those memories physical again so they can retell their stories.”

Read more from our Winter 2023 issue.