In 1906, Jeremiah Crowley followed the gold rush to Vancouver from Newfoundland hoping to get rich, leaving behind a career as an ironworker and looking toward an uncertain future. Upon arrival, he discovered he had missed the rush entirely, and finding himself a stranger in a strange land, decided to buy a small farm with six cows he planned to turn into a dairy. He named it after the peninsula he left behind in Newfoundland: Avalon.

Despite an enormous shift in the industry and many ups and downs, Avalon Dairy thrives today at 115 years old and counting, the longest continually operating dairy in B.C. It did not gain that impressive title without a fight. The early years of Crowley’s enterprise were fraught with difficulty. Dropping milk prices and an economic depression forced him to sell his cows at auction in 1918. Foreclosure threatened his land in 1924. It is out of these struggles that Crowley finally decided to purchase his milk from other farmers and switch his focus to operations as a dairy rather than as a ranch dairy, the same basic model that exists at Avalon today.

After finding his footing again, Crowley decided to convert Avalon to pasteurization. His economic situation didn’t allow for the expensive equipment required, so he decided to make his own. Crowley’s first attempts failed, but eventually he was able to fine-tune his work, and even sold his pasteurizers to other dairies.

Crowley bottled his milk in the thick-lipped glass jugs still in use and delivered them via horse and wagon. In the early years of Vancouver, Crowley’s cart was full of sounds, sights, and smells that today exist only in memories: the clop of hooves on tamped dirt roads and cobblestones, the smell of horses and the clank of bottles placed carefully at doors.

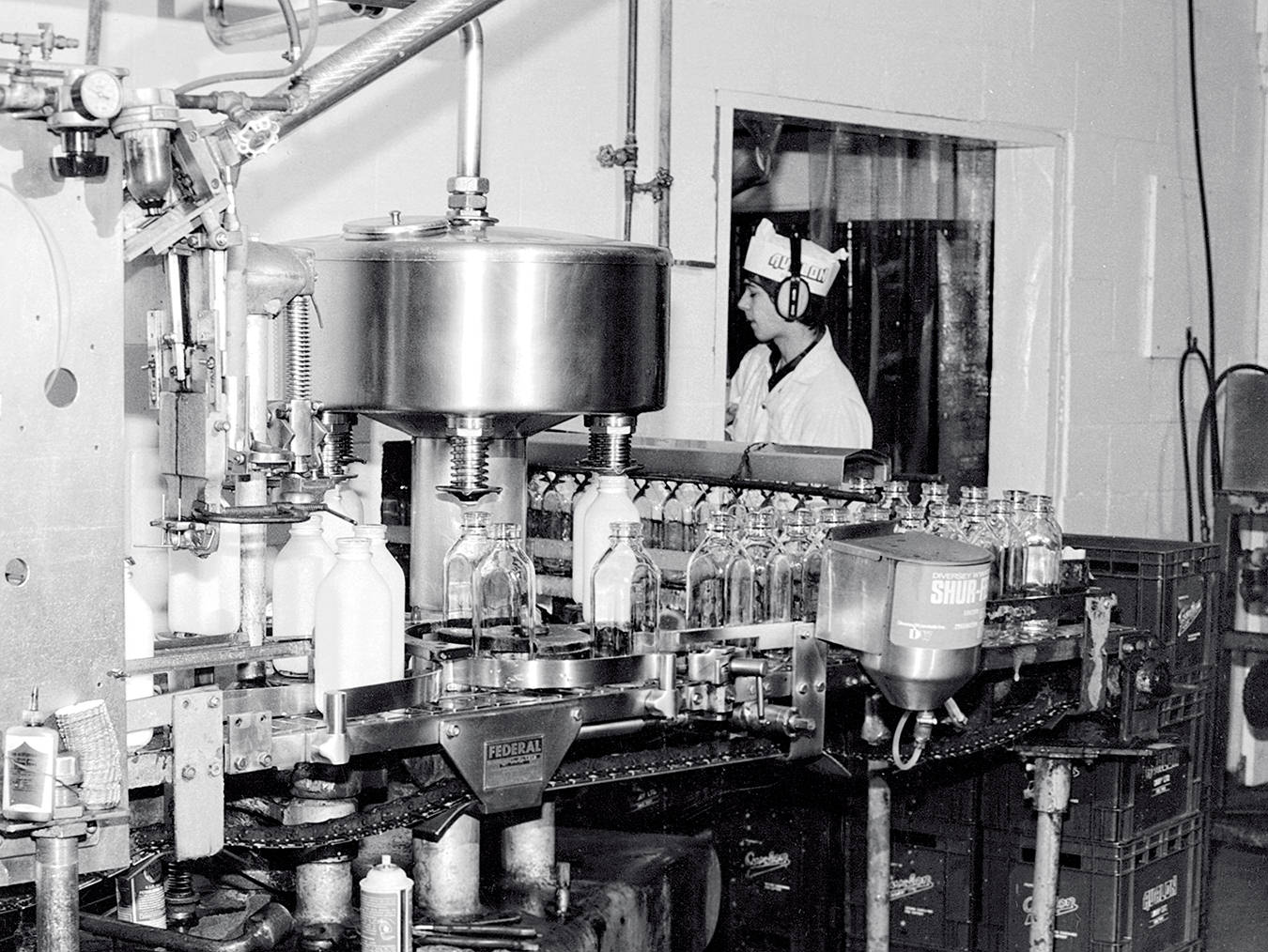

Photo by Dennis Gocer/The Collective You.

Crowley’s no-nonsense approach to his dairy business is reflected in an early Avalon flyer, distributed to the homes of his customers: “We also take this opportunity of informing you that our method of business is in no wise injurious to our competitors, as we do not employ canvassers to make insinuating and misleading statements. But only sweet, fresh milk in clean, sterilized bottles, delivered by competent, courteous men; from choice, healthy, clean, well-fed, tuberculin-tested dairy cows.”

Things began to look up for Avalon during the onset of the Second World War, when Great Britain looked to Canada for dairy products and provided subsidies for it, allowing Avalon to prosper after years of adversity. Following the war, the dairy landscape began to change, and larger corporate dairies began buying up smaller, independent operations—there were hundreds in the Vancouver area alone. Avalon held strong to its independent status and renovated its operations. By 1966, despite the death of Jeremiah, a fire that destroyed the barn, and the ever-looming threat of conglomeration, Avalon was the last of its kind standing.

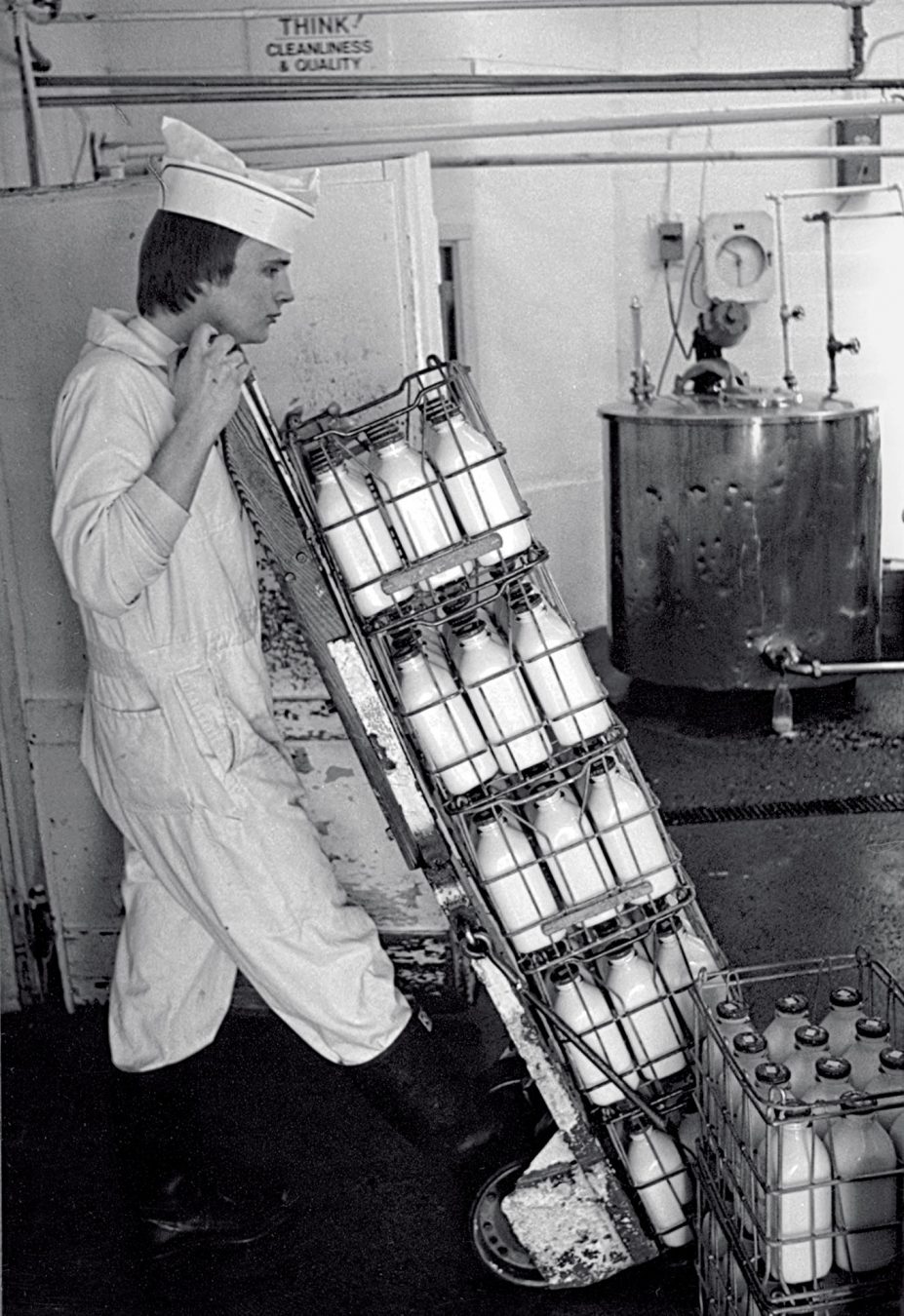

Photo courtesy of Avalon Dairy.

Avalon succeeded by having a strong sense of itself in the landscape, high standards, and an outright refusal of factory farming. The dairy was the first adopter of an organic product line in B.C. In 1995, CEO Gay Hahn led the charge to incorporate organic products into Avalon’s line, seeing how well it fit with Avalon’s values; today organic represents 95 per cent of the dairy’s offerings.

With the rise in popularity in recent years of local, farm-to-table foodstuffs, Avalon has found a renewed footing, and is now reaping the benefits in a newer, larger facility in Burnaby and with chains of distribution as far reaching as Hong Kong. Avalon currently produces over 6 million litres of milk a year and its organic products have no GMOs and are carefully controlled from the soil, to the feed, to the manufacturing processes. The dairy offers cream, milk, chocolate milk, hand-cut cottage cheese, buttermilk, cheese, butter, sour cream, yogurt, eggs, and ice cream. The high quality is reflected in longer best-before dating times (21 days versus the industry average of 18) and sumptuous, 36 per cent whipping cream sought after by the city’s chefs.

Photo by Dennis Gocer/The Collective You.

Three generations later, the Crowley family still runs Avalon—Jeremiah’s grandson Lee is the owner—and employs a small staff of 26 to run the dairy 18 hours a day, seven days a week. Jeremiah’s original farm has earned a Heritage Designation from the City of Vancouver, itself only 20 years older than Jeremiah’s enterprise.

The iconic glass bottle that still distinguishes Avalon’s line from the rest of the marketplace has been around since 1915, and as with other elements of the Avalon story, it has not persisted without a struggle. The glass bottle survived a switch to metric in 1977 but ran the risk of discontinuation after a tax imposed by the provincial government in 1983. Avalon’s customers responded with 6,000 signatures to remove the tax, and two years later the bottle was back housing milk and cream as usual. Avalon pushed for its glass bottle not only for the nostalgia but because milk in glass bottles stays cooler, fresher, and lasts longer.

Vancouverites of varied ages and neighbourhoods remember Avalon’s home milk delivery keenly (a service that is still available in Victoria and Salt Spring Island), particularly being the first of the family to loose the plug of rich cream that rose to the top of each un-homogenized bottle. It is this familiarity, in addition to innovation and quality that has allowed Avalon to endure as a Vancouver institution, an indelible part of the fabric and legend of our city.

This article from our archives was originally published in our Autumn 2014 issue, and updated on April 30, 2021. Read more local history stories.