Evan Lee likes to tell the story of the high-school trip in the early ’90s to the Vancouver Art Gallery where he first encountered Jeff Wall’s 1989 photograph Outburst. The staged, large-scale image shows a furious male boss, his body positioned like an action figure, railing at a female worker in a garment factory. “It was like seeing my life reflected in an art gallery,” he says in a coffee shop not far from his house in Riley Park, which he shares with his wife and their teenager.

Lee’s mother spent her working life as a seamstress at a denim factory in East Vancouver. “My dad and I would pick her up at the end of the shift,” he says. “He’d keep the car double-parked and I’d run upstairs and go fetch her.”

Today, a successful white artist like Wall using a Hollywood-production budget to recreate a scene from the lives of racialized working-class people might leave a young artist outraged. Instead, Lee describes himself as “blown away.” (Wall later contributed the foreword to Lee’s Captures exhibition catalogue, where he wrote: “Lee’s reticent imagery is connected with a tradition of poetic evocations of nature and light.”)

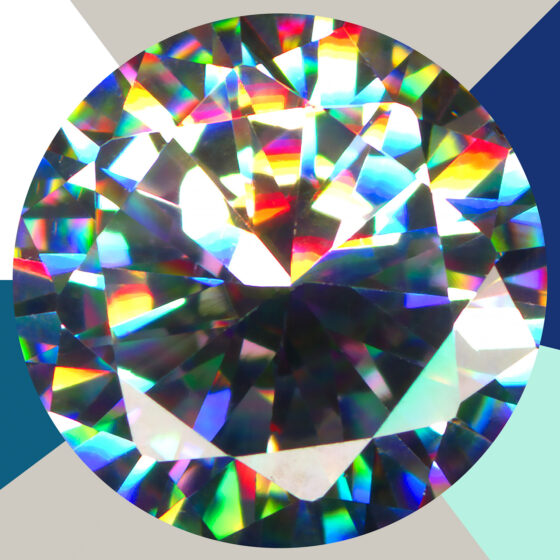

Lee’s own densely allusive visual art, which reflects on the ideas of value and forgery, feels both poignant and pertinent today. As Vancouverites know in the marrow of our bones, our home city is a spectacularly expensive place, its wealth built on the belief that it’s the best place on earth to live. We’ve seen property values yo-yo through boom-and-bust cycles, industrial areas like False Creek and Yaletown becoming affluent enclaves. We know that the appearance of wealth can, at times, be a mirage. Looking at Lee’s art, I think of young people in downtown Vancouver buying designer knockoffs from Taobao to blend in with their more affluent friends, their parents living on credit to bolster white-collar incomes. When Lee photographs cubic zirconia, as he did in Fugazi (2019), expanding the image to the length of a wall, or when his portraits feature objects purchased from dollar stores in a style that evokes the paintings of the Dutch masters, he subverts our perception of beauty and intrinsic value. In Lee’s art, Vancouverites (especially this writer, also of Chinese descent and born in 1975) see their own lives reflected.

FUGAZI (2016). 60 x 60 inches. Archival pigment print. Courtesy of the artist and Monte Clark Gallery.

Lee’s newest exhibition, Open Work (Years from Today), goes further, making us reconsider another fixture of city life as an unexpected object of worth: the Asian grandmother. In Vancouver, and in other cities with large diasporic Chinese populations, Chinatown grannies, with their distinct stooped postures and wardrobes of patterned clothes, puffer jackets, and sensible footwear, are both archetypal and unique, yet often overlooked. Lee’s intimate and whimsical show, which opens November 2 at CSA Space, foregrounds these women, setting photos of them, their backs turned to the camera, on dollar-store doilies—doilies that, like cubic zirconia, are inexpensive items inspired value and refinement.

The child of Chinese immigrants, Lee belies the stereotype of the artist as nepo baby. Originally from Guangdong, Lee’s father worked as an assayer of precious metals but studied painting in both China and Canada; Lee counts the painting books he left around the house, as well as a supportive high-school art teacher, as formative influences. While studying visual art at UBC, Lee first gained his appreciation for conceptualism and for the immediacy of photography. “I don’t think I had the patience or skill to develop anything through more traditional means at the time,” he says.

The first decade of Lee’s photographic art documents life in East Van, including a series of photos of armoured trucks, a lighted bush, and the bouquet of colours found in spilled oil on wet pavement. At other times, he stretches the definition of photography, as in his anthropomorphic images of ginseng roots captured on a scanner. And he makes us reconsider the nature of collaboration and authorship when he repurposes (and presents as conceptual art) a series of photos taken by his father in the 1950s.

“Some of these photographs were a reaction to seeing some of the high-budget photos made out there. Those photos had to do so much with privilege and access, and I frankly didn’t have a lot of that,” Lee says. Instead, he needed to seek out juxtapositions and serendipities to create “unexpected things that had value” with as little as possible.

Ginseng Root #1 (2005). 50 x 40 inches. Archival pigment print. Courtesy of the artist and Monte Clark Gallery.

Throughout his work, Vancouver, a city fuelled by privilege and access, is his stealth subject. As Lee enters the third decade of his practice, he’s become widely respected without gaining either a university job or the level of success that allows some artists to live and create without financial worry. “Just by being an artist, especially one who can’t depend on any one particular stream of revenue, I’ve been conscious about value from the beginning.”

Beyond photography, for which he’s best known, he works in other disciplines, including sculptures using instant ramen and 3D-modelled scenes of refugee boats. His paintings include a series of figurative works set in restaurants and shops that capture the melancholy of city life and of private moments in public spaces. In one, a woman stares at her phone while seated alone in the corner of a Chinese restaurant. In another, a female server clad in black stands absentmindedly by a console table.

Fortune Happiness (2018). 22 x 16 1/4 inches. Oil, pastel and pigment on canvas. Courtesy of the artist and Monte Clark Gallery.

Chinatown grannies are another aspect of city life that he turns his thoughtful eye toward. Lee’s new exhibition is a reaction to the popular coffee-table book Chinatown Pretty, an uplifting celebration of the fashion of these grannies. (One coffee shop in Vancouver has awkwardly paid tribute to these elders by decorating a wall with portraits scrapbooked from that tome.) The smiling portraits belie the “grimmer contexts” Lee has seen them in: lining up at food banks, binning in alleys, arguing in markets. He adds that he first tried to document these grannies earlier in his career, when he thought they’d disappear, but he now realizes “they are still as present as ever. They never change.”

A week after our conversation, I message Lee to ask if he sees himself in these grannies, who are often thrifty and resourceful. “I never thought of it that way but I suppose it’s true,” he writes back. “Maybe it’s the evolution: I saw them as grandma figures as a child, as peers in the present, and eventually the metamorphosis is complete when I become them!”