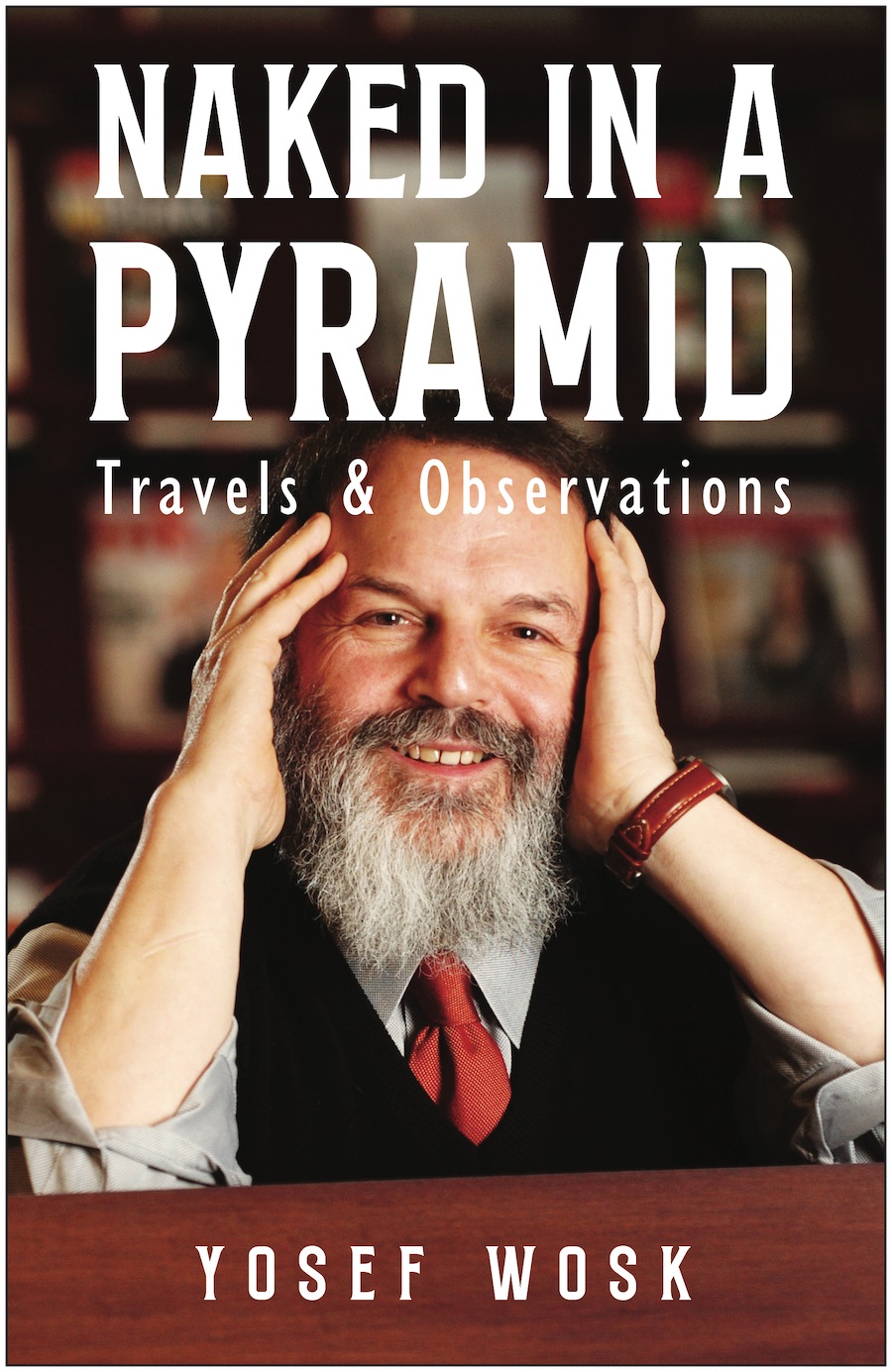

Seasoned world traveller Yosef Wosk grew up in Vancouver and has visited destinations from Mount Everest to the Dead Sea. When he signed up for a two-week voyage on a nuclear-powered icebreaker sailing from Murmansk to the North Pole and back, he hoped it would be the adventure of a lifetime. The trip didn’t disappoint. The essay below—excerpted from his new book, Naked in a Pyramid: Travels and Observations—offers a small glimpse into this memorable trip.

There is an old saying that I just made up: “Every detour leads to your true destination.” I had to travel to the ends of the Earth to discover not just the frozen polar regions but also some frigid regions of the heart.

I, like millions before me, imagined travelling to the North Pole but never thought that I could go that far. As I got older, and as my travels encompassed much of the world, I gradually began stretching towards the final frontier. At first it seemed impossible. Such expeditions were for governments or explorers, for researchers or madmen.

But my travels crept gradually north—seduced by the curve of the planet—until one day I woke up to the possibility of crossing yet another horizon and being at the still, turning point of the world.

***

Our ship, 50 Years of Victory, was the largest and strongest nuclear-powered icebreaker in the world. Driven by two nuclear reactors that produce up to 75,000 horsepower, it is 524 feet long and 98 feet wide. It can remain at sea for almost eight months and its nuclear fuel only needs to be replaced every four years. By the end of our two-week, 3,000-mile expedition, instead of burning 1,000 tons of heavy duty marine-grade oil, the ship used about a kilogram of uranium fuel and emitted no significant quantity of greenhouse gas. Of course, disposing of the spent uranium at a later date remains a delicate and somewhat controversial procedure.

50 Years of Victory was twenty years in the making. It was planned to be launched in 1995, to mark the fifty years since the end of the Second World War and the Russian victory over Germany in the Great Patriotic War. However, the chaos following the breakup of the Soviet Union, followed by a fire in the shipyard, delayed its commission until 2007. It was the first Arktika-class icebreaker to have a spoon-shaped bow, capable of breaking through ice up to 2.8 metres (9.2 feet) thick. Contrary to popular opinion, icebreakers do not ram their way through ice, forcing it to crack from horizontal pressure, but rather use a combination of forces, especially that of bearing down upon the ice-thickened seas with the weight of their double-hulled, steel reinforced bow.

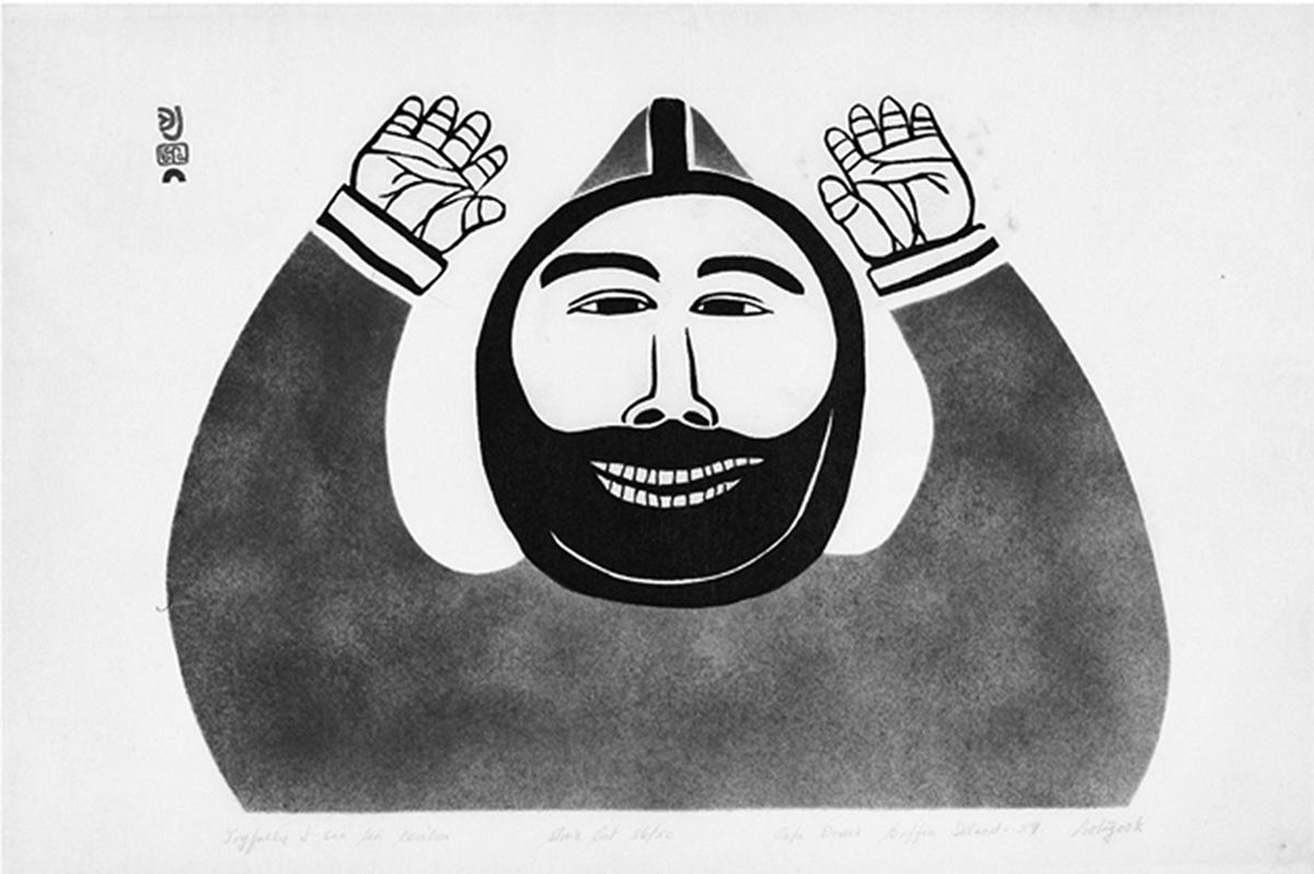

When an Inuit hunter spots a herd of caribou, this is the gesture he makes. Curved hands represent antlers, fingers correspond to the number of caribou. One’s body is turned in the direction of the prey. Print by Joseph (Eegyvudluk) Pootoogook (1887-1958).

Icebreakers attempt to follow open leads in the ice and navigate through paths of least resistance. Satellite technology has greatly enhanced this surveillance. Even so, the mighty ship occasionally came up against impassable barriers known as pressure ridges. On these occasions, the captain would follow one of two tactics: Either put the vessel in reverse for a few hundred metres and then ram forward with a determined blow, or reverse and search for a more amenable opening in the frozen waters, even if it involved a significant detour.

Victory and its sister ships are painted with a black hull and a bright international orange superstructure to make it more visible amidst the surrounding polar ocean and icescape. This is important for rescue missions in case of mechanical failures.

Originally built to clear a path through icebound waters for cargo ships following behind, or for scientific research or covert military purposes, the interior of Victory was later retrofitted to accommodate about 120 passengers for tourist cruises and to attract much-needed foreign currency for the Russian economy. The crew—from the captain to the kitchen staff—ranges from approximately 130 to over 200.

Our polar cruise was organized by a travel company that chartered the great ship from the Russian government. They provided all logistics and programs including a leader, guides, excursions, special programs and a full schedule of informative lectures by an assorted staff of international experts including a geologist, geographer, glaciologist, historian, biologist, ornithologist, and daily briefings from our expedition leader.

Excellent meals—always with a choice of menu and themed daily specials—were served in a dedicated dining room. Those who favoured alcohol were liberally supplied. Snacks were regularly available and afternoon tea, featuring fresh warm pastries, was welcomed. It was a comfortable but certainly not a luxurious cruise. Everyone pitched in to the best of their ability. Most were dedicated travellers on the trip of a lifetime safely ensconced in the floating metal ark. As for me, I was in geographic heaven.

There were various cabin configurations: Maddy’s and my room contained two beds, a desk and chair, a small closet, a modest bathroom with a shower in which there was hardly enough room to turn around, and two portholes that opened to let in fresh sea air. One had to remember, however, to lock them during turbulent days at sea. Room doors were never locked when we were out of the rooms. This somewhat surprising policy—one that aroused initial feelings of suspicion from this city dweller—served a number of functions, mostly relating to safety.

In appreciation of the 1958 print by Joseph Pootoogook: “Joyfully I see ten caribou.”

Before settling in, we were instructed to meet on deck, at the Muster Stations, for an emergency drill in case of any disasters such as a fire, collision, or a problem with the nuclear reactors. The ship carried covered lifeboats hoisted on cranes and equipped with provisions. We were assigned our numbered boats, crawled inside for a few moments to familiarize ourselves with how they worked, and were assured that we could survive floating in the frozen waters until rescued within a few hours or in a couple of days.

Victory carried an eight-passenger helicopter for shore excursions to otherwise unreachable areas and for flights over the vast icefields surrounding our ship. The onboard helicopter also assisted the captain with ice navigation and reconnaissance. It was kept tied down on a helipad on the back deck.

The ship also had a number of Zodiac boats aboard. These are small inflatable craft with an outboard motor that are typically used for ship-to-shore landings or short exploratory trips among fields of ice. Due to hazardous ice conditions and only one landing opportunity between Murmansk and the Pole, no Zodiac excursions were offered on this trip.

We did, however, have one helicopter expedition. That landing was in Franz Josef Land, Eurasia’s northernmost landmass. Nine hundred miles northeast of Murmansk and just over 600 miles south of the Pole, it consists of an archipelago of 191 flat-topped islands of varying sizes with steep basalt cliffs. No Indigenous population lives there; its only human inhabitants are Russian scientists and military personnel. It was the only landmass we would see on the entire trip as we sailed for two weeks through the Arctic Ocean.

It was during this portion of the journey that I took note of a quotation credited to an obscure author named Marie Le Fort:

After all, you need to be a bit possessed,

do you not, to journey to the ends of the earth,

finding nourishment in the sole idea of voyage?

As we were returning to Victory after that stopover in Cape Flora, Franz Josef Land, some of us were nearly seriously injured when birds collided with our helicopter’s rotors. The helicopter shuddered, lurched to its side and dropped before the pilot was able to bring it back under control just before hitting the water. He was able to get us back to the island for an emergency landing.

While the pilot eventually dared to return alone to the ship with the Sikorsky for repairs [it was grounded for the rest of the trip], we remained distressed and stranded on Cape Flora. We began to prepare ourselves to spend the night alone, with no shelter or food, on a desolate Arctic island. Although we put on brave faces, our minds began to flood with worst case scenarios. Radio contact was eventually made with the ship, however, and a few hours later a small rescue craft picked us up from a rocky landing. Relieved that we had survived a near disaster and celebrating our rescue, we were rewarded with a late supper of hot soup, broad bread and extra rations of vodka.

Excerpted and adapted from Naked in a Pyramid: Travels and Observations by Yosef Wosk (Anvil Press, 2023). Used with permission of the publisher. Read more stories about travel.