One of the defining moments of my fashion career happened in the Café de Flore in Paris. I had just turned down an assistant designer job at Sonia Rykiel in order to finish my studies at Écoles de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne (the famous Parisian couture school that counts Karl Lagerfeld and Yves Saint Laurent as alumni). I’d worked at Sonia Rykiel as an intern and then as a temporary design assistant, but I had decided that I would go back to school after my contract ended. Sonia had taken the entire design team for lunch, and while we were sitting upstairs (always upstairs, never downstairs), a man came over and whispered something in her ear. A short dialogue ensued, and I realized that Sonia was flirting with a man who had brazenly come over to our table to speak to her.

It was at that moment, sitting in one of the world’s most famous cafes, being bought lunch by a legendary designer who was well into her sixties and who was still getting chatted up, that I decided I should be starting my career, not going back to school. I accepted the assistant designer job and spent two wonderful years working for Sonia. The recent news of her death has caused me to reflect on those years and how she has influenced my career.

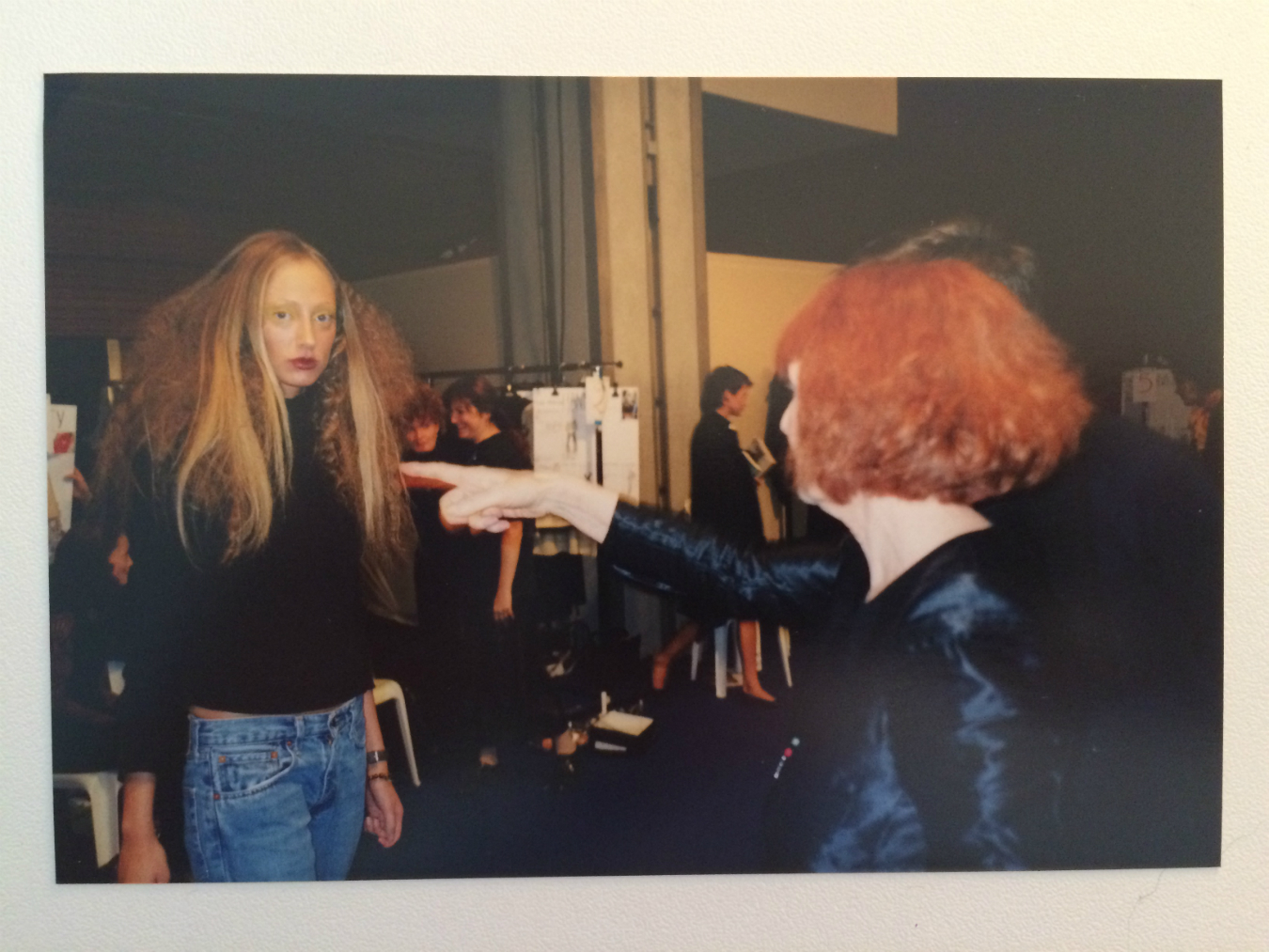

Like most successful designers, Sonia was very present; major collection decisions were never made without her, and she attended nearly all of the fittings. Unlike most successful designers, she was not a diva. She was mysterious and somewhat dramatic, but never overly pretentious. Sometimes she would walk into the room and it would take us a few moments to realize she was there, although I believed that the sneaking around was intentional—other times she would swan in, steady on her six-inch-high platform sandals, demanding our attention.

Her age meant we never did all-nighters (not even during fashion week), and as such I was free to blag my way into all of the parties and fashion shows. It’s said that the late nineties and early noughties were kind of a heyday in the fashion party scene in Paris, and I took full advantage. Those times seem so far away, not only because they were 15 years ago, but also because we didn’t have social media to document every single second.

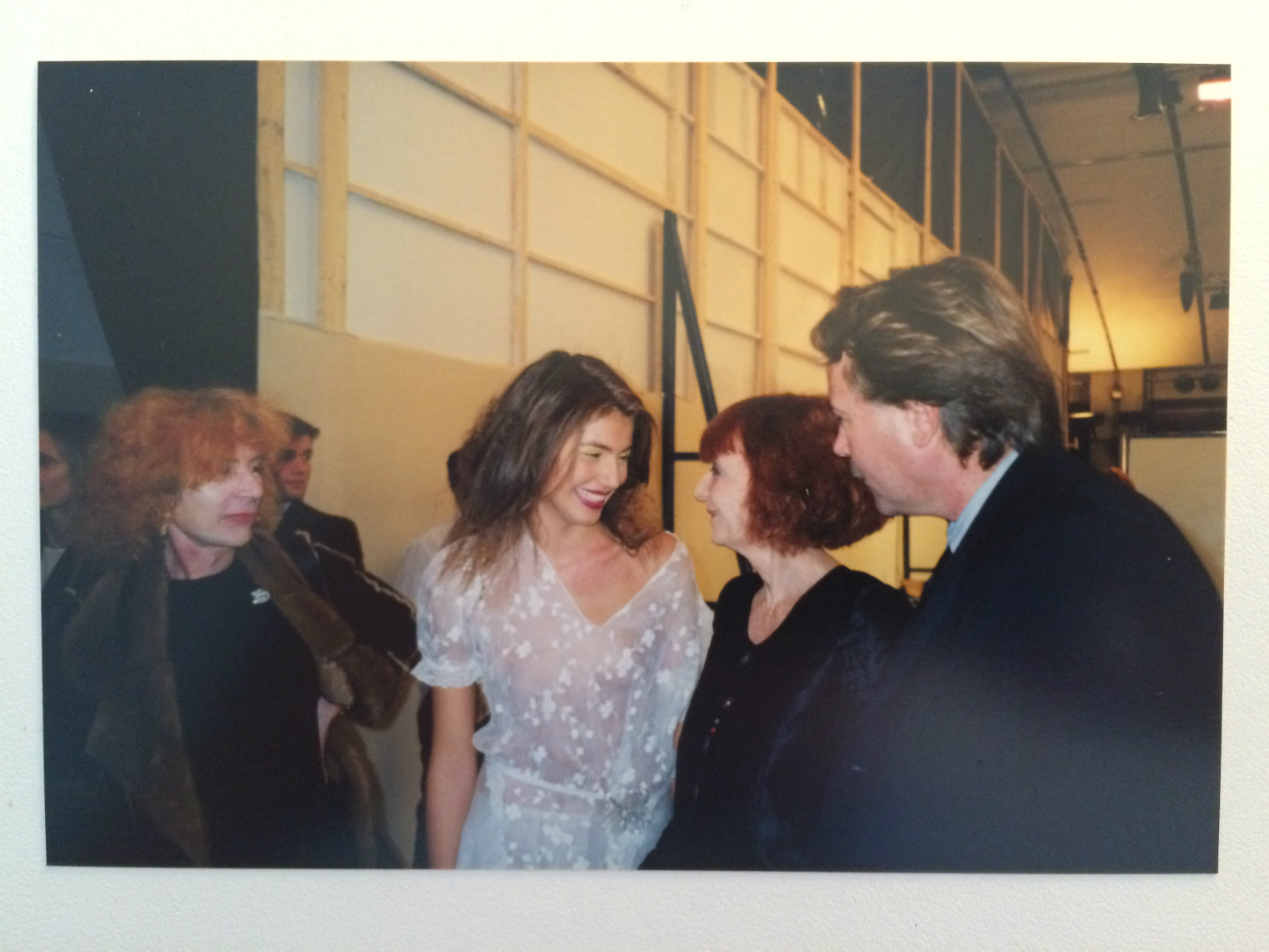

My life at that time was surrounded by people who went on to be stars. Carine Roitfeld used to style our fashion shows, sitting cross-legged in a chair looking at the fittings, making comments and popping tiny pills from a little box. Mario Testino used to shoot all of our campaigns—I often saw him out at clubs, and even attempted the occasional conversation with him. Lou Doillon, Jane Birkin’s daughter, came in and walked her first fashion show for us. She had no clue how to walk, and I had to show her the correct footing for strutting down the runway and turning at the end.

Unlike most successful designers, she was not a diva.

The studio was a revolving door of characters—very exciting for a 20-year-old from Vancouver—but it wasn’t the celebrities, the fancy clothes, or the supermodels that impacted me the most. I realize now that it was Sonia’s collections that have had the largest influence on my life.

Her collection plans are ingrained in my mind—notably, the repetition. It felt as though the brand mantra was “if it ain’t broke…” because fabrics and shapes that did well in collections never left. The wool-cashmere blend yarn, the jersey tailoring, the satin back crepe, the velour (made into jogging suits, long before Juicy Couture did them) were fabrics that were repeated season after season; our classic sweaters, cardigans, blazers, and tailored pants were in every single collection. This taught me that customers often like the same thing over and over again, with a few changes or updates. When I look at my own brand now, I can see that I’ve taken the same route, and it’s what has driven our business.

Her attitude towards fashion was also quite unique. In a city full of couture and fancy clothing, Sonia made relaxed knitwear and jersey suits that were incredibly chic but equally perfect for lounging on the sofa (probably a day bed, not a couch, if you are in Paris). She was designing the French equivalent of American sportswear: clothing needed pockets, things had to look relaxed, and comfort was as important as aesthetic. I think my love for the effortless was born there—none of her collections ever looked overly contrived, and the clothing needed to be easy. Sonia embodied the modern woman.

When she loved something, she fought for it. I remember in one collection we had a pleated crepe dress that the design team was ecstatic about. During a lineup, where models show the other departments the collection items (a rare act in fashion houses), the dress was vetoed by everyone outside of the design team. Normally Sonia would accept the veto and move on, but she insisted this dress stay. She added it to the collection as a press piece and it went on to be the best-selling shape that season.

When I look at my work today, it is obvious the influence she has had on me. I love making comfortable, functional clothing, but like Sonia, I won’t compromise on style. We could all take a page from her book—the book of a woman who managed to make head-to-toe knits look classy and not dowdy; a woman who gave her customers their favourite things, season after season; a woman who thought that clothing should always have pockets.

Alexandra Suhner Isenberg is the founder of The Sleep Shirt, a luxury sleepwear brand made in Canada and sold at Barneys, Selfridges, and Le Bon Marche in Paris.

Read more fashion stories here.