In 2006, Vancouver sculptor David Franklin Marshall died, leaving his unsold works and the contents of his studio in the care of his wife, Carel. The future spaces that will encompass this large body of material have raised some interesting questions for his widow and the other trustees of his estate today, but is a question of continued importance in the history of art.

In 1520, Roman Renaissance artist Giulio Romano inherited not only Raphael’s drawings, tantamount to the master’s thoughts on a page, but also his ongoing projects on which he was working at the time of his death. The studio contents of the great 18th-century British portrait painter Joshua Reynolds were dispersed to considerable fanfare, with a remarkable collection of Renaissance drawings eventually joining the collection of the British Museum. More recently, the Tate Museum in London controversially passed over the opportunity to acquire the chaotic studio of Francis Bacon. While this was London’s loss, it was Dublin’s gain: in 1998, the Dublin City Gallery acquired the contents of the studio and meticulously, even archaeologically, recreated Bacon’s studio in Ireland, which became an instantly successful tourist destination. Such scenarios are complicated not only by the nature of studio contents, immeasurably helpful to scholars and other artists, but also by the inclusion of the late artist’s works in the estate.

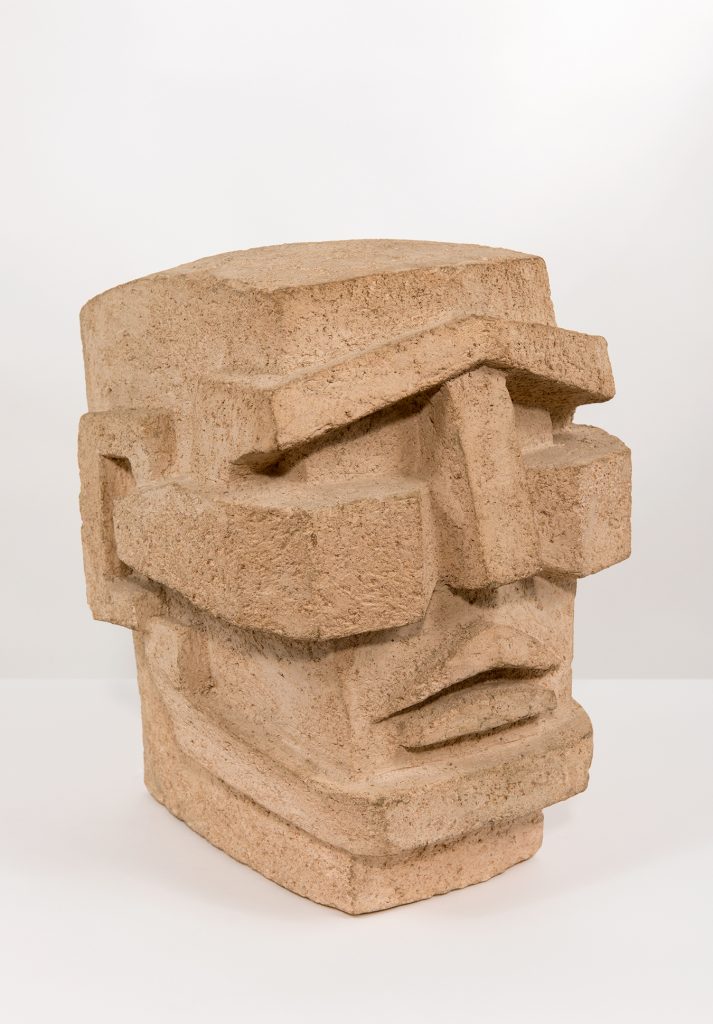

The contents of Marshall’s studio bear witness to his creative vision and display a loyalty to a modernist style that pervaded his sculptures from his early career in the 1950s until his death. The architecture of his studio, a simple garage with two large skylights, contrasts with the traditional wooden structure of the couple’s home, which they bought together in 1965. The skylights illuminate the two-room studio space and the white walls are offset by chartreuse-coloured double-doors. Shelves are filled with the tools of Marshall’s craft, while glass-fronted cupboards are home to innumerable plaster maquettes, models for the full-size sculptures that sit corner to corner on the floor of the studio. Made from regional stone, Carrara marble, poured concrete, patinated bronze, and rich fruitwoods, these sculptures, many of which are monumental in stature, stand cheek to jowl, like commuters on a packed train.

Shelves are filled with the tools of Marshall’s craft, while glass-fronted cupboards are home to innumerable plaster maquettes, models for the full-size sculptures that sit corner to corner on the floor of the studio.

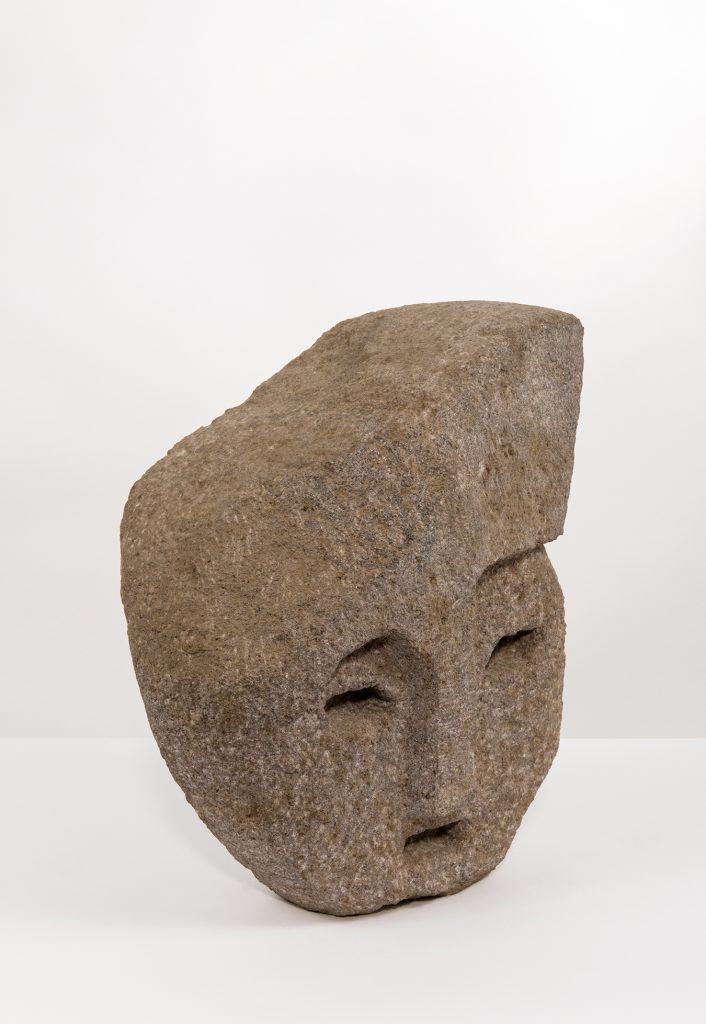

Born on a modest horse farm in pre-Depression Alberta, Marshall studied art at the Ontario College of Art from 1947 to 1949. Later, having hitchhiked across the country, he studied drawing and painting, at the Vancouver School of Art. He also studied ceramics at the University of British Columbia and sculpture at Heatherby School of Art in London, England. Following a serious accident, during which they were hit by an oil truck, Marshall and his wife used the settlement money to travel to Europe on a grand tour. An important stop on this trip was at the studio of English modernist sculptor Henry Moore. Moore’s influence is evident in many of Marshall’s works, especially in the carving of faces, but also in the way in which Marshall envisioned his sculptures to be displayed and collected. On his return to Canada, Marshall organized the first of many outdoor exhibitions of the sculptures of over 22 B.C. artists, thought to be a first in Canada, in 1956. He was instrumental in establishing a number of sculpture organizations in Canada and B.C., including the Sculptors’ Society of BC.

Beyond their trip to Europe, the Marshalls also spent some of their settlement money on their first few pieces of Inuit carving, acquired from the Canadian Handicrafts Guild of Toronto. The Guild, which was funded by government grants, bought sculptures from unnamed carvers in Hudson Bay, Cape Dorset, and Repulse Bay. These carvings greatly appealed to Marshall, who regarded them as artistic wonders made in the most extreme of environments. These sculptures are still in the Marshall’s house, at one point having been photographed and catalogued by the National Gallery of Canada for their own records.

Upon their return and settling in Vancouver, Marshall worked multiple artistic and non-artistic jobs, including at Eaton’s department store and teaching sculpture at Capilano College from 1973 until 1990. However, making sculpture was always the driving force in his life. According to Cliff Vicenzi, who cast many of his larger bronze works, Marshall was an absolute perfectionist. Vicenzi shared that he had never met a more dedicated and “workaholic” artist, who regularly maddened his neighbors with the noise of electric drills and sanders late into the night and was forced periodically to seek other places to work on his sculpture. Vicenzi observed that, while upholding the highest of expectations for himself and his work, Marshall was not arrogant, but always a pleasure to work with, trusting in the capability of the founder and his technical assistants.

And yet, despite his exacting standards and significant contributions to the arts in British Columbia, Marshall is not yet the household name that one might believe he should be. While a consideration of his long list of exhibitions from throughout his career reveals that he was always making and exhibiting sculptures, it is important to see that he had few shows at significant venues. Between 1975 and 1995, Marshall’s work does not appear to have been displayed, for example, at the Vancouver Art Gallery; instead he exhibited in many smaller municipal and some commercial galleries.

While upholding the highest of expectations for himself and his work, Marshall was not arrogant, but always a pleasure to work with, trusting in the capability of the founder and his technical assistants.

Marshall’s work, having been popular and well received within Vancouver and beyond in the 1950s and ’60s, appears to have become less fashionable in the 1970s. This shift seems to illustrate a change in tastes in Vancouver at this time, from modernism, the style in which Marshall worked, to conceptualism, wherein the idea beyond the work of art takes precedence over the aesthetic qualities of the art. Marshall’s vein of modernism was semi-abstract, engaging viewers in considering the subject while also demanding their admiration for the surface beauty of the work. While Marshall continued to work in this modernist style, the tastes of the Vancouver art world and its collectors turned to different styles and new local and international artists. Certainly, one of these new groups was the so-called Vancouver School, a group of conceptual artists whose work often used the tension between the city’s natural beauty and its grittier urban landscape.

It was not just Marshall’s style that detracted from his commercial and academic success. He was consistently hesitant to work with for-profit galleries and promote his own work. At gallery openings, Marshall would happily chat to friends rather than the collectors and influencers who could have significantly benefited his career. Suso Gygax, a Vancouver collector of Marshall’s work, said, “He was very keen to understand the latest scientific advances and I quickly learned of his fascination with geometric and mathematical principles that form the basis of his designs.” These interests translated into very technical sculptures, which appealed to technically minded collectors.

Thankfully, the eclipse of Marshall and his work appears to have been short-lived. His legacy is not yet finished, and his work is receiving a surge of renewed interest. His sculptural style, largely consistent throughout his life, complements beautifully the mid-century architecture and furniture sought after by residents of Vancouver and beyond. Newly erected in a space chosen by the VanDusen Botanical Garden, by the restaurant there, stand three Carrara marble sculptures by Marshall, which, as was sometimes the case, he never named. These took Marshall and his assistant, German Galdamez, two years to make: they are standing studies of curves and lines, greeting visitors, matched well by the geyser fountain in the pond beyond.

Craig Sibley, director of Vancouver’s Trench Contemporary Art Gallery, is the curator of Marshall’s work. He invited conceptual photographer Jeff Wall to look at Marshall’s works residing in his home studio, and Wall agreed. His first impression was encapsulated in his comment to Sibley: “How did we miss this?”

In surveying Marshall’s sizable corpus of significant works, one is struck by the patterns that emerge, like forms that echo again and again, in different sizes and materials, but which are fundamentally rooted in the same shapes and planes.

Wall worked to document the space filled with Marshall’s works. The results of his visit accompany this article, and they are not the typical product of this photographer’s artistic process but true and accurate reflections of Marshall’s sculptures and the environment in which they were conceived. These photographs contribute to Marshall’s tangible legacy, one that stretches beyond his works and even his role as organizer of sculptural groups and exhibitions. They work to document Marshall’s contribution to 20th-century Canadian art. The works themselves are on display at the Trench gallery for a limited time, until the end of October.

In surveying Marshall’s sizable corpus of significant works, one is struck by the patterns that emerge, like forms that echo again and again, in different sizes and materials, but which are fundamentally rooted in the same shapes and planes. It is not uncommon for sculptors to make the same form in different sizes and materials, which demonstrates their versatility and, in Marshall’s case especially, speaks to a quest for perfection. His sculptures possess a timeless quality, and a viewer’s response to them is immediate and visceral. His works demand viewer engagement but do not necessarily require a specialist knowledge to appreciate them.

An early work, Injured Fireman, made from poured concrete, has stood in Marshall’s garden for decades, overshadowed by a lush tree. The figure holds his disproportionately large hands out in front of him, matched in size only by his cavernous eyes. The sculptor modelled the form on a fireman he had witnessed leaving a burning building, while riding the bus home on an ordinary evening. The fireman had scorched his hands and was in a state of shock. The exaggerated size of the eyes and hands of the sculpture communicates the fireman’s pain and state of mind. However, their size also serves to emphasize the priority that an artist might place on these particular body parts: Marshall needed both his hands and his eyes to create his sculptures.

The works from throughout his life emerge as a series: the hallmarks of the over-life-size sculpture of Injured Fireman from 1957 are visible in his six-foot-tall maple carvings from as late as 2002. While his consistent style may have hampered him in the short term, as is so often the case for artists, his adherence and loyalty to the modernist style will work in his favour in the long term. It is his devotion to this single style that grants his work a timeless quality that will continue to appeal to collectors of his work long into the future.

For Carel, his widow, however, the many sculptures that stand in his studio and adorn their garden represent a lifetime past and a future of uncertainty. Looking over the finished sculptures, she remembers when the great logs of unworked wood and blocks of Italian marble and local stone were delivered to their house. As Carel surveys the contents of the studio, she says simply, “So many beautiful sculptures.” By all accounts, Marshall was deeply protective of Carel throughout their life together, rescuing her at the beginning of their relationship from her overprotective mother, nursing her back to health after their awful road accident, and taking her hand when in public, even in their later years. It seems cruel that she is now faced with the significant and very daunting task of overseeing the eventual dispersal of his work after his death. It is her fervent wish that his sculptures find deserving homes with new appreciators. As with any series of patterns, the future displays of Marshall’s works in new environments will doubtlessly evoke novel resonances and variations.