“There’s a lot of people,” Robert Creeley says, laughing with either nerves or disbelief. He’s shepherding a child up to the front of the room: “Go ahead. This is how you do it.” The child, now close to the microphone, confidently declares, “This is a bus poem,” before reciting a few nonsensical lines about a “bus garage.” The audience claps and laughs. Creeley returns to the microphone. “Let’s see if I can beat that.”

A storm is beating against the modernist concrete of the Buchanan Building at the University of British Columbia, and the audience listens in rapt silence as Creeley, one of the most distinctive and influential American poets of his time, begins. He reads a couple of poems with a quavering voice before attempting “The Ball Game”:

The one damn time (7th inning)

standing up to get a hot dog someone spills mustard all over me.

the conception is…

He falters, mumbling, “Let me try that again,” before beginning again. By the time he builds to his defining poem, “I Know a Man,” he’s regained his confidence. He pauses at the end of each of the 12 lines—his characteristic style—and forcefully enunciates the oft-cited conclusion:

drive, he sd,

for christ’s sake,

look out where yr going

He pauses for a cigarette and asks the audience for a match. He reads a few more poems and says, “I’m relaxing now.”

Fourteen minutes into the reading, the recording stops abruptly. Larry Goodell, a poet and publisher from New Mexico, who was in the audience that evening, described the episode in a stirring letter to a friend a few weeks later: “Thunder/rain and the lights went out. Warren brought in a couple candles and Bob read with all of us sitting around, by candlelight. It was so curiously fitting.”

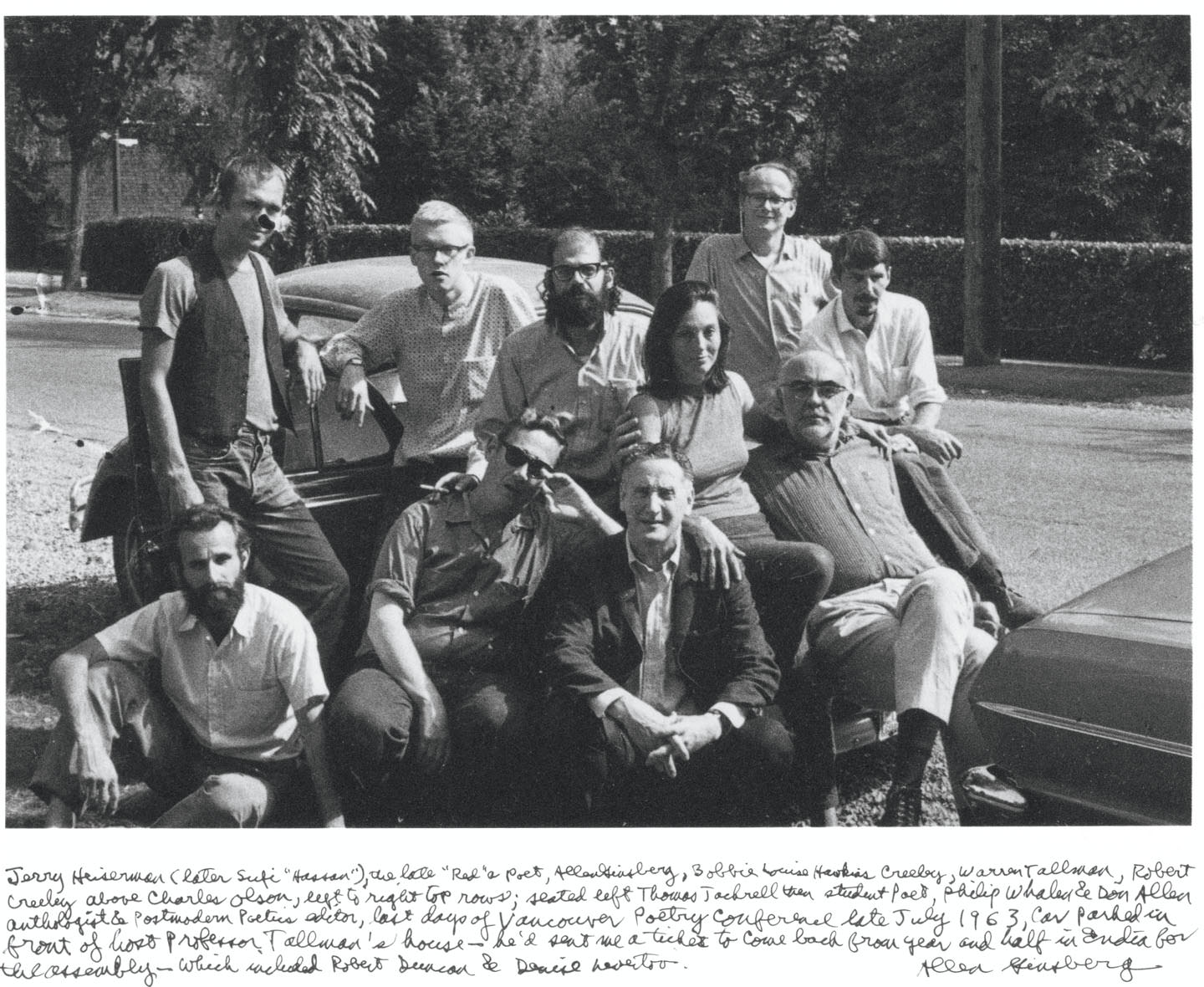

The Vancouver Poetry Conference in the summer of 1963—though not a conference in any traditional sense of the word—which brought a gang of poetic luminaries, including Allen Ginsberg, Robert Creeley, and Charles Olson together for three weeks of readings, lectures, and celebration, has since been dubbed a poetry Woodstock. “There were impromptu readings going on all over the city, and huge parties at people’s houses,” recalls George Bowering, the first Canadian parliamentary poet laureate.

The thriving Vancouver literary scene of the early 1960s was, in large part, the work of UBC professor Warren Tallman—he who had brought candles when the lights went out. The American-born Tallman studied at Berkeley in the late 1940s, where he met his wife, Ellen, and became acquainted with a number of writers active in the San Francisco Renaissance. Both Warren and Ellen accepted positions in the English department at UBC in 1956 and settled in a home on West 37th Avenue in Kerrisdale.

Though a bespectacled academic in appearance, Tallman was far from a conventional professor. “A lot of people didn’t have a clue what he was about because he never did anything the way anyone else did,” Bowering remembers. He soon developed a following among aspiring writers on campus who flocked to his Studies in Poetry course.

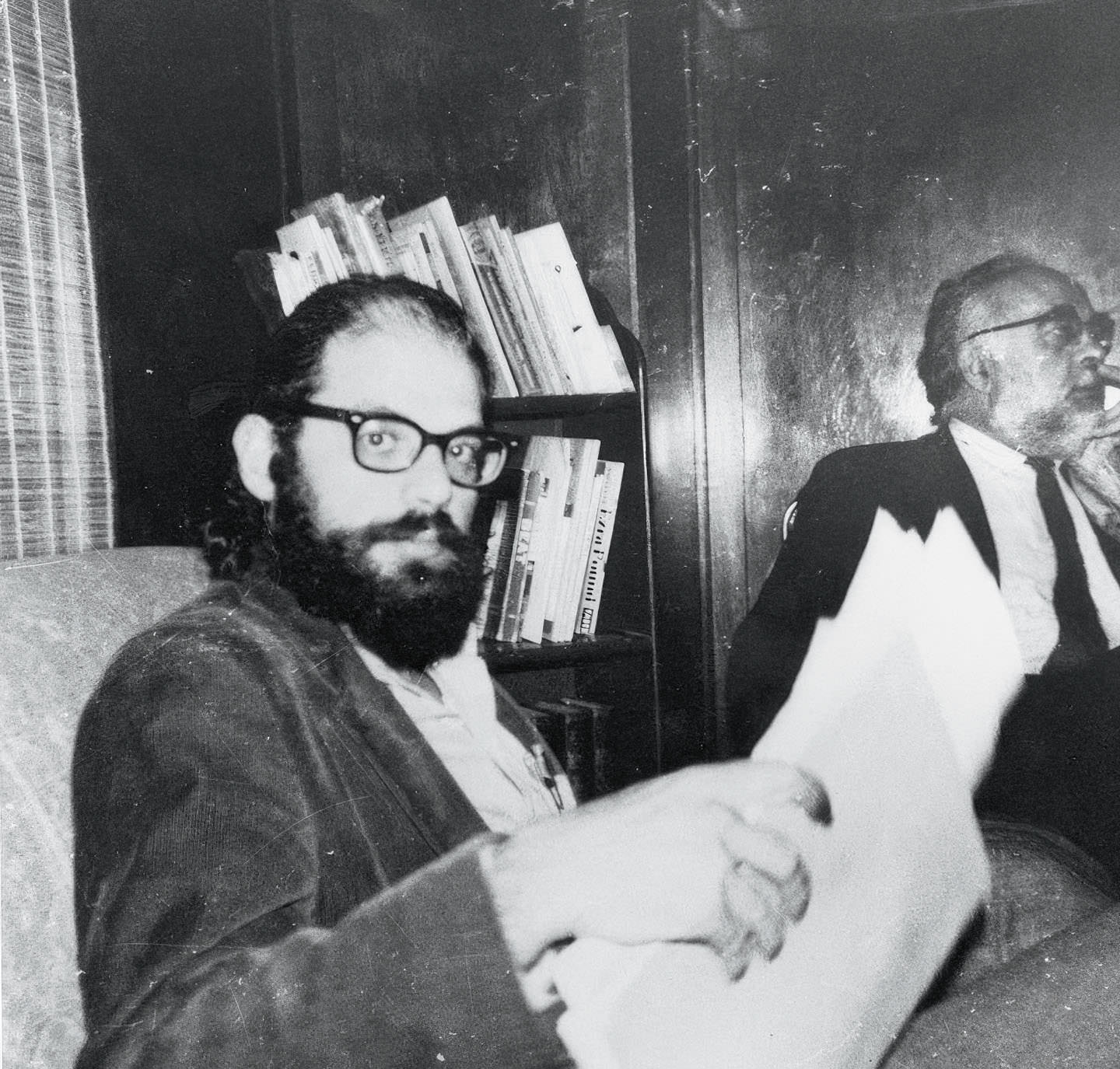

Allen Ginsberg with Charles Olson at Warren Tallman’s house, summer 1963. Photo by Karen Tallman. Courtesy of University of Connecticut, Charles Olson Research Collection.

The Tallmans made their home available for rowdy literary readings and lectures, and frequently hosted writers from out of town. In 1961, a group of UBC students, including Bowering, Maria Hindmarch (then going by her first name, Gladys), and the soon-to-be-married Pauline Butling and Fred Wah, seized on this energy and founded an irreverent literary journal called Tish, drawing inspiration from the radical open form of The New American Poetry 1945-1960 anthology—then hot off the presses. “It was the ’60s,” Bowering says, “and poetry was something that seriously happened.”

To expose the Tish poets to the wider literary world, Tallman arranged a year-long teaching position in 1962 for Creeley, a friend of Ellen’s from back in California, with the intention of collaboratively planning an event for the following summer. Writing to Creeley in April 1962, Tallman envisioned “a big open house with everybody available to everybody and it all swinging.”

After a period of deliberation—and some squabbling—six poets were selected: Creeley, Charles Olson, Allen Ginsberg, Denise Levertov, Robert Duncan, and Margaret Avison, the lone Canadian, included “as a concession to national whatever pride,” according to Tallman. It would be hard to overstate the poetry star power of this lineup. “We treated them like sensei,” Bowering says.

Vancouver’s “poetry Woodstock” sparked impromptu readings all over the city. Photo by Ron Bayes. Courtesy of Larry Goodell

Festivities commenced on July 24 with a conversation between Creeley and Allen Ginsberg, the shaggy hero of the counterculture who had successfully defended his landmark poem, “Howl,” against charges of obscenity back in 1957. The two poets started with the basics of writing instruments. “I get very nervous about using pens, because they run out of ink,” Creeley admitted. “I use a notebook, otherwise all the papers would get lost and it would be too much to carry around as I travel,” Ginsberg offered.

Fred Wah, another future Canadian poet laureate, was in the lecture hall that day armed with a reel-to-reel recorder. It was not always easy work. At one point, Wah remembers, “the tape recorder had broken, and I had to sit there recording someone’s reading with my finger on the takeup reel.” Fortunately, the recordings were preserved and later digitized by the University of Pennsylvania.

On August 14, Charles Olson read for an hour and a half, working his way through a bottle of Cutty Sark whisky, until the janitors closed the building down.

From the very first session, it was clear the conference would not be a standard academic affair. The poets discussed the jazz they listened to and were candid about the drugs they consumed. They encouraged participation from the audience and discouraged note taking. “It was like a group exchange, and the conversation went on all day and all night,” recalls Butling, a professor and writer who assisted Tallman. While the overall atmosphere was “definitely male-dominated,” she also notes that “there were a lot of really strong women in there who didn’t hesitate to speak up and claim their space.”

One of these women was Hindmarch. On the morning the conference began, she was working on a freight boat in the Vancouver Harbour. While she was given time off to attend the conference, she planned to attend regardless: “When I saw that the conference was coming,” she says, “I thought, damn it, I’ll quit work for that.” She picked up her paycheque at the docks around noon and received a ride from her sister up to campus, where Creeley and Ginsberg’s discussion was already underway. She claimed the last seat in the house and sat down to realize the man sitting beside her was the famed painter and poet Roy Kiyooka.

Hindmarch, like many of the conference attendees, was especially excited to see Charles Olson. At a bearish six foot seven, Olson’s stature matched the magnitude of his literary work: in 1963, he was in the midst of writing his sweeping series The Maximus Poems, and his earlier essays like “Projective Verse” had theorized a radically more open and embodied approach to poetry. On August 14, Olson read for an hour and a half, working his way through a bottle of Cutty Sark whisky, until the janitors closed the building down. He continued with another two-and-a-half-hour reading two days layer.

Bowering remembers that he and his peers repeatedly implored Olson to recite his poem “Maximus to Gloucester, Letter 27 [withheld],” which reflects on the summers Olson spent as a child in Gloucester, Massachusetts. He intones with Shakespearian seriousness near the beginning of his second reading:

I come back to the geography of it,

the land falling off to the left

where my father shot his scabby golf

and the rest of us played baseball

Despite the heavy schedule of lectures and readings, there was still plenty of time for extracurriculars—the bars, the beach, and even the zoo. In an essay written shortly after the conference, Tallman recalls that Ginsberg “went the most places, eastside, westside and all around Vancouver. He sat, crouched cross-legged or stretched out on the most lawns, couches, chairs or floors in the most houses, apartments and pads, even in a kayak.”

Goodell’s letter elaborates: “Allen paddling in a kayak out from shore, Vancouver Bay, at dawn, his jacket ends dragging in the water, getting out pretty far shouting HOW DO YOU TURN THIS DAMN THING? And we shouting back instructions till he finally got back.”

It was, Creeley would later say, “one of the wildest things ever to happen, to me at least.” For the first generation of Tish poets, it was a grand finale: most of the founding editors had finished their schooling and soon left the city for jobs or graduate programs. In the years following, an impressive portion would become respected writers and teachers themselves. A follow-up conference took place in Berkeley in 1965, but the freewheeling energy of those three weeks could never be replicated. “It was just one of those historical moments, where various things converged,” Butling says with a smile.

At some point, every conversation about the conference drifts toward a party hosted at Butling and Wah’s apartment. “We had about 80 people in our small apartment,” Butling says, “and the energy—not just for people partying, but the conversations and the arguments—was just so alive.” Sixty years later, the most moving encapsulation of that legendary party can be found in Hindmarch’s poem “Kitsilano (1963-69)”:

that crazy night at the Wahs’ place

if that wasn’t a party of this kind

everybody landing on that bed

everybody kissing everybody

we had to go outside to pee

because the lineup for the can so long

somehow to do with that small space

that it was so tight that everybody had to rub every

body simply to go anywhere

It was gorgeous

Read more from our Summer 2024 issue.