With so many buildings in Vancouver these days, the cityscape is easy to skim. But every building—be it a fairy tale home fit for a hobbit or the tallest skyscraper in the British Empire—has its own story to tell. Each was written with an early vision, and evolved within the context of our city. The result is a rich mosaic of Vancouver’s settled history. Here are some architectural landmarks standing up for their times.

Sam Kee Building, 8 West Pender St.

The narrowest building in the world guards the western entrance to Chinatown. At only six feet wide, the Sam Kee Building was constructed in 1913 by owner Chang Toy. Prior to this, the City had expropriated 24 feet of the property to widen Pender Street. But the industrious owner decided to develop his lot anyway, based on a bet with a business associate. To maximize square footage, architects devised bay windows protruding above, and extended the basement underneath the street below. In the 1980s, new owner Jack Chow Insurance restored the historic building and added its own trademark neon sign. The fresh look attracted international notoriety for the skinny structure, and recognition from the Guinness World Records.

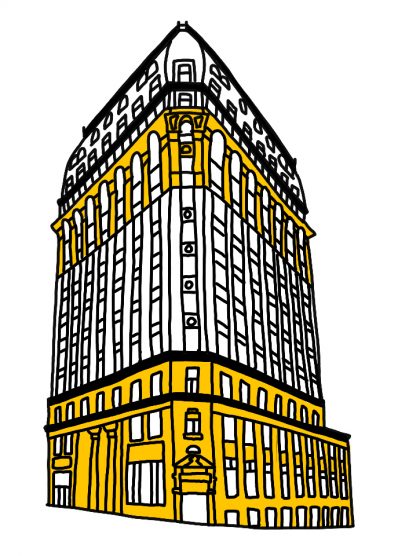

Dominion Building, 207 West Hastings St.

At 13 storeys, the notable red and mustard Dominion Building at Hastings and Cambie was Vancouver’s first “high-rise.” New building technologies and a real estate boom converged to bring the steel-framed tower—then the tallest in the British Empire—to fruition in 1910. It was a grand gesture during a period of economic and population growth for Vancouver. The Beaux-Arts building was grounded by granite columns and an open spiral staircase, and topped with a Parisian roof. However, the project proved to be too much for its developer, the Imperial Trust Company. The Dominion Trust Company—the building’s namesake—took over and completed construction, but also ran short of funds due to pre-war uncertainty and a subsequent recession. Although the hub of Vancouver’s financial district has moved westward, the eye-catching landmark remains poised today across from what is now Victory Square.

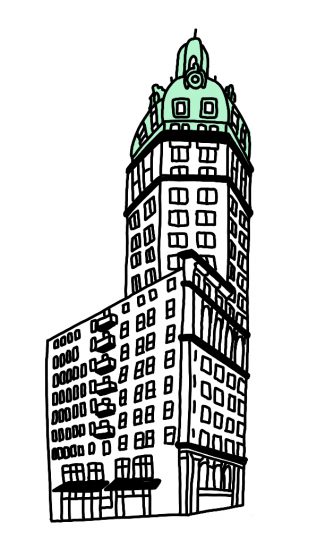

Sun Tower, 128 West Pender St.

Publisher Louis D. Taylor commissioned a 17-storey landmark to house his newspaper The Vancouver Daily World. The tenacious future eight-time mayor aspired to build an office tower that would trump the nearby Dominion Building as the tallest in the British Empire. The lofty goal was capped by a Beaux-Arts dome and cupola, and embellished with an infamous set of nine bare-bosomed maiden statues. Similar to the Dominion Building, the development turned out to be overly ambitious at the tail end of the early 1900s real estate boom. Not long after its completion in 1912, Taylor lost both the building and the newspaper. Ultimately, The Vancouver Sun purchased The Vancouver Daily World, and moved into the tower in the late-1930s when a fire destroyed its previous offices. The new resident installed one of the city’s most glaring signs—“THE SUN” in red neon, along with bright gold neon lightning bolts—ingraining the building’s new name into public consciousness. The Vancouver Sun relocated again in the mid-1960s and again in 2017, yet the building continues to be known as the Sun Tower.

Marine Building, 355 Burrard St.

In 1930, the 21-storey Marine Building was developed by a Toronto-based brokerage house as a home for the Vancouver Merchants’ Exchange. With its intricate art deco detailing and iconic references to historical ships at sea, the building instantly became a milestone. Just before opening day, The Vancouver Sun introduced the tiered structure in an eight-page spread as “some great marine rock rising from the sea, clinging with sea flora and fauna, tinted in sea green, flashed with gold….” Doormen welcomed patrons at the majestic bronze entrance, and women in sailor-themed outfits tended to what were at the time some of the fastest elevators in North America. Unsurprisingly, the elaborate project incurred sizable cost overruns. Once complete, the financially-troubled owner offered it at a deep discount as a new Vancouver City Hall. The City declined the opportunity, and the building was sold to the Guinness family. Today, the Marine Building distinguishes itself with timeless elegance in the heart of Vancouver’s business district.

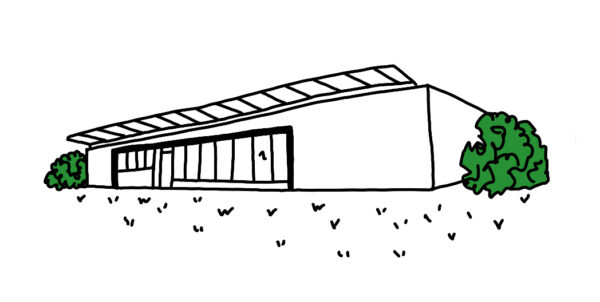

Binning House, 2968 Mathers Cres., West Vancouver

The 1941 Binning House in West Vancouver set the stage for the modern architectural movement in Canada. Celebrated artist, educator, and modernism enthusiast Bertram Charles Binning constructed this two-bedroom house for personal use. In adapting modernism to Vancouver during the war years, Binning sought to create a practical housing model with post-and-beam construction, a flat roof, and an open concept. Floor-to-ceiling windows integrated the interior into the sloped landscape with clear views across the inlet to the University of British Columbia. Foyer and exterior mural walls displayed Binning’s artwork. The Binning House became an important place for creatives to mingle and share ideas—Arthur Erickson, Jack Shadbolt, and Gordon Smith among them.

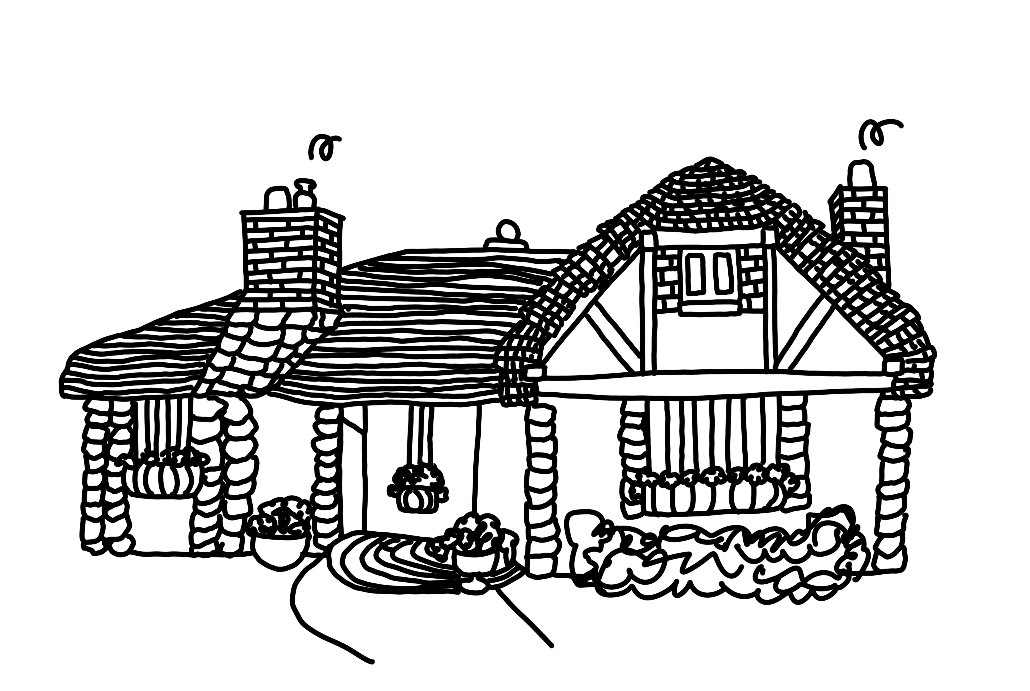

The Hobbit Houses, 3979 West Broadway; 587 West King Edward Ave.; and 885 Braeside Ave., West Vancouver

During the interwar years, storybook-style architecture reminiscent of medieval Europe and fairy tale homes began to appear in North America. The Lower Mainland’s best-known examples are the three “hobbit houses” built in the early 1940s in Vancouver and West Vancouver. Their distinctive wavy roofs, rubble masonry, and red brick chimneys are fanciful versions of English Cotswold cottages, and the three homes maintain their rustic charms to this day. Recently, the West King Edward Avenue rendition was in danger of demolition. Instead, it is undergoing a roof restoration and will live on as part of an adjoining townhouse development project.

B.C. Electric Building, 970 Burrard St.

B.C. Electric president Dal Grauer commissioned the modernist office building at Nelson and Burrard for the company’s headquarters. A proponent of progressive design, Grauer sanctioned a shallow diamond-shaped building to ensure that all employees sat within 15 feet of a window—a shape highlighted by the blue-green-black exterior mosaic by Bertram Charles Binning. Referenced by Architectural Review in 1959 as “the most gracefully handsome office building created anywhere,” it presided over the smaller, more conservative buildings of the time. With its dazzling evening lights, the building signalled the company’s success and the province’s bountiful resources. When B.C. Electric relocated in the 1990s, the building became Vancouver’s first significant commercial change of use, converting to a residential condominium tower called The Electra.

MacMillan Bloedel Building, 1075 West Georgia St.

The MacMillan Bloedel Building demonstrates Brutalist Modernism that prevailed in Vancouver during the late-1960s. Architects Arthur Erickson and Geoff Massey envisioned the distinctive Georgia Street tower for the Canadian lumber firm MacMillan Bloedel. The firm occupied 11 of the 27 floors during its heyday, before being acquired by a U.S.-based conglomerate in 1999. The building—with its raw concrete finish and deep-set waffle-iron windows—still stands tall like a great tree, personifying its original resident.

Westcoast Transmission Building, 1333 West Georgia St.

The dark-glazed cube building at West Georgia and Broughton was built in 1969 for the Westcoast Transmission Company. It was an avant-garde design for the firm’s downtown head office. Steel cables dangled 12 floors of office space from a central concrete core, leaving 36 feet exposed at the bottom for the building’s dramatic entrance. Lower floors were voided due to the weak commercial rent prospects in what was then a remote area. This “raised” tower profile preserved harbour views at street level (since obstructed with newer buildings), while suspension bridge-like dynamics delivered one of the most earthquake-resistant buildings in the city. In 2005, the structure was converted to a 180-unit condominium called The Qube.

Museum of Anthropology, 6393 Northwest Marine Dr.

For decades, First Nations tools and ceremonial objects were safeguarded in the basement of the University of British Columbia’s main library. In 1976, these objects finally found a permanent home in the Museum of Anthropology. Funds to construct the museum were gifted by the federal government to celebrate the 100th anniversary of B.C. entering Confederation. Situated at the University’s Point Grey cliffs, the museum was designed by Arthur Erickson, who was influenced by his fondly recalled image of a Haida village. Outside, Cornelia Oberlander’s landscape plan features indigenous plants and shrubs among two Haida houses, numerous totem poles by First Nations artists, and a reflective pool that provides continuity toward Burrard Inlet. Inside, the museum’s expansive ceiling and skylights give way to a series of galleries displaying thousands of objects from every continent, as well as Haida artist Bill Reid’s celebrated The Raven and the First Men, which depicts the legend of human creation.

Eugenia Place, 1919 Beach Ave.

A 37-foot pin oak tree (usually) sits atop a slender 18-storey residential tower at the foot of English Bay. Architect Richard Henriquez designed Eugenia Place in the late-1980s to pay homage to the actual height of the majestic old growth forest. Concrete stumps memorialize the trees that filled the area before English Bay became a densely populated urban setting. Meanwhile, the foundation and front steps trace the cabins and teahouse that initially resided on the land. The building’s recognizable pin oak tree made headlines in 2017 with its demise due to water restrictions, but not to worry: it is currently being replaced.

Waterfall Building, 1540 West 2nd Ave.

The Waterfall Building near Granville Island is named after its centrepiece: a recirculating waterfall. Inspired by Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation in Marseilles, with its “vertical city” arrangement and attention to communal space, the Waterfall Building invites the blending of public and private use. The complex is comprised of five buildings of six and seven storeys each—commercial spots at ground level, and live/work spaces above—all sharing a central courtyard and gallery. Completed in 2001, the design is evidence of Arthur Erickson’s penchant for concrete, while the steel balconies and staircases are a nod to Granville Island’s collection of repurposed tin factories.

Jameson House, 838 West Hastings St.

The Jameson House was Pritzker Prize-winning architecture firm Foster + Partners’s first residential tower in North America. Derailed for several years due to the global financial crisis, the project required a new development partnership in order to be completed. Once realized in 2011, the 35-storey tower combined residential, office, and retail space, and boasts Canada’s first automated parking system. The project also funded the restoration and preservation of two adjacent 1920s Beaux-Arts buildings—an integrated mix of past and present. Foster + Partners helped set off the contemporary wave of international architects shaping Vancouver’s skyline today.

This city is young by most standards, and cookie-cutter in a lot of ways—but sitting in plain sight, often missed as we rush from here to there, is a small bounty of historic buildings with stories to tell. Vancouver might not have Sagrada Familia or The Gherkin, but its architecture is powerful just the same. Like with most things here, you just have to take the time to stop and look.