Next to Burrard Arts foundation on East Broadway, there is a nearly unnoticeable side door. Across this threshold is a steep set of stairs, greyish and otherwise forgettable, which wind up to a narrow corridor. The same cramped, industrial atmosphere presumably persists through the hall’s northernmost door. However, the room opens into a spacious studio with windows spanning two walls, proffering a dazzling vista of Vancouver’s downtown centre and Olympic Village.

“It’s an okay place,” says Andy Dixon, the artist to whom the studio belongs, with a mirthful hint of sarcasm. And then, more sincerely: “It’s pretty great.” The room has a comfortable, almost lived-in feel; and though it is certainly capacious, it’s nevertheless difficult to avoid the sprawling, vivid paintings in progress—six altogether—that colour the walls and floor.

Apparently, there is no need to: Dixon plods unceremoniously over the two on the floor, en route to a bottle of red wine, as though they were canvas carpets. “It’s kind of an irreverence to the art object while I’m working,” explains Dixon, now eased into an armchair. “I walk on my paintings, and I use them as their own palettes.” Indeed, off to the side are a couple of spotless, white paint trays that have never been used, and probably never will be.

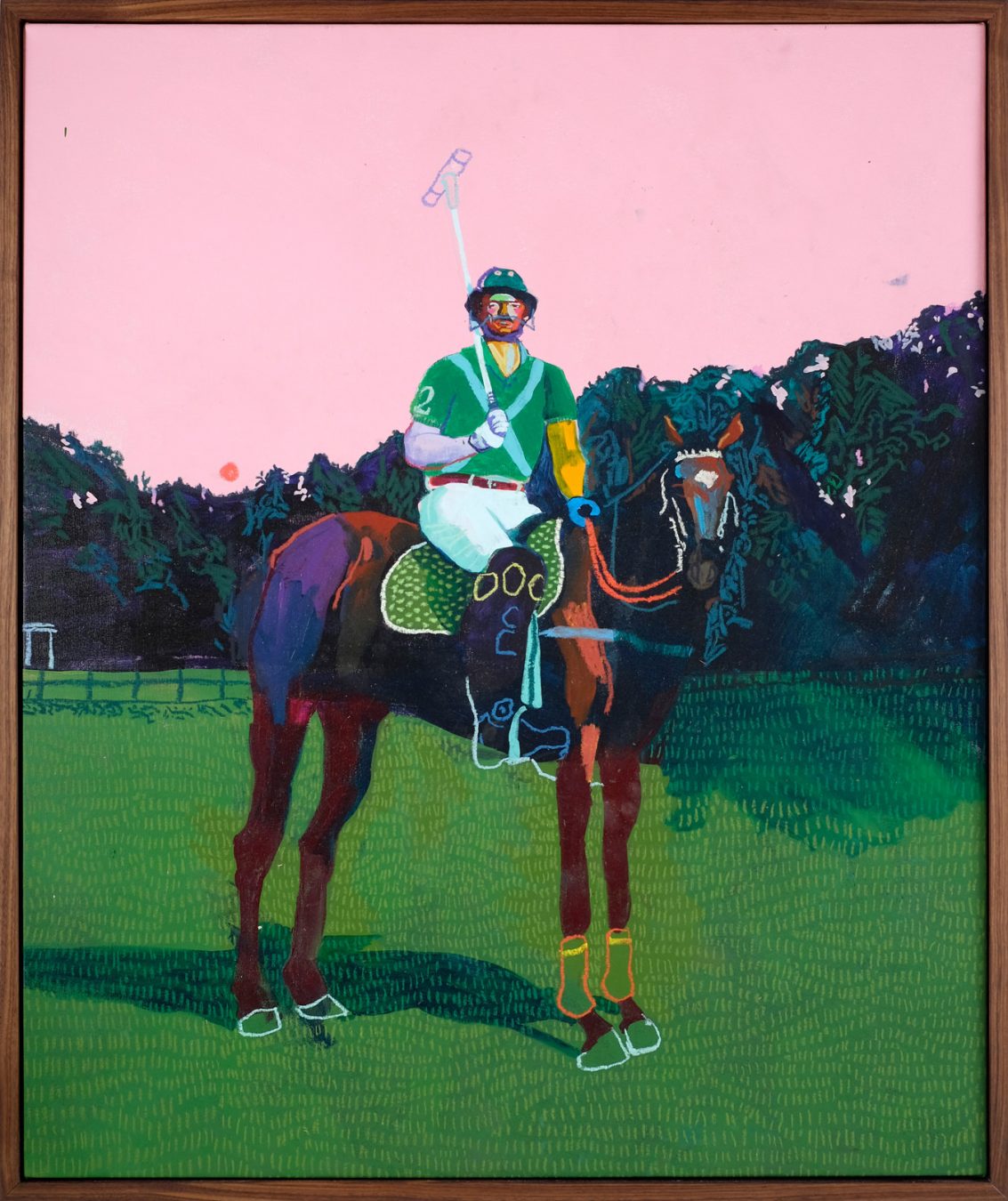

Dixon does not mix paint often; he has collected a handful of complementary colours that recur in nearly all of his works—an unintentional nod to the bright but reproducible effervescence of pop art. While these blocks of colour seem densely tiered, even collaged at times, in truth the paint is applied quite thinly. Adding to the sensation of mixed media are the ornate lines of oil pastel, which guide the shallow swathes of acrylic into meticulously detailed figures.

“There’s nothing ‘good’ about how I apply paint, really. My paintings always look kind of terrible until some detail’s added.”

A large painting, done in the tradition of a Flemish still life, epitomises the technique. The canvas is awash in dark green, with lighter greens, teals, and turquoise blues mottling the foreground; bold pastel lines capture these shades and bind them into diverse forms such as leaves branching from decadent fruit, the rough foliage of a pineapple, and the smooth rind of a watermelon. Dixon’s piece references an actual still life painting, Adriaen van Utrecht’s Banquet Still Life, 1644, and even retains elements from the original—a ham, a lobster, and a lemon with its peel hanging in a delicately-cut spiral—but several items have been swapped out for symbols of exoticism and abundance more readily understood by Dixon’s audience.

“There was a wine bottle in the original painting, but it wasn’t what a wine bottle looks like anymore,” he says. “So I just Google Image-searched ‘wine bottle’ and did a little bit of research on super expensive bottles of wine.” Dixon’s painting, therefore, could be read as a collage of JPEGs arranged in homage to other artworks, or even as appropriation art. But where appropriation art is normally affiliated with neo-Dadaism, Dixon abandons heady academese in favour of beauty: a bold move in a city whose art history is so rooted in the conceptual.

The liberated variegation that typifies Dixon’s work also draws immediate comparisons to the Post-Impressionism of early 20th century France; yet, he traces his technique to a childhood fascination with the art of Jean-Michel Basquiat, wherein opaque oilstick illustration overlays impulsive applications of paint. Between all these styles and movements, Dixon’s practice seems to run a broad art-historical gamut; nevertheless, with no formal art education, he stumbles upon these allusions by happy accident, assembling a knowledge of art history on the fly as critics read references into his work. “There’s nothing ‘good’ about how I apply paint, really,” Dixon muses modestly. “My paintings always look kind of terrible until some detail’s added.”

He has only considered himself a painter for the last few years, and was involved in punk and experimental electronic music scenes for nearly two decades prior.

A philosophy is embedded in Dixon’s self-deprecation. The shift from mundaneness into beauty, from an attitude of irreverence to one of awe, is a persistent theme underscoring his work. It can be perceived as one moves from the nondescript stairwell into the vibrant, scenic studio; it resides in every painting, whose lavish hues and luxurious imagery—the current selection features a gala ball, a dinner party, a reclining nude, a horse-mounted polo player, and the still life—belie the artist’s casual indifference to the subject matter. And fascinatingly, the paradox existed in Dixon’s music career.

He has only considered himself a painter for the last few years, and was involved in punk and experimental electronic music scenes for nearly two decades prior. “I was sampling Top 40 music and making something new out of it,” Dixon recalls. “There would be a certain irreverence to that subject matter, but I also found myself trying to figure out the best moments in each song.” Just as poking fun at pop music prompted a desire to produce good tracks, Dixon’s flippancy towards his paintings manifests sumptuous, even provocative works.

Dixon, it seems, is an irrepressible humourist. Venturing further into his past, he remembers as a child trying to draw comics in the same vein as The Far Side to amuse his parents. Today, irony and jokes are still integral to his pictures. In a cheekily self-reflexive gesture, his still life painting—itself an emblem of status—materialises in the background of his highfaluting dinner party scene. Both pieces were exhibited at Art Paris in March 2015.

Needless to say, as gallery-goers contemplate Dixon’s “obvious Fauvist inflections” or “tributes to Rousseau”, this shamelessly outsider artist may just enjoy a well-earned, though appreciative, chuckle.