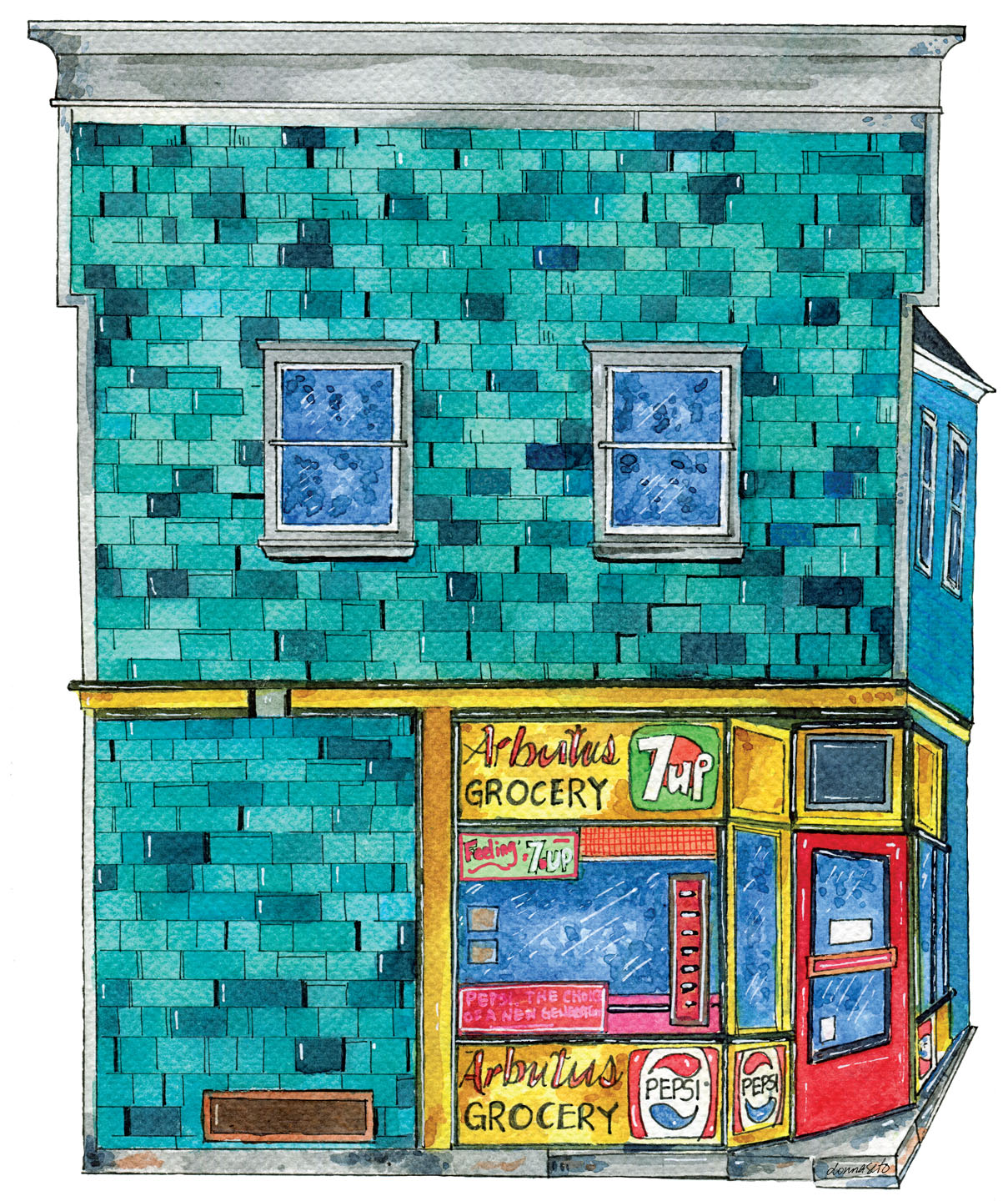

Even before she moved to Vancouver in 2021, Kimberly Krejsa had decided she would work at Arbutus Coffee. Krejsa, a native of Hamburg, Germany, had looked through Vancouver coffee shops on Instagram and was taken by an image of the Arbutus store in the snow. Located in a 116-year-old heritage building, it looked, she recalls, “so cozy and romantic.”

Once in Vancouver, she dropped off her resumé. She is now the manager.

Little did Krejsa know when she paused on that social media post that Arbutus Coffee is a unicorn in Vancouver’s coffee scene. Not only is it an independent business in a sea of local chains, but it is charmingly secluded, sitting in the middle of a residential neighbourhood a few blocks between Kitsilano’s commercial arteries on Fourth Avenue and Broadway.

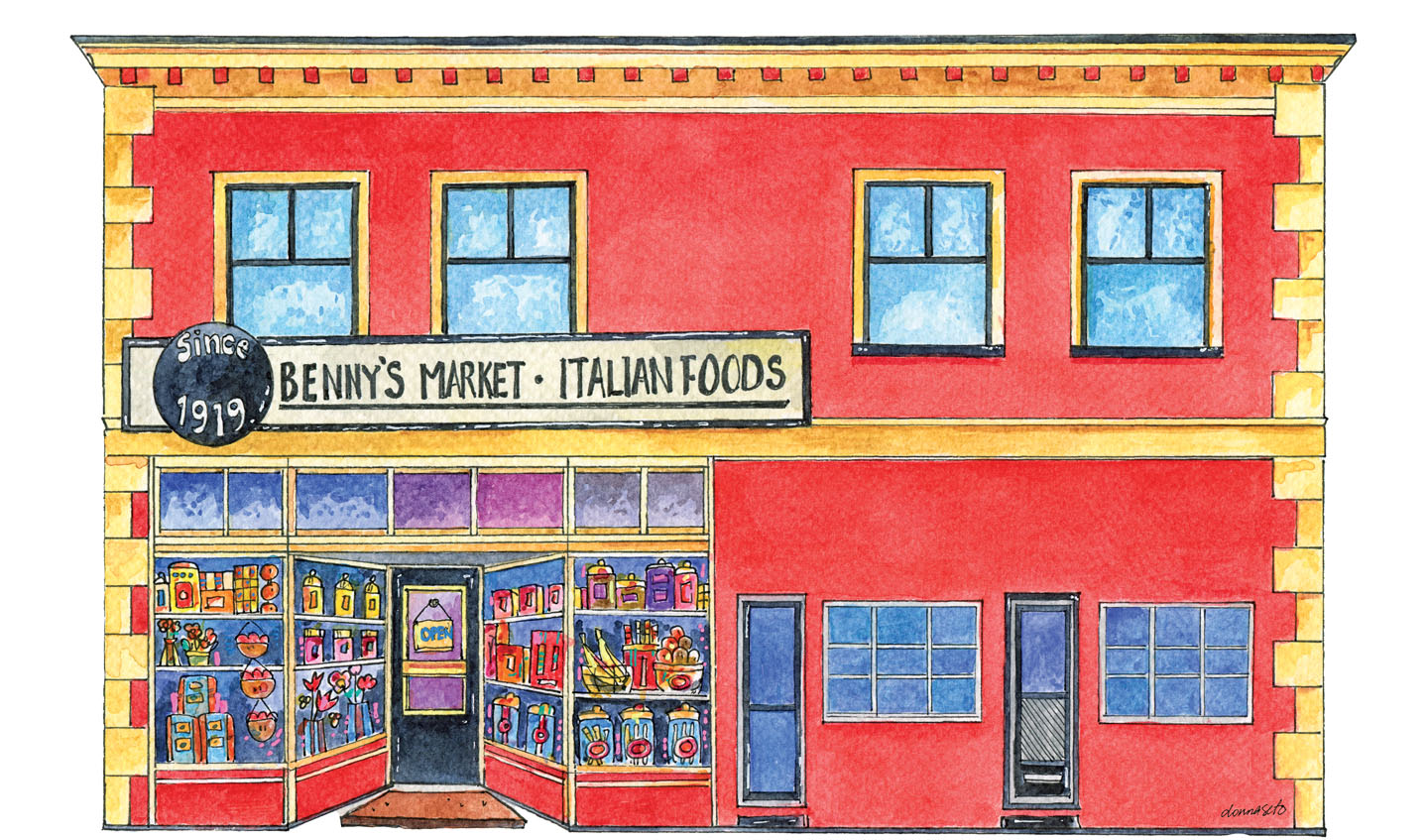

Corner stores like Arbutus Coffee (originally named Arbutus Grocery) are having a renaissance. Legacies from a simpler time, they’ve long inspired nostalgia for an era when one’s universe was limited to the few blocks around one’s house, and the store held all its treasures: candy, pop, comic books. “We do have some of the old timers pop in for nostalgia purposes,” says Ramon Benedetti, who runs Benny’s Market, which was first opened for business by his grandfather in Strathcona in 1919. “People come in going, ‘Oh, my grandfather brought me here to the store when I was just a little boy.’” For many immigrant families, they were 24-7 live-work spaces and the first rung on a multigenerational socioeconomic ascent.

And yet these stores, lone islands of commerce in otherwise residential neighbourhoods, anticipate contemporary urban planners’ calls for urban density and the “15-minute city”—the concept that a city-dweller’s needs should be accessible within a 15-minute trip on foot, bike, or mass transit. Yet the number of corner stores in the city has steadily decreased from its peak of 260 in the 1920s (when newly introduced zoning bylaws kept new retail businesses from residential areas) to 105 in the 1970s and now to its current 88. The question remains whether, and how, the city can support these small businesses.

The history of Vancouver’s corner stores, with their cola-branded signage, goes hand in hand with the life stories of the immigrant families who operated them. Benny’s Market was launched as an ice cream parlour by Alfonso Benedetti, who emigrated from the Abruzzo region of Italy to the then-burgeoning Italian community in Strathcona. Like many of its contemporaries, Benny’s retail space is connected to living quarters. One of the apartments remains occupied by the store’s current owner, Irma Benedetti, who ran the business with her husband, also named Ramon, for decades.

The younger Ramon notes how the store has adapted as the area’s demographics shifted. “Originally the neighbourhood used to be mostly immigrants: Italians, Yugoslavians, and some Croatians. When the Italians and some of the others started to move out, the Asian population started to move in. Now a lot of the Asians are moving out, and you’re getting more Canadianized, white people moving in. As far as businesswise goes, we adapt to what the customers want.”

There’s a reason Benny’s and businesses like it are sometimes described as variety stores. Alongside the famed Benny Burger and corner-store staples like chips and milk, Benny’s also sells specialty Italian ingredients such as clam nectar. Behind the counter, one can also find local art, air fryers, and Himalayan salt lamps. The salt lamps, Benedetti says, come from one of his food suppliers and sell briskly.

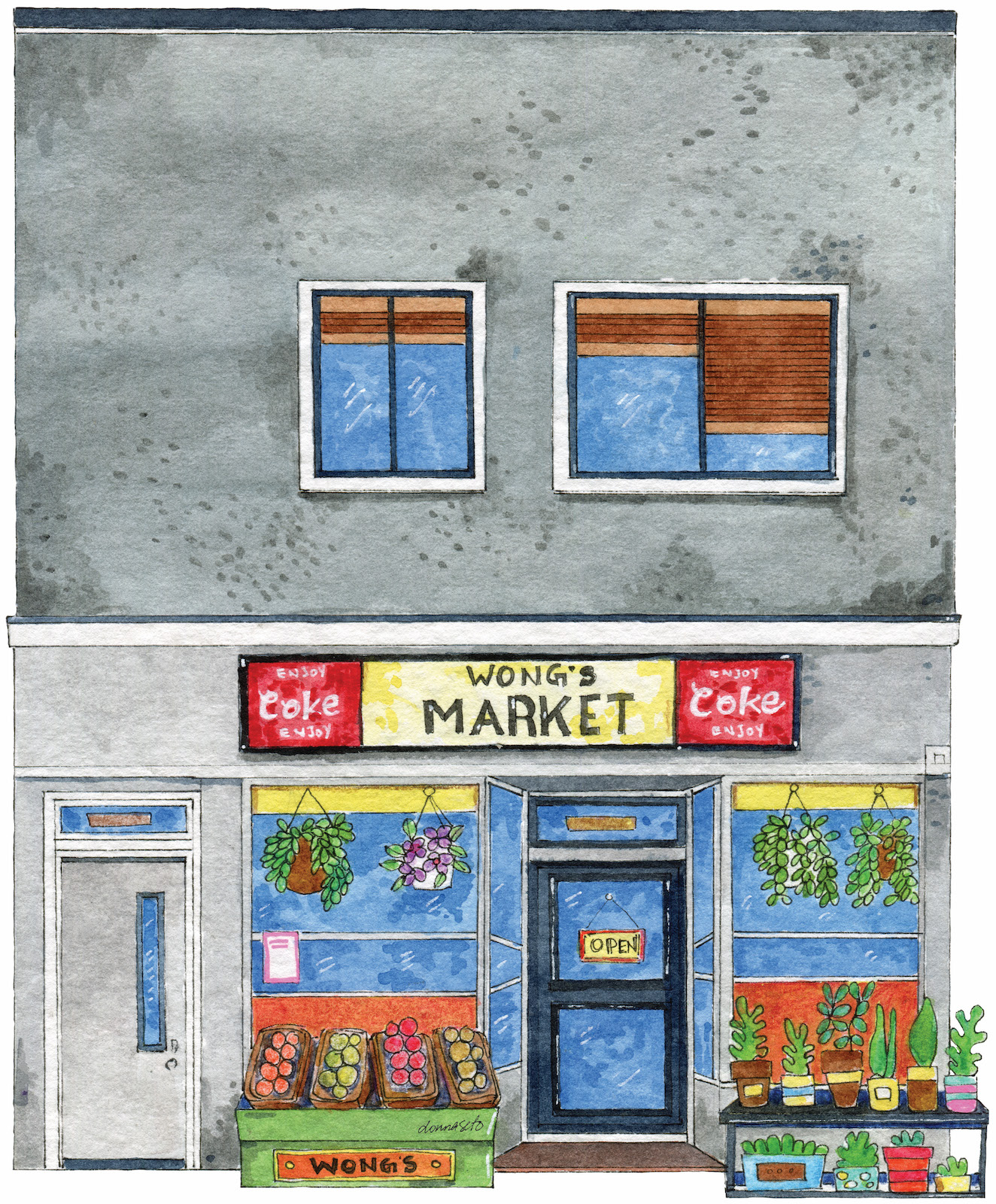

In contrast, the now-defunct Wong’s Market, located among a stretch of homes on Main Street at East 44th Avenue, changed owners—and business names—many times. It first opened as the Winnott Store, a post office and grocer, in 1911. At one point, according to Michael Kluckner’s book Vanishing British Columbia, the store sold dynamite—more specifically, the “stumping powder” used to clear tree stumps from stretches of then-undeveloped South Vancouver. In the late 1930s, the business was purchased by the Fukuharas, who lost their property and their freedom when 22,000 Japanese Canadians were forcibly incarcerated and relocated in 1942.

The pace and clientele of a corner store allow for a different kind of relationship between operators and customers.

For decades, the Wong family operated their corner store. “Mr. Wong would sit out front behind the counter and there was a Coke crate tipped on its side with a piece of carpet on it,” says one of the property’s current owners, Mike Jackson. “And that was his little spot where he’d sit behind the cash register, and he had all these mirrors up for people trying to shoplift and had all these locks and all these alarms and doors and little secret spots for all this stuff. And Mrs. Wong would generally sit near the back of the store on another stool doing something else.”

Intrigued by its history, Jackson and his partners purchased the property from the Wongs’ children in 2021, a few years after the market went out of business. “We did a walk-through, and it was essentially infested with creatures,” says Jackson, who runs Jackson’s General Store on Kingsway, which specializes in local, B.C., and Canadian homeware, gifts, candy, and coffee. “There was lots of stuff still on the racks and shelves, dried goods specifically. It was a step back in time.”

The pace and clientele of a corner store allow for a different kind of relationship between operators and customers. “We have this old lady that’s over a hundred years old,” says Krejsa at Arbutus Coffee, which prides itself on its house-made pastries. “She gets her coffee every day here—or more often her friend picks it up for her these days. They’re our regulars, these two old ladies.”

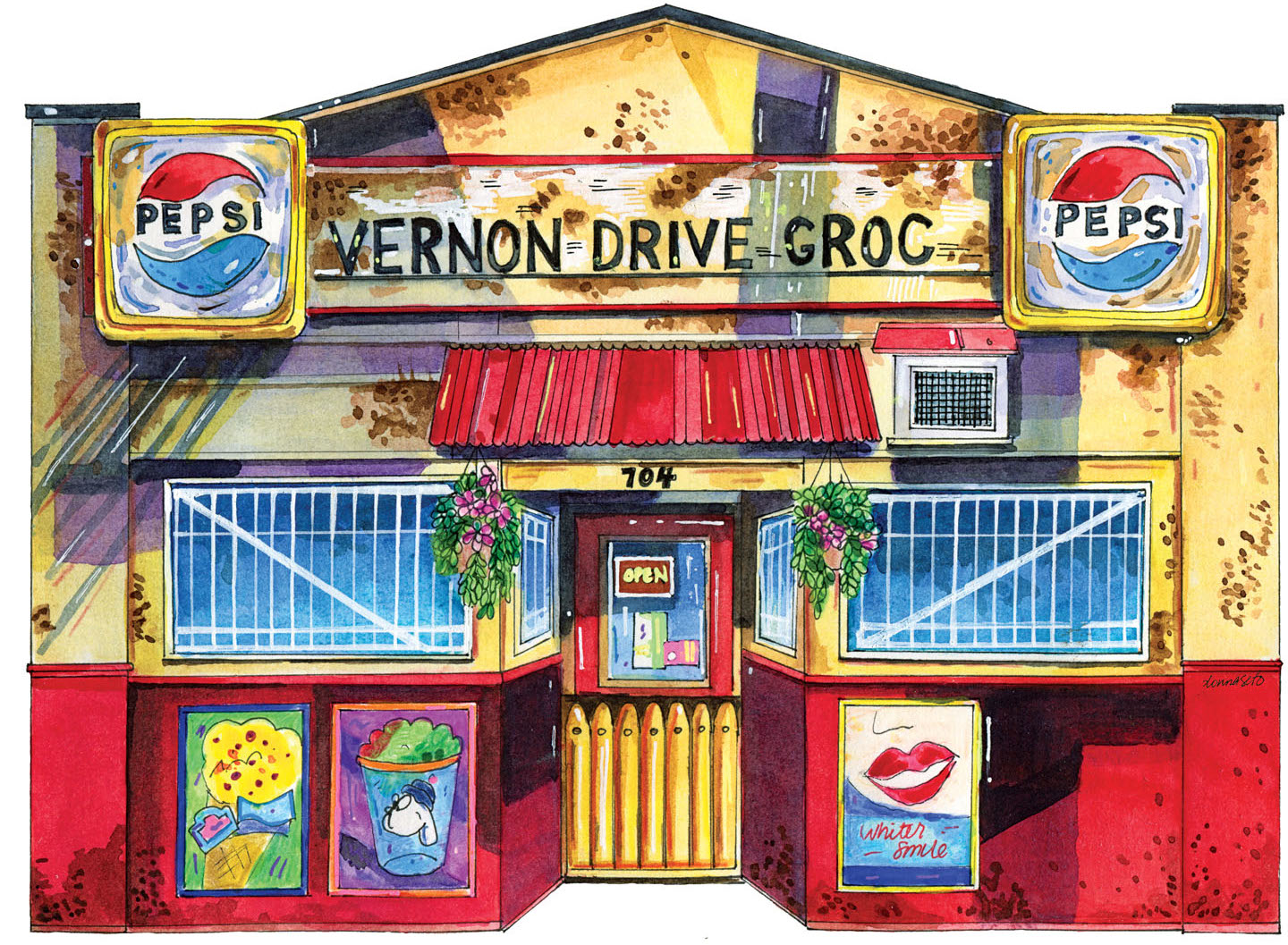

When, in 2021, Roger Collins opened Rise Up Marketplace in the former Vernon Drive Grocery, which opened in 1904 (and is likely one of the most photographed storefronts in the city), he was surprised by the bonds he developed with the students and staff of Admiral Seymour Elementary across the street.

“I have probably 20 new friends under the age of 12,” Collins says. “We get a lot of teachers in here. So it’s great to be able to support their needs when they want lunch, or the kids come after school and we have 10-cent candies and 25-cent lollipops.” The store has also become a hub for Vancouverites with African or Caribbean roots who come for Jamaican patties and coconut bread, which share space with handmade scented candles and pottery.

This past September, the City of Vancouver launched a community survey to seek input on ways to protect corner stores as “cherished assets.” For Ramon Benedetti, the problem is clear: “Property taxes just are killing us.” Benedetti notes that Benny’s Market is run alongside another family business that supplies ingredients for high-end restaurants such as Elisa and Savio Volpe. Without this synergy, he says, they wouldn’t be running the store.

Originally, Jackson purchased Wong’s Market with the idea of launching a second general store. Instead, he and his partners have renovated and rented out the building’s apartments. “It’s part of the neighbourhood, and I really wish we could have opened a store there,” he says, “but it probably would cost another $50,000 to $75,000 in renovations to do it with permitting and licensing.” Describing the onerous process of obtaining permits, he notes that the city staff are “just not that friendly. They’re not Yes people. They’re No people.”

Collins cites corner stores in Ontario and Quebec being allowed to sell beer and wine and how more latitude around permits could help corner-store owners. “If we could do more here,” he says, “we could generate more.”

Any initiatives by local government likely wouldn’t change the huge effort these stores require. All the owner-operators talk about working long hours, often seven days a week.

In a sense, the slow decline of the corner store can be seen as a positive—the realization of the immigrant dream. The toil and sweat of these shopkeepers are often in service of providing an easier life for their children, one away from the family business.

“My kids don’t want it,” Benedetti, now 62, says. “They’re making more money than I’m making right now. And they see the hours we put in.”

Collins, however, has started taking his 10-year-old son on errands in the hope that the work might pique his interest. “It’s not the kind of thing where you open up a corner store and then you’re never here. You have to be in touch with the community and with the store’s needs,” he says about running Rise Up. “You’ve got to love what you’re doing to run a corner store.” Feeling, and receiving, so much affection for a neighbourhood over decades, Collins can see his business becoming his legacy.

Read more from our Winter 2023 issue.