For Dana Claxton, Indigenous art can be a powerful means to foster new understanding. The acclaimed multidisciplinary and multi-award-winning artist (including most recently the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts), is also head of the University of British Columbia’s department of Art History, Visual Art & Theory. In 2018, she mounted a major survey of her 30-year-career at the Vancouver Art Gallery. In this story from our archives, we look back at some of the most striking pieces from that exhibition, in conversation with Claxton.

Dana Claxton knew she wanted to be a filmmaker from the age of five. The Hunkpapa Lakota (Sioux) Moose Jaw-raised artist recalls her fascination with the black-and-white television of the early 1960s, and her inspiration when she looked up into the expansive Saskatchewan sky. “It’s the biggest screen in the world,” says Claxton over tea and soup at Vancouver’s La Petite Cuillère. “There’s a saying: ‘Everything you need to know is in the sky.’”

Claxton descends from the Hunkpapa Lakota band of Sitting Bull, who moved north to Saskatchewan in the late 1800s. She first became aware of her cultural identity in school, but it took an incident in a Williams Lake, B.C. restaurant many years later to entrench her self-identity. An Indigenous woman had chased her into a bathroom stall, where Claxton screamed, “Why do you want to hurt me? I’m like you. I’m your sister. I’m ‘Indian,’ too.” The terrifying experience was a “beautiful moment” for Claxton to self-claim, to declare, “This is who I am”—a powerful statement she carries throughout her practice. “There’s a real privilege in making art,” she says. “And there’s also a type of liberation in making art.”

Today, Vancouver-based Claxton is a celebrated multidisciplinary artist, and an established professor at the University of British Columbia, where she chairs the visual arts program. Her three decades of works in film, video, photography, and performance have been widely exhibited, including at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. Three years ago, the Vancouver Art Gallery exhibited her comprehensive works in “Dana Claxton: Fringing the Cube,” a collection that projected Claxton’s important voice in reclaiming the Indigenous narrative, showcasing her explorations of stereotypes, beauty, and visibility.

Claxton challenges Indigenous representation by “collapsing the aesthetics.” Her early film The Red Paper (1996) tells a story of the European colonization of the Americas, but portrays the power dynamics of the experience inside-out: Indigenous actors play starring roles and speak Elizabethan English in European dress. And in the photographic series The Mustang Suite (2008), Claxton presents members of a family with different versions of the “mustang” in odd combinations of traditional and contemporary contexts. The father, in a suit with a painted face, stands next to his Ford Mustang in one photograph, while his twin girls wear mukluks and ride Mustang bicycles in another.

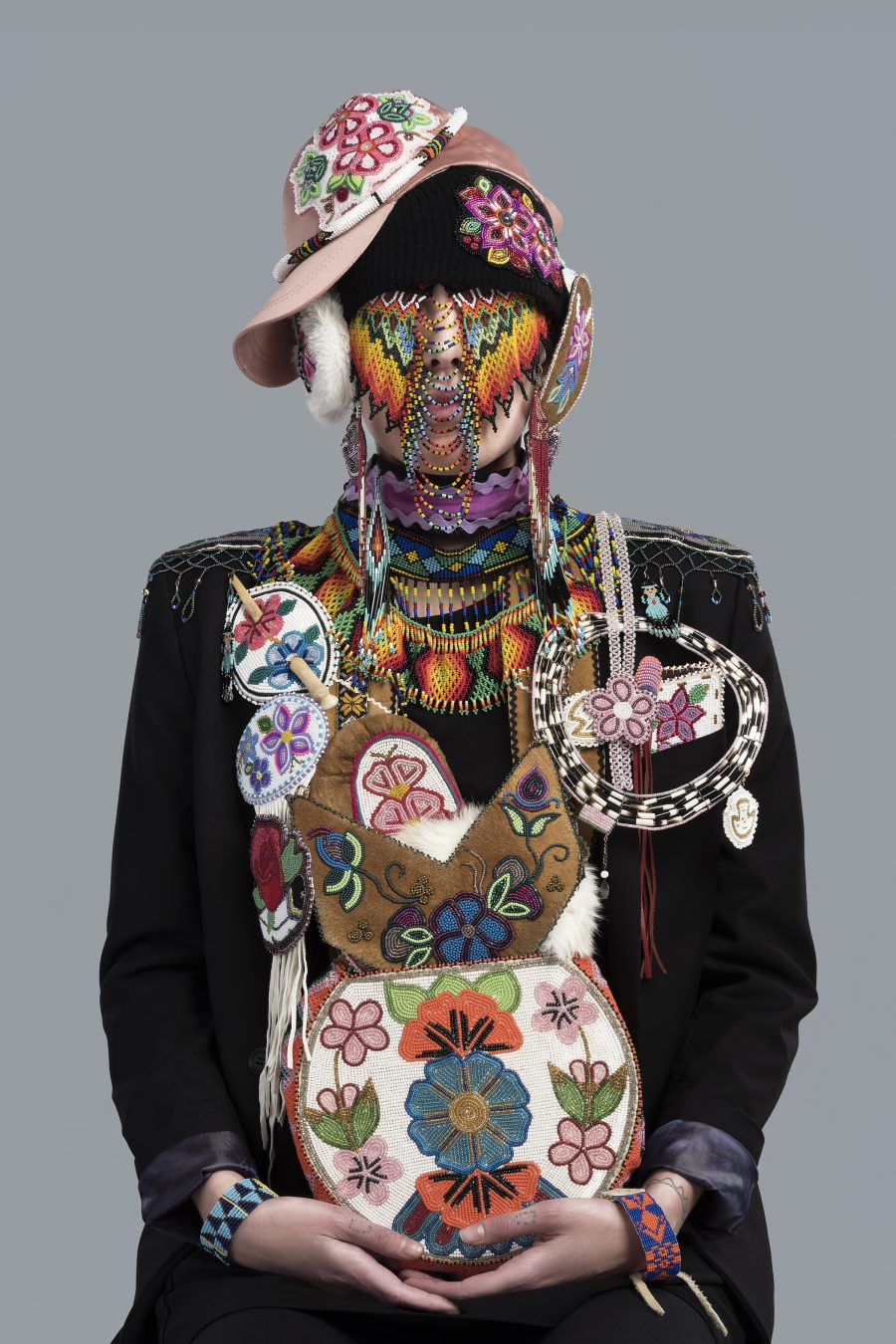

Themes of beauty and objectification pervade in Claxton’s female-centric photographs. Onto the Red Road (2010) is a series of five life-size prints of a woman in variations of a red dress, representing the criminalization of regalia, and both the sexuality and spirituality of Indigenous women. Headdress (2015), meanwhile, captures the power of everyday objects. An image of a beaded headdress obstructs the face of an Indigenous woman inside an illuminated lightbox, stressing how identity is defined and projected.

Claxton’s Vancouver exhibit also identified the (in)visibility of Indigenous peoples. Her mixed-media installation, Buffalo Bone China (1997), delves into the extermination of the buffalo and the transformation of its bones into British bone china. Paired with a stirring soundtrack, it exposes the dire historical consequences for the Indigenous people of the Great Plains.

“When I think about my relatives starving, while people are eating with fine bone china, I’m like, ‘Who does that? Who would exterminate such a significant, beautiful being?’” she says. “It’s a haunting work. It was a haunting experience. And I personally think it continues to haunt the landscape of Regina.”

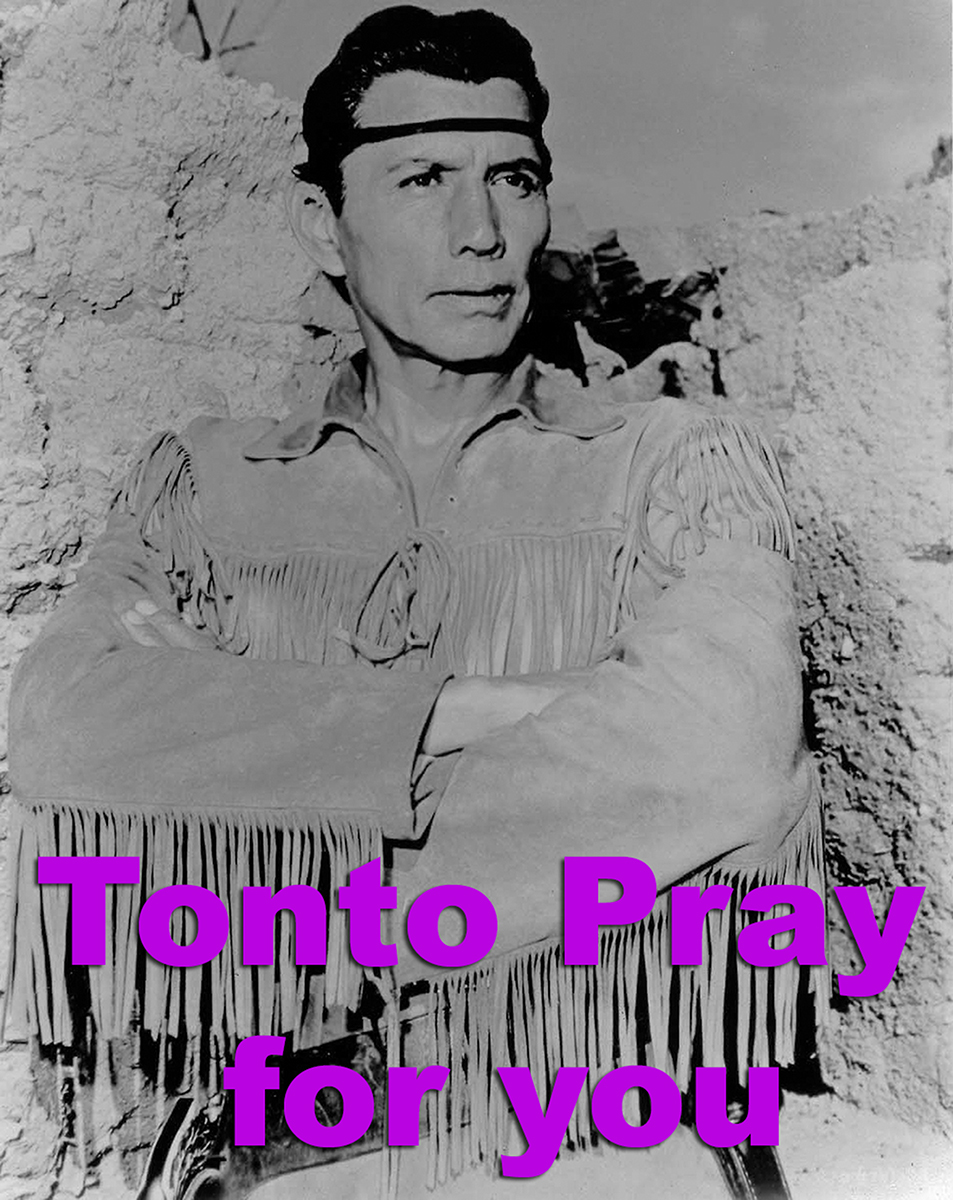

Then there is Indian Candy (2013), which uses an explosion of colour, combined with influences from pop art and Hollywood glamour, to showcase “sweet” stereotyped images of the Wild West (Tonto from the 1950s TV series Lone Ranger among them). The prints illustrate the longstanding portrayal of Indigenous people in contemporary society.

Claxton is the recipient of numerous awards, including a prestigious fellowship from the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art—however, she credits her working relationships with her community as most rewarding. “If I’m going to go up in this business, I want to bring as many people with me,” she says, citing a shared philosophy. Because for Claxton, the sky has no limit.

This story from our archives was first published Oct 31, 2018, and updated May 3, 2021. Read more Arts stories.