Since its humble origins in a West Vancouver garage near Bertram Charles Binning’s home half a century ago, the Dundarave Print Workshop has seen hundreds of artists create prints on its traditional, hand-operated presses. As the oldest continuous printmaking studio in the province, the workshop is now an indelible piece of the renowned B.C. artist’s cultural legacy.

Binning was the power behind making the print workshop happen, co-founder and artist Wayne Eastcott recalls in an email interview from Japan, where he now lives. “It was the beginning of the printmaking explosion that had its germination in the late ’60s. It was an exciting time.”

Bert, or B.C. as he was later known, was born in Medicine Hat, Alberta, in 1909. Four years later, he moved to Vancouver with his parents and younger sister, Margaret.

Binning began drawing as an adolescent when an illness left him bedridden. Though he came from a line of architects, he chose to pursue the visual arts following high school, enrolling in the Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Arts. He later returned to the art school as an instructor in 1934, and would continue to teach for the rest of his working life.

Two years after embarking on his professional path, he would marry his wife, Jessie Isabel Wylle. The couple met through friends, their wedding held at the bride’s home in Gleneagles, West Vancouver. Bert was 27, and Jessie, an only child, four years his senior. According to prominent B.C. architect and friend Arthur Erickson, the union was a case of opposites attracting. Bert was considerably taller, with an expansive sense of humour, and Jessie exemplified grace and refinement. Together they would nourish Vancouver’s art world in a multitude of ways.

In 1941 the couple settled into a pioneering West Coast modern post-and-beam house on Mathers Crescent in West Vancouver, after Binning convinced skeptical mortgage lenders its “radical” flat roof was structurally sound.

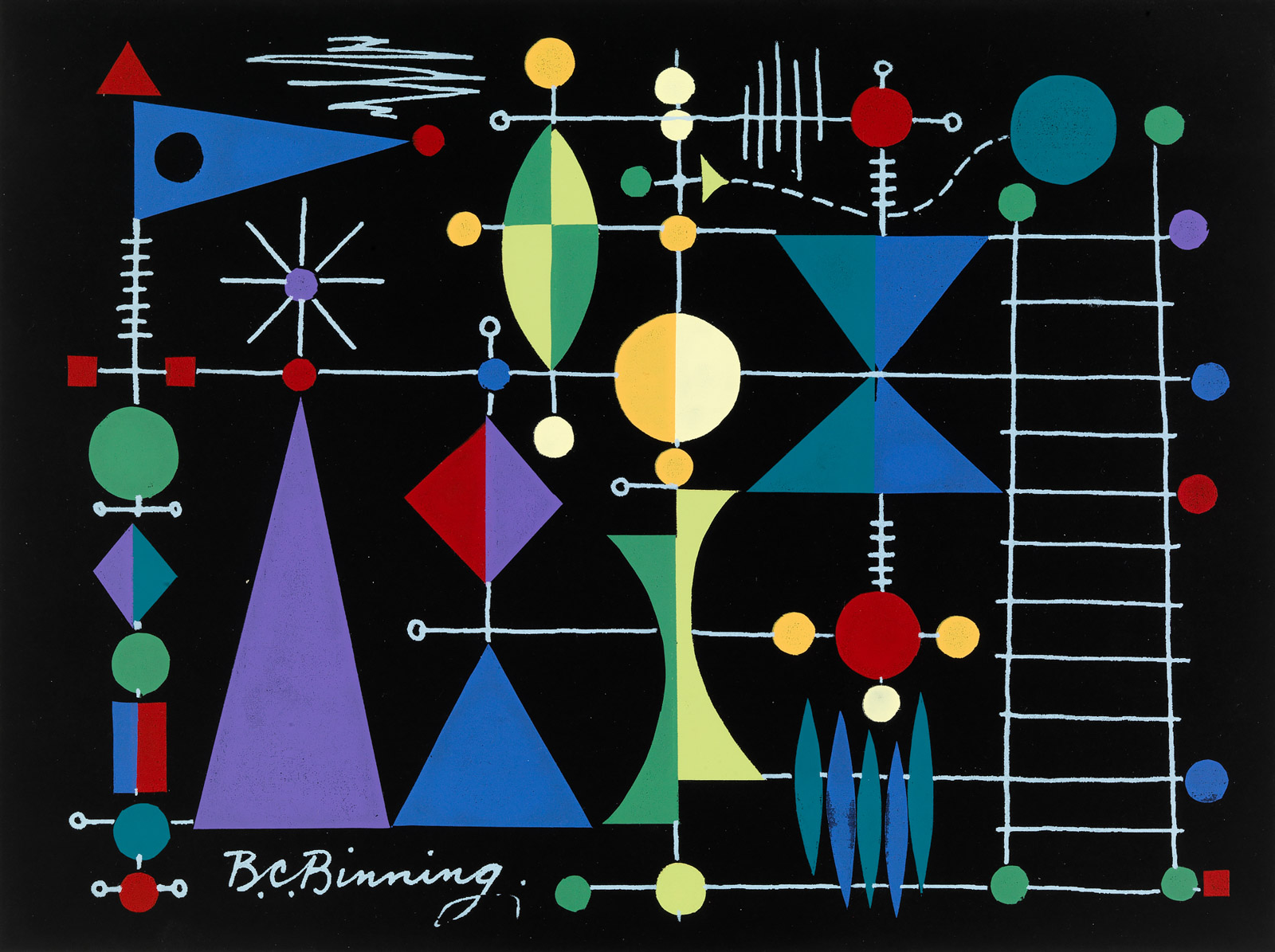

B.C. Binning, Autumn Vine, 1970, screenprint on paper, 47.7 x 62.6 cm, Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, Gift of Mrs. Jessie Binning.

Binning designed and built the residence with local fir and cedar, the stone for the fireplace from the nearby Cypress Creek. Saturday night parties started at 8 p.m. and wrapped up with coffee at 11, with lots of music and conversation among an array of singers, jazz musicians, artists, and dancers.

When he wasn’t working in his art studio at home, Binning commuted to his teaching position in Vancouver across the Lions Gate Bridge. He began teaching art in the architecture department at the University of British Columbia in 1949 and six years later established and headed the school’s fine arts department. Known for his warmth and humour, Binning encouraged generations of art and architecture students—including Arthur Erickson—to think and see in new ways.

Binning and his wife travelled extensively, especially drawn to the culture of Japan. The couple enjoyed sailing the local waters in a 20-foot boat Binning partially built. He frequently depicted marine activity in his art, once commenting: “there’s always something curious happening—a small boy fishing, a man furling his sails, somebody rowing from one side of the bay to another.”

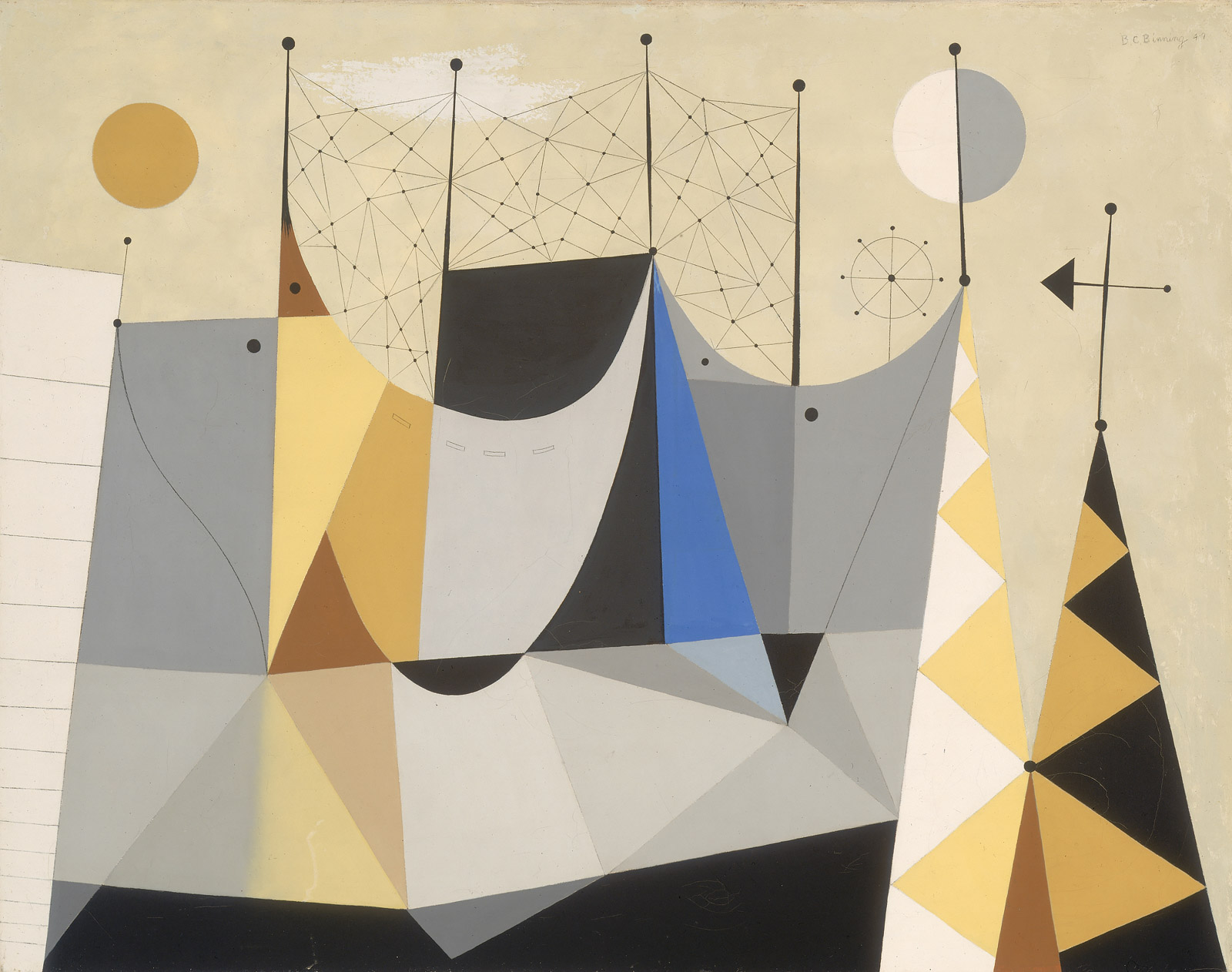

Many have described his art as lyrical; he relished the simple line and had a keen interest in draughtsmanship and design. Binning aimed to capture what he called the “lyric idea” and, as he evolved, he became increasingly interested in symbolism, not realism, in his images. A portfolio of pen-and-ink drawings, acrylic and oil paintings, and mosaic murals on public buildings accumulated over the decades.

Binning’s prints—though lesser known—included woodcuts, linocuts, and etchings, some now held by the Vancouver Art Gallery, along with a series of silkscreens he executed in 1970, depicting the vine leaves in his home garden. By the time he was recognized as an Officer of the Order of Canada in 1971, his art was showcased internationally and displayed in galleries across the country.

Looking back on his oeuvre, Binning once said art “plays between the two sides of me… a certain joy and fun—perhaps even wit—but this seems to vacillate between another extreme of plain coolness, which I call a classic sense.”

Binning first floated the idea of a local print workshop to Eastcott after stepping down as UBC department head in 1968. Back then, the North Shore was still a relatively affordable area for artists to live and work, with a vibrant cluster of galleries and coffee houses along Marine Drive.

“Bert and Jessie were friends from around 1969,” Eastcott recalls of his relationship with the couple. “He was in poor health and was not then actively painting, having finished the large Optional Module works. However, we spent a lot of time talking and laughing.”

“Bert and I had our own studios,” Eastcott notes, “and didn’t really need a print shop, but we were very interested in doing what we could to encourage, support, and advance the West Coast art community. So we were mostly doing the paperwork and whatever else we could to make it happen. I say ‘we,’ but, as you can imagine, it was Bert who was really the power that made it happen.”

B.C. Binning, Fair Weaather Signals, 1949, oil, ink, pencil on canvas. Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, Bequest of C. S. Band.

Binning invited Eastcott to his house on April 25, 1971, along with young printmakers Dan MacDougal, June Hodgson, and Martha Reed. MacDougal, who lived in the nearby Dundarave neighbourhood, had offered his garage as a studio. A Charles Brand etching press was moved in, taking up half the space. Counter surfaces quickly accumulated an acid bath, ink jars, and other printing supplies. Now five artists were gathered in Binning’s living room with its floor-to-ceiling glass wall facing the garden and sloped woods, to sign a constitution establishing Dundarave Print Workshop.

A membership drive ensued. Arnold Shives, a Vancouver artist, remembers Eastcott offered to teach him printmaking if he joined. Shives agreed, the experience resulting in a significant change in his artistic direction.

“The first thing to do was strike a match and light the oil heater,” Shives recalls in an interview. “There was no running water so I would fill buckets from a tap outside the main house.”

Eastcott taught many more students for several years. “That’s where Mary Blaze came in,” he says, “along with others such as Bonnie Jordan, Margaret Witschze, and Casey Brown. They became the foundation that brought Dundarave Print Workshop, under the leadership of Leonard Brett, into what it is today.”

When Binning died at age 67 after a lengthy illness in 1976, he left his wife, sister, a niece, and a nephew. Eastcott kept in close contact with Jessie. “The influence of both Bert and Jessie was important to me far beyond what we did around Dundarave Print Workshop,” he says.

A memorial scholarship was set up in Binning’s name at the Dundarave Print Workshop (which relocated to Granville Island in 1979) and Jessie became an honorary member, along with B.C. artists Alistair Bell and Gordon Smith. Jessie remained in the house that “moves with the sun,” as she once said (it was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1997), until her death in 2007 at age 101.

Today Dundarave Print Workshop remains small and focused, its artists still dedicated to traditional intaglio and relief printmaking. Its constitution, drawn up by Bert Binning long ago, promised “a professional atmosphere for the purpose of carrying on printmaking.” Binning would be pleased to know artists have stayed true to this mandate—and his “lyric idea”—for an enduring 50 years.

Read more local Art stories.