What is the end product when a notoriously outlandish designer takes on something as staunchly traditional as a wedding gown? It could well be the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts’s freshly-opened Jean Paul Gaultier exhibition, Love is Love: Wedding Bliss for All à la Jean Paul Gaultier. Just as wedding gowns have been the traditional finale for runway shows (at least since the mid-20th century), Love is Love—on view through October 9, 2017—wraps up a 12-city international tour for the designer’s large-scale retrospective The Fashion World of Jean Paul Gaultier.

While the show’s other stops focused on a cross-section of Gaultier’s work with little bridal, Love is Love is strictly about matrimony—a theme heftily indulged in the layout, with a multi-layered wedding “cake” at the centre, elevating many of the designs. The craftsmanship alone gives Gaultier his grand finale, from the mind-boggling and myriad uses of tulle (including for a 23-metre train), to the sheer range of fanciful and yet dignified silhouettes on display.

Gaultier’s designs successfully break away from ideas of traditional marriage on a visual level. For example, La Mariée, from his Paris-Brest collection, features a large, circular front panel with a patchwork of woven feathers, grounded in Breton traditions. It eliminates the feminine demureness of a bridal dress, adding an assertive bulkiness. And Immaculata, a gown from the Virgins collection, may have a more traditional form, but the glimmering texture of its bodice feels futuristic, like something that an android bride could pull off (although ironically, there is historic imagery of virgins on the dress).

Individually the designs may be stunning, but it’s hard to reconcile what is on display with the exhibition’s apparent goal of taking a highly traditional institution and turning it on its head by being trailblazingly open. Another piece called La Mariée, for example, this one from Gaultier’s Tribute to Africa collection, could generously be called a fusion of African imagery with a wedding gown. But the dress, which features a large feather-filled mask dominating its bodice, ultimately feels surface-level. Putting aside the issue of reducing all of Africa to one “culture,” it doesn’t appear inclusive, or like something that people in any African country might wear. And another “La Mariée”, from the Hussars collection, is a dress featuring a lengthy feather headdress-train; it exhibits the same problems, although with indigenous North American culture.

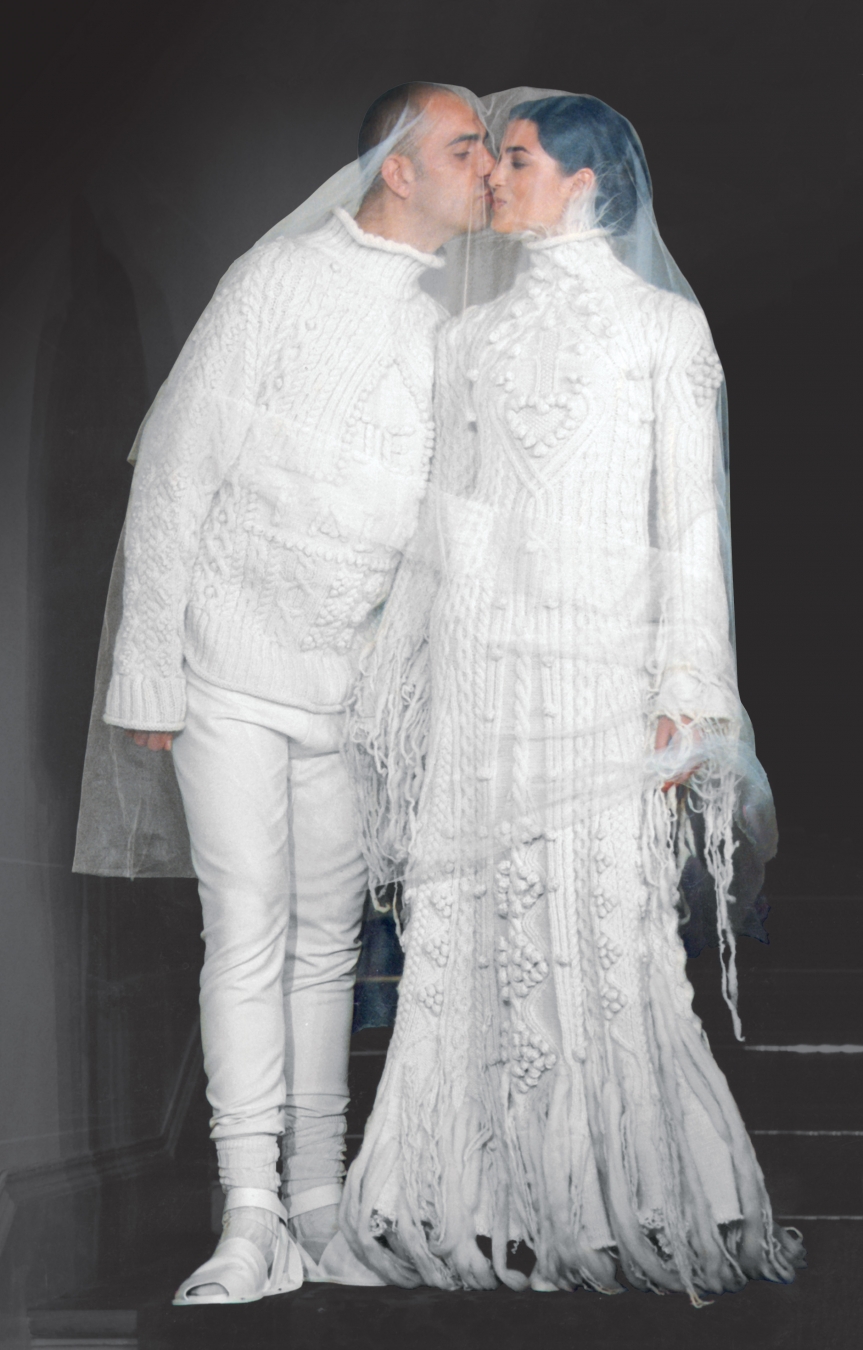

Well-crafted as they may be, the wedding dresses in Love is Love aren’t for all cultures, and they aren’t necessarily for all gender and sexual identities; with the notable exception of the wholly androgynous Joy Division ensemble, gender norms still underpin much of the exhibition. A lot of what is on display is coded feminine, even if it’s far from traditionally feminine wedding wear. At a time when queer ideas of gender (or sexual) fluidity are prominent, the “gay wedding” designs seem a little staid.

It feels like Love is Love is trying to have it all, being politically and aesthetically edgy, while still allowing for the audience to project their traditional wedding fantasies onto it. But it is a showcase of exquisite design nonetheless, and certainly gives viewers a lot to think about, perhaps asking more questions than it answers.