There probably isn’t a major artist who doesn’t know this story: you’re, at best, appreciated during the struggle of life, and then loved and hailed a genius after the cold embrace of death.

And then there are the extreme cases, where not just some but all the praise comes when the author isn’t there to hear it: the vast majority of Emily Dickinson’s poems, E.M. Forster’s Maurice, John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces. The writer loved by publishers is not always the writer whose work will be loved decades after the fact.

When Steven Price was a student in the University of Victoria’s writing program, the literary world was shifting—the barriers of national literatures could seem, from an optimistic vantage point, to be forming a Pangaea of shared influences and inspirations. Atwood and Ondaatje were proving Canadian writers didn’t have to only be provincial talents, novels in translation were easier to get one’s hands on, and a new generation of Canadian writers, the ones canonized, if not to the level of Atwood, were taking posts at universities.

Jack Hodgins, who had three works published in the second wave of the New Canadian Library series, was teaching at UVic at the time, and is part of how Price encountered The Leopard, the single posthumously-published novel by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, and a book that Price couldn’t shake for two decades.

“It was a novel that was being passed around among students, partly because it was recommended by [Hodgins],” Price tells me by phone from a B.C. ferry. “It was such a strange book: the way that it played with time, and the way it was structured and built, was unlike anything I’d seen before in fiction … I didn’t really know what to do with all of that when I was in my early 20s.”

Tomasi’s novel, like many masterpiece-level classics, is concerned with social change. When it was eventually published, it met with public controversy in Sicily, where it is set; became a best-seller; and was adapted into a film by Luchino Visconti, itself a lauded work that has impressed no less than Martin Scorsese (if early notices are to be believed, his latest film takes a page or two from Tomasi’s narrative of what time does to empires).

Publicity still from Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard (1963).

But this is what time in retrospect does: it makes it all look easy. The publishers who rejected The Leopard were mistaken, and now we know the book was great all along. Price wanted to immerse himself in the other side of things, when nothing was certain.

He’s written a historical novel, Lampedusa, now nominated for the Giller Prize, that considers not the book’s reputation, but the actual lived experience of all the life that went into it. If The Leopard, as Scorsese puts it, is “a meditation on eternity,” then Lampedusa reflects on and sinks into that meditation. It’s a work searching for the scattered beauty that Tomasi distilled into his art, surrounded, as he was, by a life where all the outer markers of success (his property, his social standing, his health and progeny) were compromised or lost.

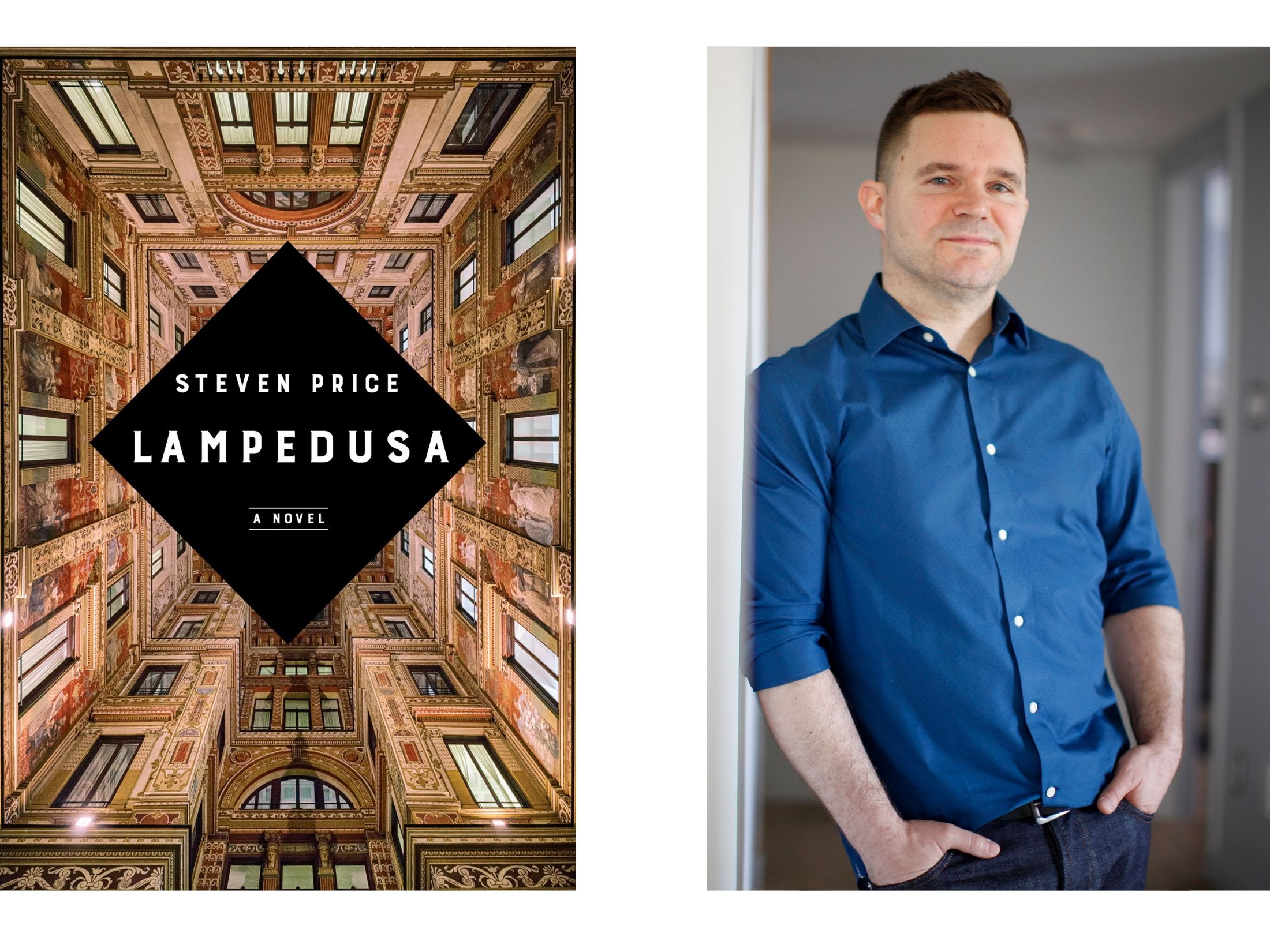

Photo courtesy of Chad Hipolito.

“I felt perplexed and moved by how much this novel, that was so far removed from my own existence—how much it could matter to me,” Price says. “If it had been a book that I could simply say, well, that matters to me because my whole family’s from Sicily, I’m not sure that I would have felt the same mysterious source that I wanted to get close to, to try to understand something there.”

Price draws from David Gilmour’s The Last Leopard as a biographical source, but what he really does for the reader is let us in on the lonely, often mythologized germination of a life’s work. Tomasi is surrounded by his wife, and a young couple, and a couple of relatives—they supply the warmth and tension of Price’s novel. But the real drama here is the delayed, winding trail of becoming, its disappointments and embraces alike.

“I like the word correspondence,” Price says. “An unanswered correspondence, of course, a one-sided correspondence with Tomasi, the author and the person. And, of course, his book. I like to think that there is hopefully a resemblance in the portrait, but at the end of the day this is my version of Tomasi.”

Steven Price will be at this week’s Vancouver Writers Fest to talk about Lampedusa at three different events, beginning with the festival’s opening night gathering of Giller Prize nominees.

Dig further into the Arts.