The wind whistles through the wood panels of the old boat shed on the Tsawout First Nation reserve, and the smell of cedar cuts through the crisp air as master carver Carey Newman (Ha-yalth-kingeme) works on his tallest totem pole to date: an 11-metre carving for the home of a private buyer in Spain. Kneeling on a pad, he shapes a gentle curve, getting back in the groove after a whirlwind month. Less than two weeks earlier, Newman had been speaking with the Duke of Cambridge about art, reconciliation, and the Witness Blanket—the Kwagiulth artist’s arresting large-scale installation that depicts in agonizing detail the atrocities of Canada’s residential school system.

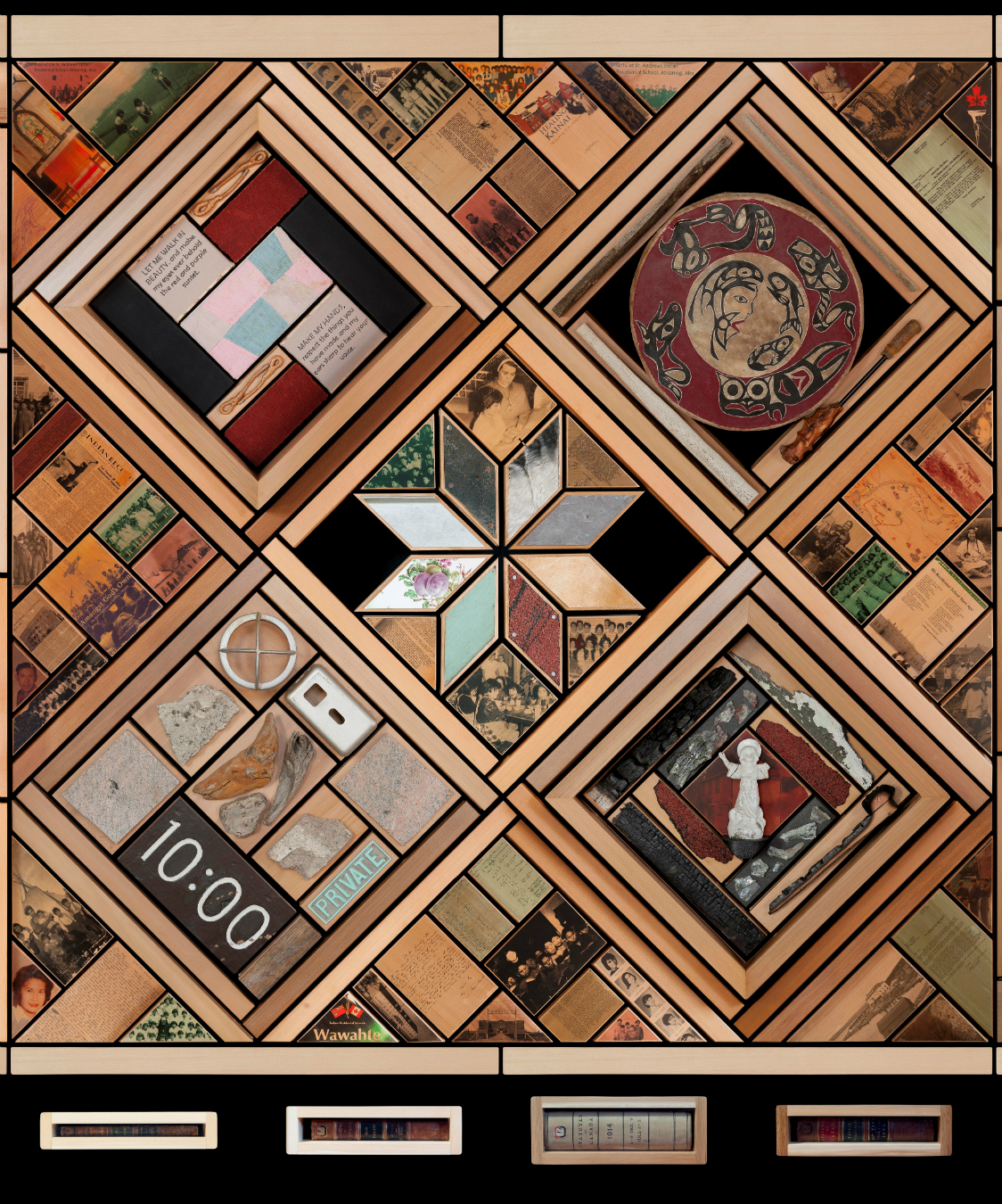

Newman continues carving as he recalls his brief meeting with Prince William at the reception hosted by the Province of British Columbia at Government House in Victoria. Like the other B.C. VIPs bumping elbows in the ballroom, Newman was allocated 30 seconds to speak with the man of honour (Kate was working the other side of the room). With the Witness Blanket on display at the event, Newman explained its purpose to the Duke: to stand in eternal witness to the effects of the residential schools. The blanket is as long as a city bus and contains more than 800 physical pieces of history collected from survivors, residential schools, churches, government buildings, and First Nations cultural centres across the country.

“The greatest impact of that entire experience was all of the conversation that it started,” Newman says, taking a break from the totem. “It brings that conversation around reconciliation into a bunch of different places, where it had limited exposure before.” Indeed, the British media featured the Witness Blanket in their reportage of the royal tour, alongside Grand Chief Stewart Phillip’s decision not to participate in a reconciliation ceremony at the reception due to lack of government action on First Nations issues. “I think we did a pretty fair job in this province of holding the conversation to account for the existing problems, and being welcoming and gracious hosts,” says Newman, who gifted Prince William a limited-edition book about the Witness Blanket—which features passionate, poetic forewords by author Joseph Boyden and CBC host Shelagh Rogers—as well as a tiny silver bracelet he made for Princess Charlotte that featured a thunderbird (representing strong will) within a hummingbird (representing beauty).

“This isn’t ancient history.”

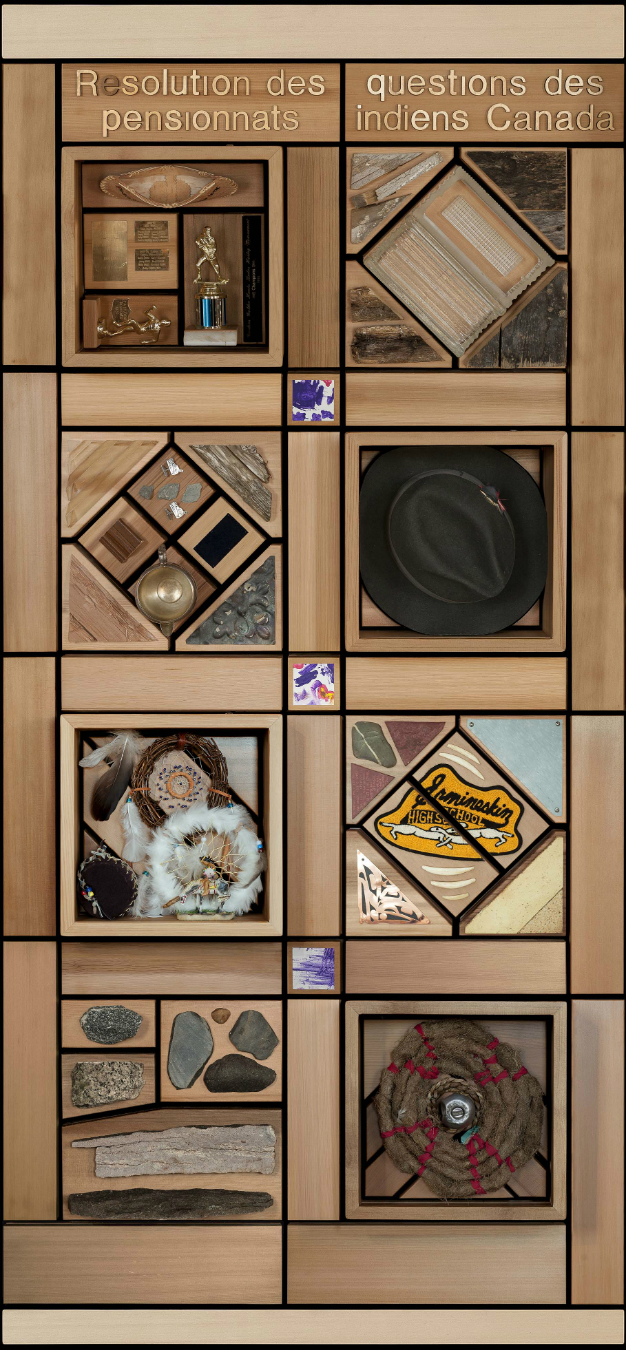

After zeroing in on a plastic hockey trophy, which was awarded in Saskatchewan in 1996 (the year the last school closed), the young man who was escorting Prince William at the party struck up a conversation with Newman. “I didn’t know it was so recent,” he recalls the attendant saying of the residential school system. “It’s pretty significant to make that connection,” says Newman. “This isn’t ancient history.”

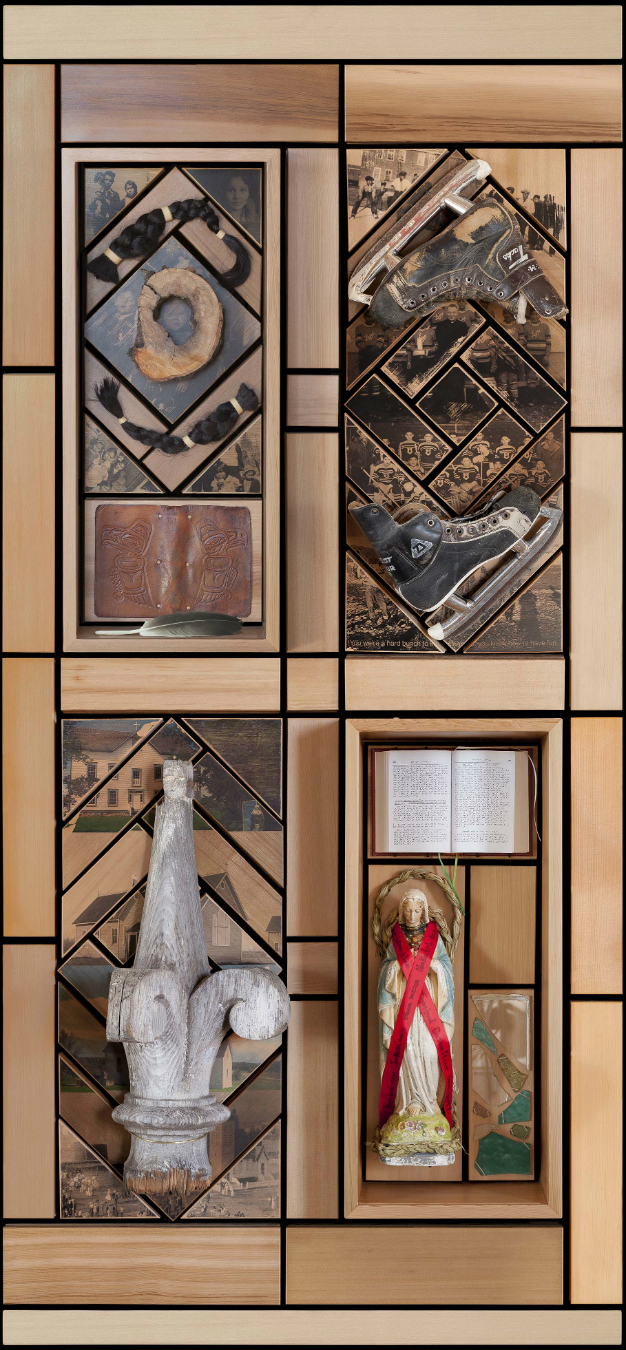

Sparking dialogue and building awareness are key objectives of the Witness Blanket, which was funded by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. For a year, Newman and his team travelled across the country, visiting 77 communities to collect artifacts and hear stories from survivors. A whip, proficiency badges “earned” by children, letters sent home by students, and a door to an infirmary were among the pieces of evidence gathered and later woven into a structure resembling a traditional blanket—a symbol of comfort and protection. It was Newman’s father Victor, a residential school survivor, who inspired him to create this ambitious work. Victor was kicked out of Saint Mary’s residential school in Mission after taking the blame for stealing ceremonial wine from the cellar with some friends and drinking it under an apple tree. When Newman came up with the concept for the Witness Blanket, the first thing he knew he wanted to include was a branch from that tree, which he later collected on a cathartic visit to the site of the former school with his family. In honour of his father’s hair being buzzed off upon arrival at the residential school—something that was done to “take the Indian out of the child”—his two sisters cut off their long braids, to be included on the blanket alongside the branch and a photo of their dad from his last Christmas at home.

Today, the once-painful tangible reminders of one of the most horrific chapters of Canadian history are doubling back across the country—this time unified together to show the strength and resilience of the communities—as the blanket tours universities and culture centres. Newman is also in the final stages of production of a feature-length documentary film with Victoria studio Media One, which he hopes will help the blanket reach an even wider audience. “If it takes seven generations to overcome the trauma that occurred, then it has to start with knowledge,” he says. “It doesn’t just disappear by the passing of time. It goes away through work, and part of that work is telling the truth and sharing it. The work of the blanket continues—it’s still opening people’s eyes to what happened, it’s still telling those stories.”

More from our Arts section.