West Vancouver Art Museum director Darrin Morrison describes the subject of the institution’s current exhibition as a “renaissance man,” and, standing in the midst of the homey gallery space, he’s surrounded by evidence.

Architect Fred Hollingsworth became a model airplane champion at 18 and later helmed a successful jazz band, dabbled in metal work and furniture design, worked at the Canadian Boeing plant during the Second World War, and, lucky for the West Vancouver Museum, kept meticulous personal records—all of this before becoming one of the pioneers of West Coast Modernism, an architectural style perfectly suited to the British Columbia environs Hollingsworth called home.

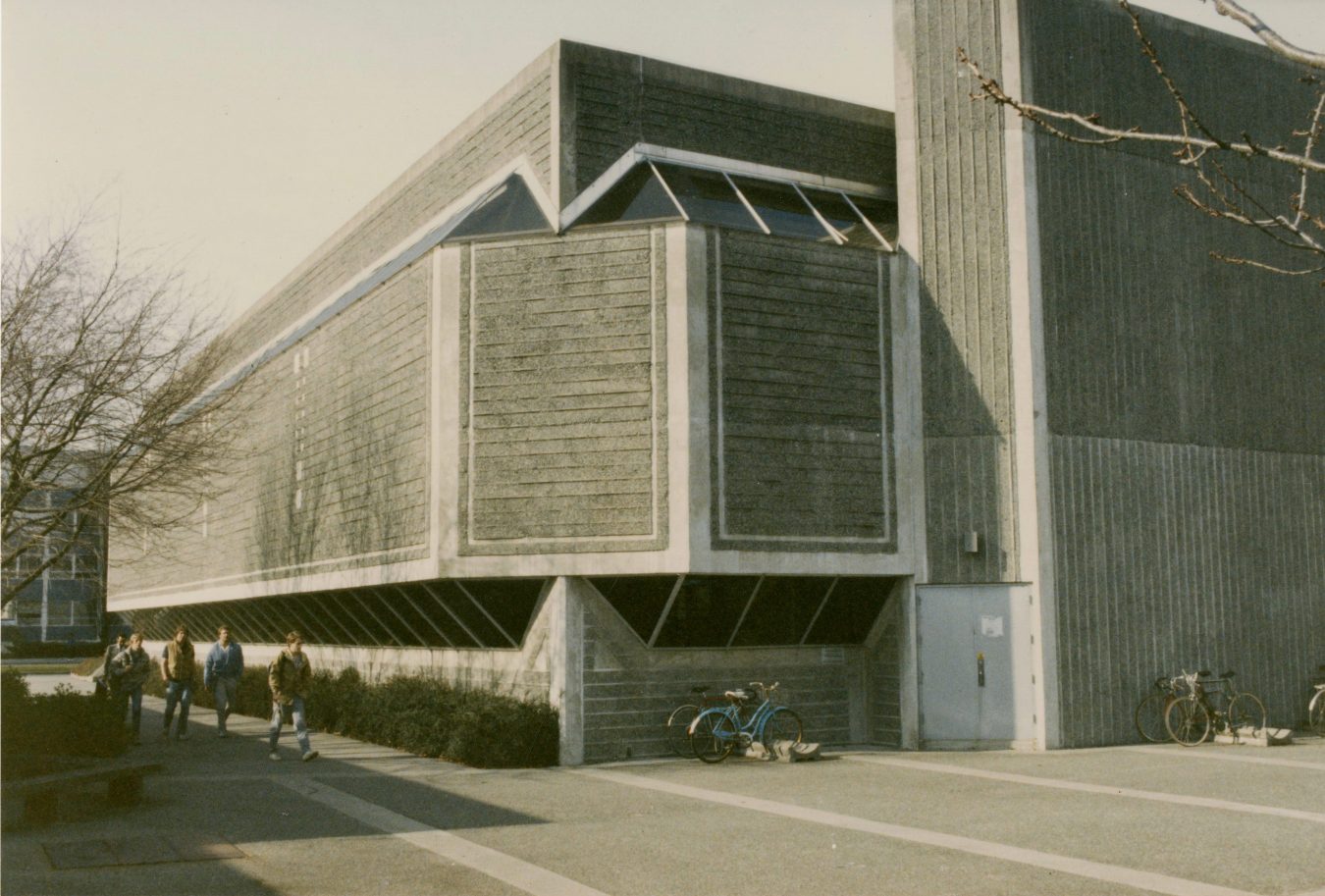

“Fred Hollingsworth: Art of Architecture” focuses on the remarkable cohesiveness of the architect’s vision. While he may have been a renaissance man, Hollingsworth—who died in 2015 at the age of 98—had a distinctive style from his very first design: a home he built for his family in Edgemont Village in North Vancouver. This airy, graceful style incorporated the landscape, from the enormous windows and earthy materials like concrete and wood, to the open indoor-outdoor spaces that invited contemplation.

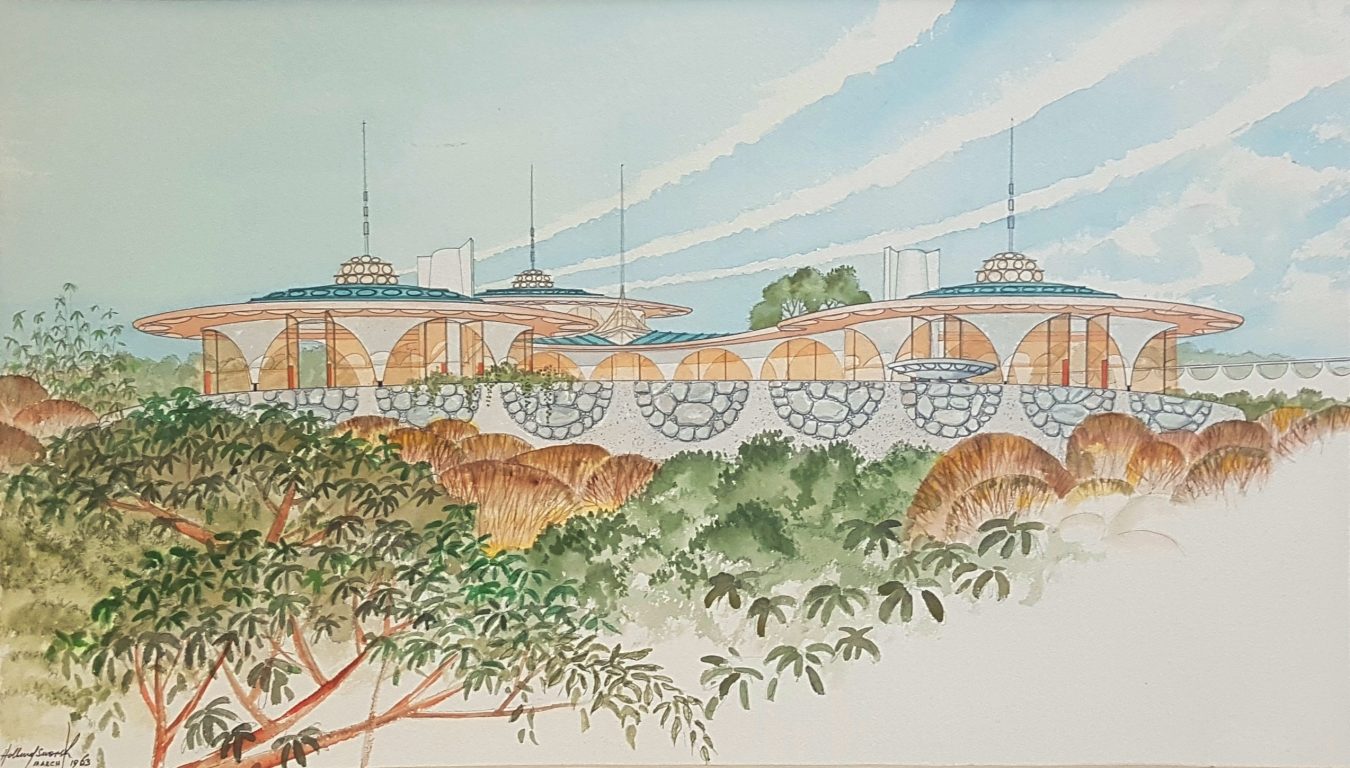

Hollingsworth created environments more than buildings, lavishing attention on details like light fixtures and dining sets in an effort to construct seamless living spaces. Several of these extra-curricular designs are on display at the museum, like desks and chimney fixtures, some next to hand-drawn plans or candid shots of Hollingsworth at work in his studio. It’s a powerful approach; showing the final product alongside the artist’s meticulous designs highlights his exceptional imagination.

He was a master draftsman, and rendered plans for clients in gorgeous two-dimensional drawings—many of them included in this exhibition. Without architectural models or software, he had to translate a monumental project into a series of intimate watercolours. This level of trust between architect and client is striking, and speaks to Hollingsworth’s innate affinity to accessible, eminently livable homes. To look at a drawing and be able to envision it as a home is a magic trick, and “Art of Architecture” (on until Dec. 22, 2018) portrays Hollingsworth as a deft illusionist, conjuring unique, personal buildings out of site, instinct, and inspiration.

Despite his lifelong success (Vancouver firm Thompson, Berwick, and Pratt hired him based on his first home design, and the great Frank Lloyd Wright was similarly impressed, offering him a job in the early 1950s), Hollingsworth remains lesser known than many of his mid-century modern peers. Not all of his designs are still standing (and not all of them were built in Vancouver), but there is nonetheless an effortless quality to his work that reads as a precursor to the sleek, airy architecture that’s still a hallmark of West Coast design today.

Speaking to this publication in 2011, Hollingsworth claimed, “I always thought that a house was the most important building I could draw.” It’s clear, walking though “Art of Architecture,” that the architect meant something more than most when he spoke of “a house.” His commitment to unified, stylish homes comes through—no detail is overlooked—but his respect for domesticity is even more impressive. His own life seems to have been so full that he must have expected the homes he designed to contain a wealth of experience; “Art of Architecture” shows a man whose life’s work was to make homes worthy of the lives they contained.

Design inspiration awaits.