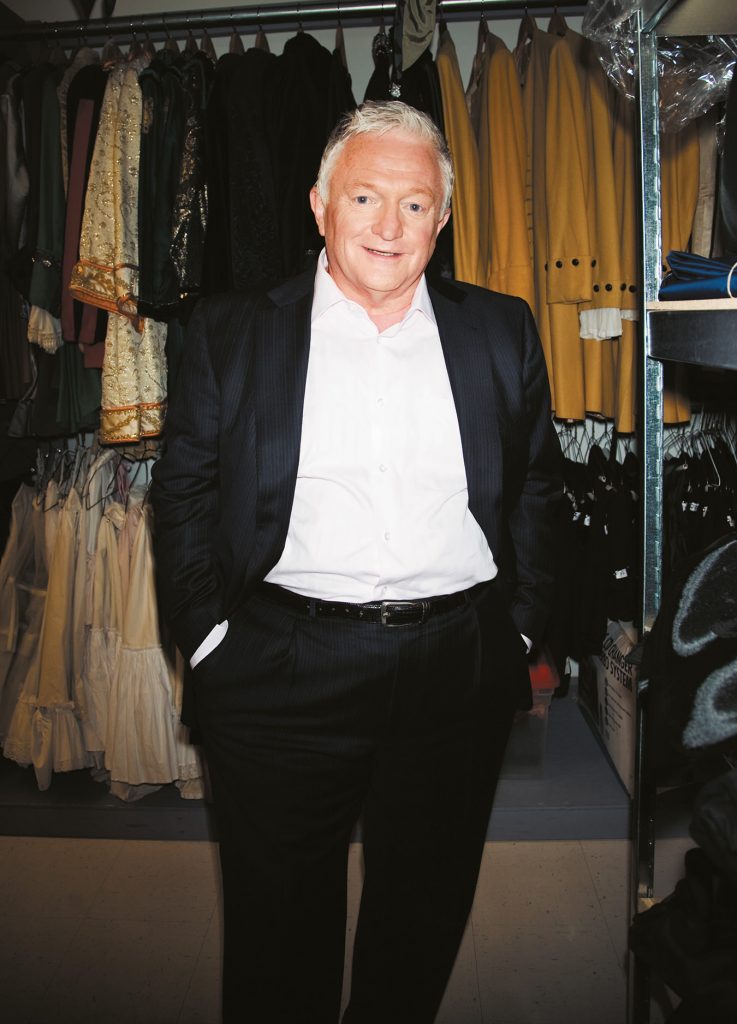

The Vancouver Opera offices on Cambie Street, downtown, are unassuming, except for all the fabulous promotional posters that adorn various walls. Productions past, present and future are represented, and they bear witness to the company’s history, now entering, remarkably, its 50th year. It is remarkable not only because the opera is flourishing in the 21st century in Vancouver, but because it is somehow hard to imagine the early days, launching a professional opera company in Western Canada and making a real go of it. Founded in 1958, and with its first performance in 1960 the Vancouver Opera has survived, and is stronger now than ever. That is thanks in no small part to the efforts and passion for the genre evinced by general director James Wright.

Wright performs both creative and executive roles, and from the beginning set the standard very high, for himself and all those around him, up to and including the artists. Taking a few moments from an always busy timetable, he contemplates his tenure: “I don’t really like to look back too much. We are always planning so far in advance. Still, I know that when I arrived there were two challenges I set for myself and the company. One was that I felt we needed our own fully dedicated music director. It took over two years, but when we found Jonathan Darlington, that was the beginning of a new era. We could say we have our own band. The buy-in from artists within our own community increased, but interest from the community as a whole grew significantly. The logistics of Jonathan not only developing our orchestra, but drawing interest from international-calibre conductors and artists to participate from time to time, were huge.”

For Wright, this is about how the opera is perceived in the community; a vital factor, since funding and support for the enterprise is not to be taken for granted, especially in times when public funding (i.e. governmental support) is on the wane. “The excellence of the music program helps fuel our fundraising efforts, in fact. People like to support something that is good.” He smiles, sits back, and relishes this point. Vancouver Opera is not operating as a charity case, or relying on support by people who simply believe opera should be a part of our cultural life. Rather, it garners support based on the calibre of the productions, its stars, its set design, the whole package. Although Wright does not want to go on record with a sweeping rationale for arts funding, he says, “I am happy to discuss the issues, one on one, with anyone, any time. But the focus has to be on working directly in the community.”

The second challenge Wright set for himself was exactly that: to ensure the Company occupies a “unique and vital place in the community”. He says, “It is important to show the relevance of the art form in the 21st century, to British Columbians.” To that end, there are educational outreach programs to schools at all levels, “to help teachers achieve their curriculum. We want to be relevant.” There are forums each year, based on the themes and issues of the four works on the calendar that season. There is Opera Speaks, linking opera to British Columbia, and the Young Artists Training Program. “Education beyond the theatre is one of our mandates,” says Wright.

With the able support of Tom Wright (no relation), director of artistic planning, who scouts the world for talent, James Wright notes that Vancouver Opera “builds the best cast possible, given our resources. The world is our talent pool. We consider Canadian talent first, but never at the expense of quality. Having said that, I can honestly say that using Canadian talent today means we do not have to compromise on quality. There are so many great talents out there.”

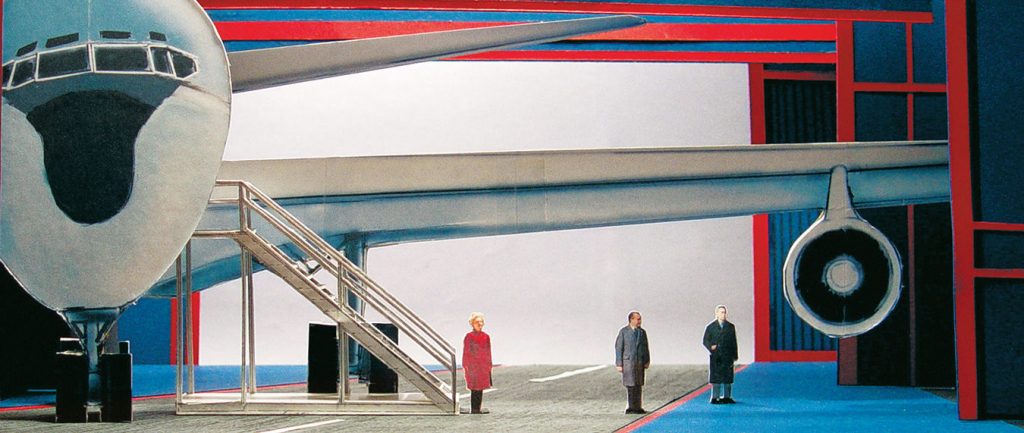

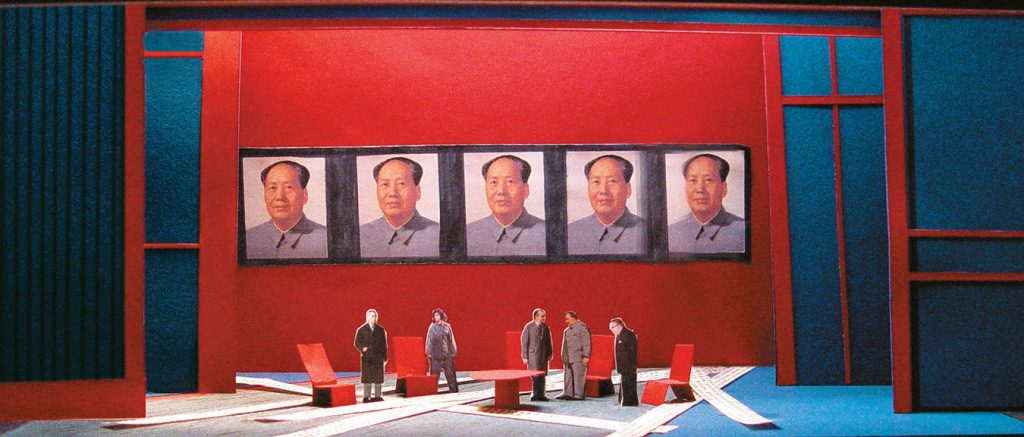

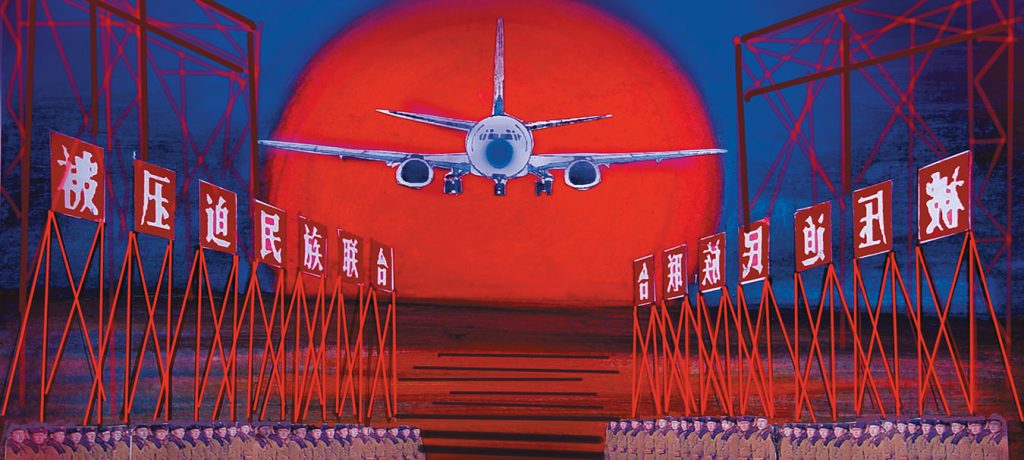

The repertoire itself, which changes from year to year, is part of an overall plan that encompasses a five to seven year period. “There are the classics, virtually a top 10 in the opera world, and we need to mount one of these each season. The snob in each of us may question, why The Magic Flute yet again? The demand is there, and frankly, it pays the bills, which enables us to venture out and try some new things, such as John Adams’s Nixon in China, which we will do this coming season.” It is a delicate process, of challenging an audience, and reiterating the grand themes and traditions, in a healthy blend.

Once a season’s repertoire is established, it becomes an issue of building the cast, deciding on approach, and determining what the budget will allow. “Who directs the production is absolutely crucial,” says Wright. And because, in relative terms, the Queen Elizabeth Theatre is a large one, and certain voices are better suited to it than others. It is, he says, a “constant honing” of the different aspects, to achieve the best production possible. “I look over an area of time, and avoid being repetitive and also avoid building a season that is too insular. Over the next six years, I want one post-World War II work each year, and to commission a work or even two. The problem is that contemporary works are always more expensive to produce, and tend to sell less well. So it is a double challenge. A work such as The Ghosts of Versailles can only be approached if we re-orchestrate it, to make it work for a big, regional company.”

It all seems to be working well. Last season’s closing two productions, Carmen and Salome, drew large audiences and rave reviews. There were even bloggers, invited on certain evenings, to record and report their experiences, and potentially open the idea of a night at the opera to a larger and younger demographic. It is all in keeping with James Wright’s understanding of the genre: “We do not curate. We open the doors to the community.” He concludes, quietly, that this is why opera remains vital. “Our responsibility is to keep reinvigorating the art form.”

Portaiture: Johann Wall.

Photography Assistance: Julie Jones.

Grooming: Tamar Ouziel for JudyInc.com, using TRESemmé Hair Care.