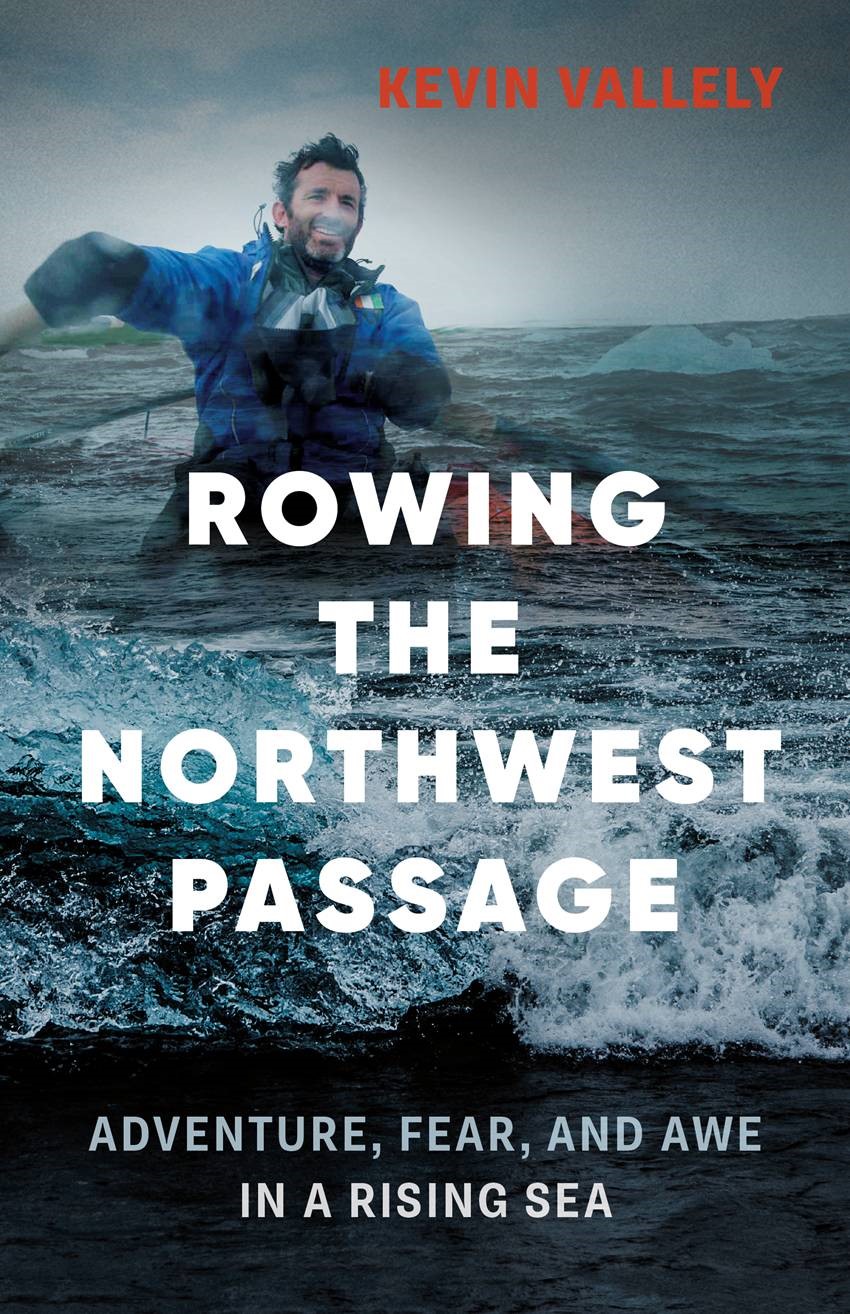

The following is excerpted from “Rowing the Northwest Passage: Adventure, Fear, and Awe in a Rising Sea” by Kevin Vallely (September 2017, Greystone Books). Condensed and reproduced with permission from the publisher.

Near disaster on Franklin Bay

As we round Cape Bathurst, the wind begins to build. It’s subtle at first, a light ripple across an otherwise glassy surface, but it grows quickly in force. The cape presents a vertical black wall of permafrost, which rises some fifty feet from water’s edge. A green carpet of tundra bends and tumbles from atop, its upper surface pulled seaward by the eroding bank. It’s an imposing sight—a shear icy wall extending into the mist, making retreat impossible if things turn bad. And they do.

The wind intensifies sharply, pushing us directly toward the cliffs. The water here is shallow and, as the seas build, so does the steepness of the waves. Soon whitecaps are everywhere. By the time we reach the most exposed section of the cape, the sea is in a frenzy. Waves find the shallow spots in the undulating shoals below and explode around us, washing over the deck. I’m watching all this from the confines of the cabin. The boys are still in their fleece from the nice rowing a couple of hours ago. The storm hit us so quickly they had no time to get into their dry suits. A fall overboard now would be catastrophic. Submersion in the icy water without a dry suit would mean almost immediate incapacitation, and a rescue would be very difficult.

As it stands, it’s taking all hands just to keep us off the cliffs. The boat is bucking like an angry bull and we can’t allow her to sweep broadside to the waves this close to shore. It’s Frank’s and my turn at the oars, and we make our seat changes one at a time, as quickly as we can. I replace Paul at the bow seat while Denis continues to row, fighting solo to keep us facing into the waves. When I start rowing, Frank replaces Denis.

We need to find shelter from the storm, but we won’t find it under those cliffs. We turn the Arctic Joule out to sea and start fighting. The waves and wind are pushing hard but we keep the bow pointed at forty-five degrees, facing away from shore, and after fifteen minutes gain a little breathing room. We turn the bow forty-five degrees back toward land and make good gains until the black cliffs loom over us again. We keep doing this, zigzagging in and out from shore, clawing forward as we can, until finally a foaming sand shoal presents an option. On the other side of the shoal are calmer waters. There appears to be one section of the sandbar where waves aren’t breaking as aggressively across its surface as elsewhere. I’ve lost track of how long we’ve been working, but Frank and I are worn out. We turn the nose of the Arctic Joule and make for the opening. I yell to the cabin to lift the rudder at exactly the right moment, and we scud across the sand and into protected waters. After tossing the anchor, I pull in the oars and head straight into the cabin.

“Good job, guys,” Denis says as we enter. “Way to keep it together out there. That’s class.”

It’s raining hard now and the wind is howling, but we’re in the cabin and out of the maelstrom. There’s not much room to fumble about and change out of our suits, though Paul and Denis aren’t fussed. The cabin is a terrible moisture trap and our wet gear isn’t helping. When all the hatches are sealed, there’s no ventilation, and it would be easy to imagine us falling off to sleep and never waking up. Fortunately, we can lock the two large hatches leading into the aft cabin—one off the deck and one off the top of the compartment—while still leaving a small gap to the outside. This is essential for the integrity of the locked door in the event of a mishap. The single biggest danger for an ocean rowing craft is to have water flood into the cabin and upset its balance.

Four months ago, an ocean rowing expedition traversing the Atlantic made international news after a rogue wave flushed through an open hatch into their cabin while the team was making a shift change. The wave capsized their boat and, once flipped, the boat wouldn’t re-right. The team was forced to deploy their safety raft and call for rescue. Fortunately, the water they capsized in was warm and cargo ships were plying nearby waters so a rescue was close at hand. A similar situation for us would likely prove fatal. There’s no marine traffic in these waters: any possible rescue would be days away. We have an emergency raft on deck and Mustang survival suits, but we’re not delusional about our situation. Donning a survival suit and then deploying an emergency raft requires considerable dexterity. Trying to do it in icy water where incapacitation comes rapidly is not a scenario we’d like to test.