My first encounter with the work of Firelei Báez is a jolt to my system. Fighting sideways sheets of November rain outside the Vancouver Art Gallery, I’m transfixed by a banner that wraps around the entire northern façade of the building. It shows a female figure crouching low on a sea of white and cerulean waves, its body covered in scales of every colour: magenta, persimmon, deep red, and gold. The colours converge where its head should be, but in its place is an explosion of sharp, textured petals that suggest a flower. The image, incongruous with its grey surroundings, commands attention.

Firelei Báez is a Dominican-born, New York-based artist who for the last 20 years has created vibrant, immersive paintings, sculptures, and installation works that involve the viewer in her richly layered universe. This career-retrospective exhibition, which runs through March, is the first of its kind on North America’s West Coast.

“Firelei is a storyteller,” says Eva Respini, deputy director and director of curatorial programs at the VAG, and the exhibition’s curator. “She’s a historian and a time-traveller and a myth maker.” Báez has spent many years thinking and working through the deep-seated impacts of colonialism on the Americas and the Caribbean. Her work explores themes of race, gender, and identity, and questions established narratives of power and truth to show that “history is not fixed—history is fluid,” Respini says as she leads us through the exhibition, Báez in attendance.

Adjusting the Moon (The right to non-imperative clarities): Waxing, 2019–20. Photo by by Christopher Burke Studios. Courtesy of Firelei Báez and Hauser & Wirth, New York.

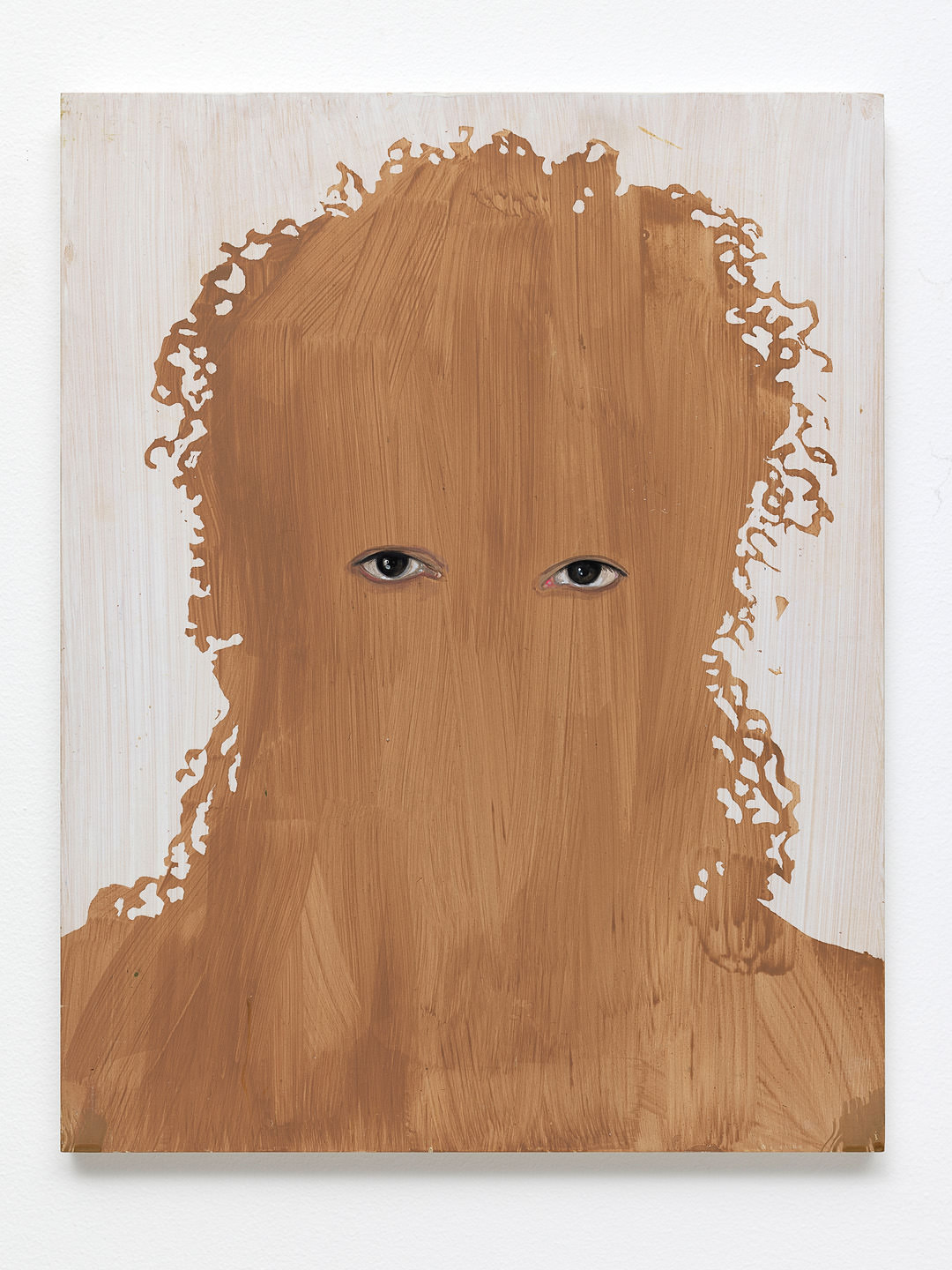

The exhibition, which is in roughly chronological order, opens with a room filled with Báez’s early works from the 2000s—mostly figurative paintings showing women in rich caramel tones. The largest piece is a multipanel painting of women’s heads, showing just the silhouettes of their hair and faces, but with their eyes clearly detailed, pinning the viewer in place with their gaze. The work is called Can I Pass? and is, as Báez describes, “a way of exploring bodily autonomy and access to different spaces.” She cites the “brown paper bag test,” which was a test used throughout the 20th century to enforce racial segregation of Black Americans. “It was used to determine who could have access to different social spaces, who could marry whom, et cetera. Depending on how close you were to that brown paper bag, that was your adjacency to whiteness,” Báez explains. She references similar practices in Latin America that enforced a type of racial caste system still in place today.

Thinking of the psychic violence embedded in these practices, Báez says she wanted to provide a generative space to the viewer, especially one coming from Latin America, to be able to see an interiority that went beyond all of that. “When we look at each other’s eyes, there’s so much that’s held within that. There’s expressiveness, there’s spirit, there’s emotion, that go beyond the microaggressions of reading someone down to the width of their nose.”

Can I Pass? Introducing the Paper Bag to the Fan Test for the Month of July (detail), 2011. Photo by Mats Nordman. Courtesy of Firelei Báez and Hauser & Wirth, New York.

As we walk into the next gallery, Báez underscores that most of her works intend to engage the viewer in some element of their creation and impact. Here, a sprawling collection of variously sized images comprises 225 pages of decommissioned colonial texts—about engineering, cartography, science—that she painted over in her signature bold colour palette. Both figurative and abstract additions are present: female bodies in motion, coloured circles, splashes of multitoned paint that recall the floral head exploding on the VAG’s façade.

She wants viewers to approach the works closely and intimately—to leave their breath on each piece and, in doing so, to contribute to its information.

“When I said earlier that she is a historian, for me this is an example of how she has intervened with history … in a sort of speculative way … with fanciful and sort of imaginative realms,” Respini says of these works. She notes that history books are a form of knowledge that has mostly been produced by white men, and that Báez’s work is not an erasure of this form of knowledge. “It’s in addition to,” Respini explains. “It’s a proposition for different ways that we might think about how knowledge is produced, the ways in which histories are produced, through books.”

When Báez first held the materials in her hands, she says they felt “almost like a treasure chest, being able to go into different periods of time and being able to articulate how that then makes our present.” She wants viewers to approach the works closely and intimately—to leave their breath on each piece and, in doing so, to contribute to its information. “I invite you, as much as you’re being enamoured by the mark, by the figurative gesture, to understand that you’re making this with me.”

As the exhibition progresses, the works expand in scope and physical scale, and so does Báez’s confidence in using even bolder colour and texture in her paintings, as well as more abstraction. Large canvases showing colonial buildings or maps explode at their centre with bombs of colour, thick with layered paint.

“Firelei is an incredibly gifted painter,” Respini says. “She is a history painter for our time. If you think about the European tradition of history painting, which is sort of capturing a moment and telling us something about the world, in very heraldic fashion, that’s what she’s doing with these incredibly imposing but beautiful paintings.”

This word, “beautiful,” is one that comes up in discussion as we near the end of the exhibition. Long scorned in the contemporary art world, “beautiful” art has been derided as unserious or lacking conceptual rigour. “When I was a student,” Báez recalls, “my professors were very much about Donald Judd, certain abstraction, certain withholding, certain chromophobia. So how do you hold that as a Caribbean person?”

Beauty, bright colour, figuration. All concepts that have historically been associated with the feminine and with a nonwestern Other. Báez’s work is a reclamation of them. An assertion that art can be both beautiful and lush and formally and intellectually rigorous.

Read more from our Winter 2024 issue.