When the National Gallery of Canada came knocking with an invitation for Steven Shearer to show his work at the 2011 Venice Biennale, the artist hesitated. Shearer—tall, lanky, and much younger looking than his 43 years—never expected to travel the world as an internationally recognized artist. As a teenager, he sequestered himself in his parents’ Port Coquitlam basement, growing his hair long, playing guitar and listening to heavy metal. To this day, Shearer retains that reticence. He is soft-spoken, he chooses his words carefully and he is very seldom photographed. It poses the question: you can take the boy out of the basement, but can you take the basement out of the boy? Perhaps that’s why, on the eve of the art world’s largest coming-out party, Shearer seems unfazed by the attention.

Representing Canada at the Venice Biennale is a privilege that has been bestowed on some of Canada’s most pre-eminent artists: Rodney Graham, Mark Lewis, Rebecca Bellmore and David Altmejd, to name a few. And thanks to a little arm-twisting, Shearer will hold the 2011 honours. “I realized it’s not an opportunity that’s going to be based on you being ready,” he says.

But this is a pace that is familiar to Shearer as of late; in fact, it is representative of the steady rise in interest in his work. Rewind to a few years ago, to 2009’s Art Unlimited exhibition at Art Basel, Switzerland. The market was bottoming out, dealers were scrambling for sales and it seemed New York galleries were readying for the apocalypse—yet collectors were clamouring for Shearer’s work.

“It’s one thing to generate success and build a studio, and another thing to not be distracted by it.”

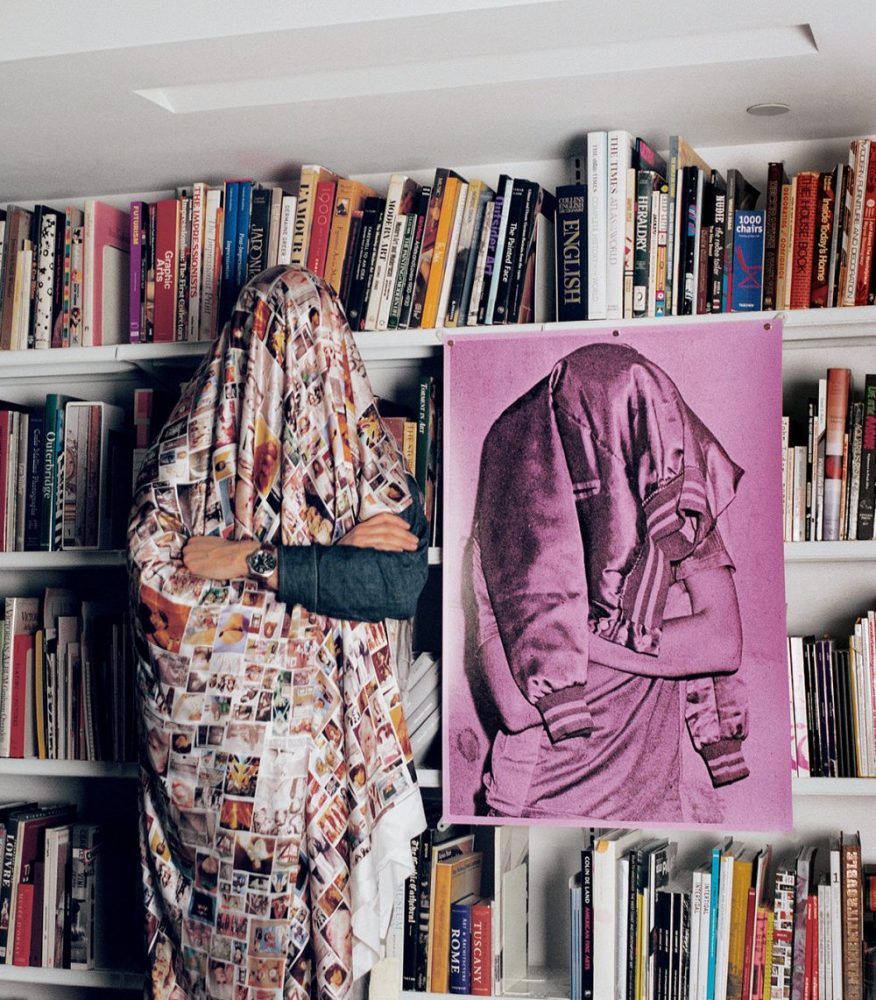

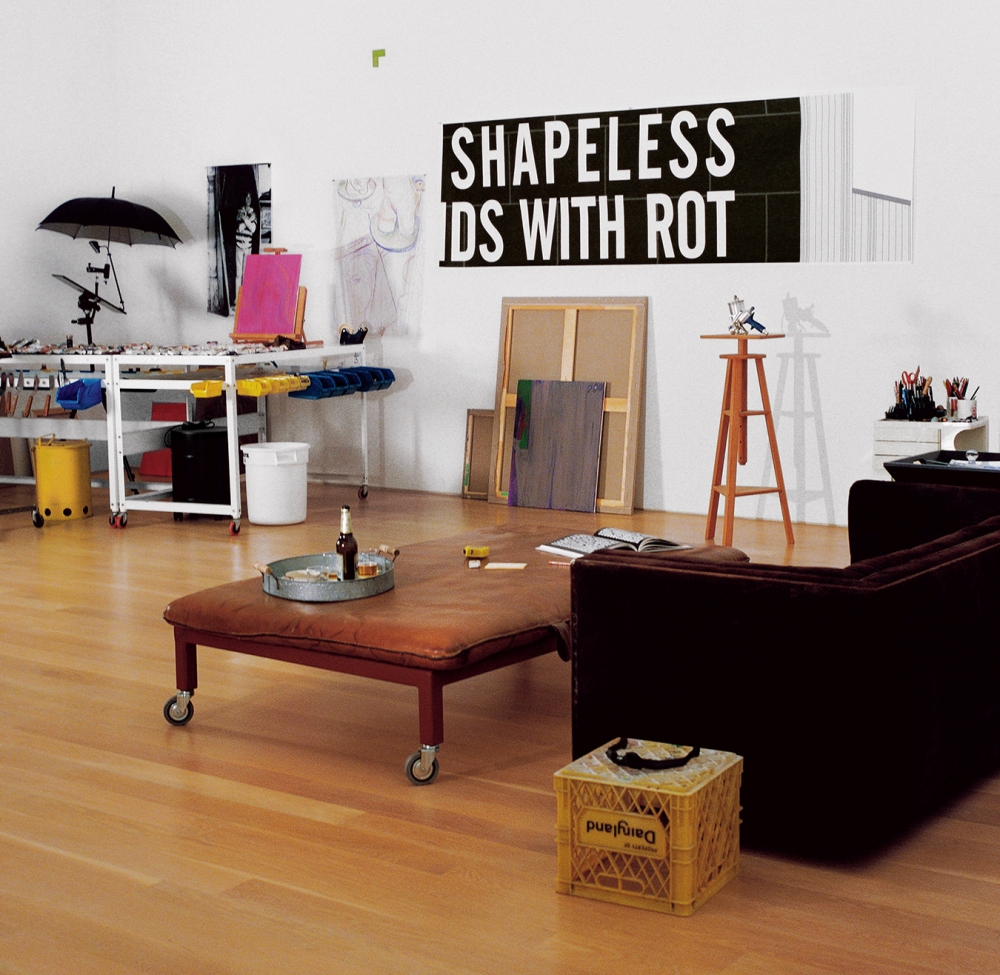

“It’s one thing to generate success and build a studio, and another thing to not be distracted by it,” Shearer says. And it’s here in Vancouver that Shearer will spend most of his time as he prepares to show his work to the world this June. In his studio, paint tubes are meticulously organized. Reference books archive images Shearer has gleaned from the Internet or clipped from books and magazines. All have been arranged by subject in Shearer’s library. (Teen idol Leif Garrett, a prominent figure in Shearer’s work, has three volumes all to his own.) It’s impressive how orderly everything is, but not surprising when you consider that the 40,000 found images Shearer has amassed over the years will eventually be used in one form or another—as a reference for the depiction of a figure in a painting he is working on, or manipulated, grouped and assembled into one of his photo collages or digital prints. Suffice it to say, this is a professional office as much as it is a studio, and Shearer takes it all very seriously.

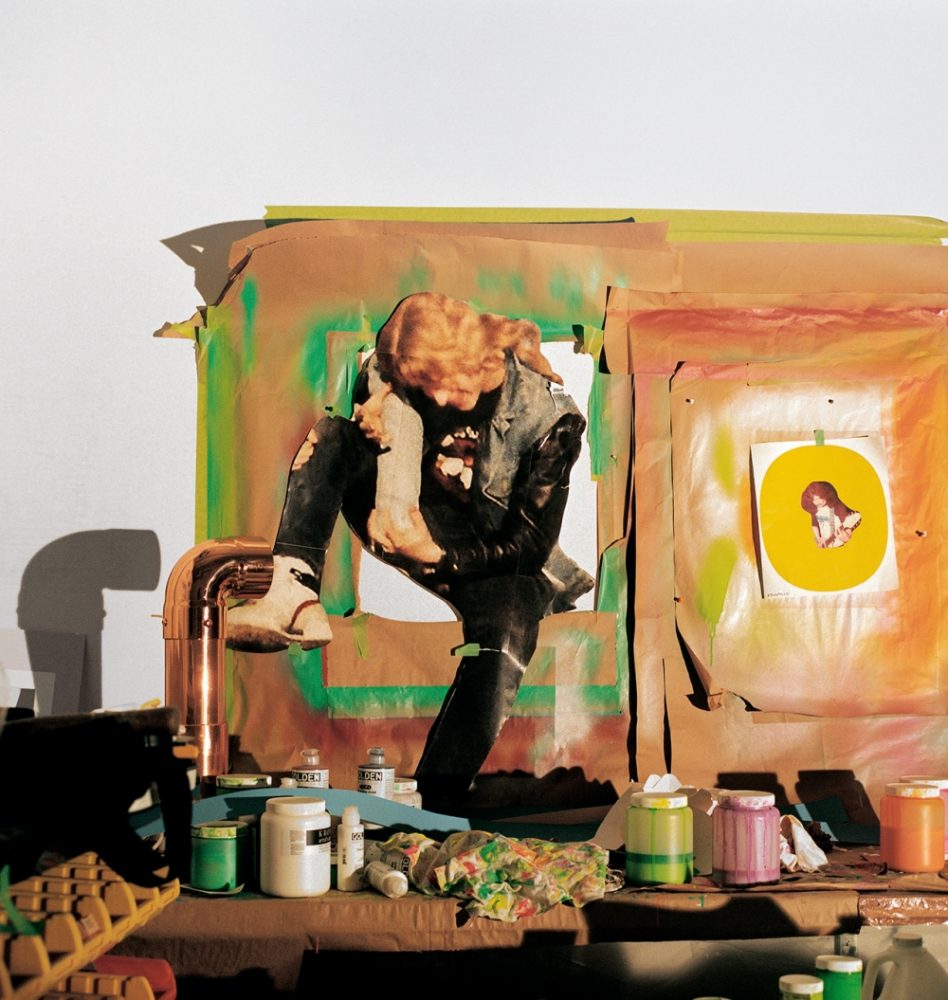

He thinks of himself as a figurative painter first and foremost, but the scope of his work over the years is much broader than that. Earlier pieces like Happy Days are made from thousands of images appropriated from the Internet and collaged together in a mass amalgam of guitar-playing rockers. The sculptural Geometric Mechanotherapy Cell for Harmonic Alignment of Movements and Relations is a jungle gym of hand-polished ABS plastic tubing that emits the low sonic vibrations of bass speakers mounted within. Poems is perhaps Shearer’s most fearless series of works and will play a large part in the Biennale this summer. The charcoal drawings and large-scale public murals of white text on black background contain lines from 127 poems that Shearer has written using a vocabulary from death metal music. When mashed together, the lines create scripts that are so outwardly offensive they are almost crudely entertaining. One wonders how words like “suck my unholy vomit” or “feculent crucifeast” might be received when Shearer constructs a 30-foot-tall by 20-foot-wide free-standing façade to house Poem for Venice outside the entrance of the Canada Pavilion. “I think a lot of people will find the content of the poem an affirmation,” Shearer says. “It appropriates a voice from extreme underground music and expresses sentiments through these kinds of cathartic expulsions. It affirms that everything should be destroyed equally—including the poem itself.”

For those who haven’t seen it, the Canada Pavilion is one of the smallest structures within the Biennale complex. With the British and German pavilions on either side, the Canadia Pavilion will appear to be as tall as its neighbours once Poem for Venice is erected. According to Shearer, it responds to the anxiety that the Canada Pavilion is often perceived as lesser than the others. Shearer will also build a new entrance to the pavilion through a structure that resembles a tool shed—the kind commonly seen in suburban backyards.

Inside, he plans to show a collection of easel paintings, drawings and smaller sculptures. His feeling is that the way the space is set up warrants full use of it. “There is this desire to present one big unified project, but the pavilion is not the place to do that.” The result will be a full-spectrum look at his career so far.

“People look at the paintings and they say, ‘Oh, it’s about rockers, it’s about trashy stuff.’ I don’t feel that way. Sure, they may not be pleasant things—they may even be hostile things—but to me, all of what I do is an empathetic response.”

The romanticized paintings of long-haired teenage boys, the images of death metal bands and the poster poems of heavy metal vernacular may read like an adolescent endeavour to some Biennale visitors, but Shearer explains, “People look at the paintings and they say, ‘Oh, it’s about rockers, it’s about trashy stuff.’ I don’t feel that way. Sure, they may not be pleasant things—they may even be hostile things—but to me, all of what I do is an empathetic response.”

Once called the “bastard offspring of the Photo-conceptualists” by Matthew Higgs in Artforum, Shearer has been considered by some to be a bold choice for the Biennale. When you’re representing not just yourself, but also your country, how much pressure is placed on exhibiting something representative of where you come from? “If you make art about Vancouver, and what Vancouver is about, it’s a bit flat,” Shearer says. “Art is about the person and about the place.” Certainly, Shearer’s artwork is somewhat autobiographical in its response to his adolescent experiences, and he admits, “I like to inject my own kind of personal history and narrative within it.” But, as he elaborates, “If it was all about me, I don’t think it would be that interesting for other people to look at. Collecting all of these pictures can also have an anthropological or sociological feel to it.”

Indeed, his artwork draws on themes from culture at large that people undoubtedly respond to. “For years, my only motivation was enjoyment in doing it. The art-making was a solitary thing I was interested in, and something that made me feel more comfortable being removed,” Shearer says. “The irony is that as the art has progressed, it’s turned out to be a way to connect and communicate with people. I never thought of myself as a traveller, but every place I’ve been to, every person I’ve met … is because of my artwork.” In that sense, Shearer’s art making has been far more than a therapeutic tonic to own his introversion. In his development from afflicted adolescent to internationally acclaimed artist, it has also been the catalyst.