In the mid-1980s, Steve Martin transformed from a superstar comedian with a manic, absurdist sensibility into a respected actor in films with heart and mainstream appeal. Key to that transformation was Roxanne, the 1987 romantic comedy he wrote, produced, and starred in, filmed in Nelson, B.C.

Marking a major shift from his standup career, playing the long-nosed C.D. Bales was the first time Martin “felt respected in a film role,” according to the actor’s IMDB trivia page. Roxanne also changed the fortunes of Nelson. Incorporated in 1897, the town in the Kootenays had survived the end of the silver rush and the closure of its mill, and it was working to preserve its heritage and establish itself as a centre for the arts. On the surface, Martin and Nelson would seem as mismatched as Bales and the film’s title character. Yet with Roxanne, the comedy legend and the small B.C. town would create a classic that has endured for four decades and counting.

At the age of 12, Martin saw the 1950 film version of Cyrano de Bergerac, based on Edmond Rostand’s play about the long-nosed French noble who writes love letters to the object of his affections, pretending to be the more handsome Christian, whom she has shown affection for despite his linguistic shortcomings.

“I knew I could only play Cyrano if he were Americanized,” Martin told The New York Times. He took the idea to a screenwriter friend, David Goodman, wondering how he could tweak the story: “Cyrano gets the girl,” Goodman suggested. Martin spent several years working on the screenplay, which began as a faithful adaptation of the play before evolving into something new. As Martin writes in his graphic novel memoir Number One Is Walking, “the best way to adapt a story for a movie was to follow the course of a failed marriage: fidelity, transgression, divorce,” where at the end, “you finally separate the original and let the screenplay be what it wants to be.” Cyrano became the small-town fire chief C.D. Bales, while his love interest Roxanne (Daryl Hannah) became a grad student visiting the town to observe a comet, and Cyrano’s handsome but dim-witted rival, Christian, became the fireman Chris (Rick Rossovich).

Updating the story’s setting from 17th-century France to the contemporary Pacific Northwest was a process of elimination. “I needed a setting where people could run into each other on the street and be believable,” Martin says. A small ski resort town “was the perfect size, and everybody hung out in the same place.” In Hollywood North, Mike Gasher’s study of the B.C. film industry, he makes note of how both Roxanne and First Blood “were shot in small British Columbia communities deemed so indistinguishable from small-town America that not even their names were changed for the films.” In Roxanne, Nelson, B.C., plays the part of Nelson, Washington.

Prior to the filming, Nelson had undergone a tumultuous decade. In 1982 its chief industry, a sawmill and plywood plant, had closed, and the region’s unemployment rate was 25 per cent. Yet starting in 1979, the town began restoring its many heritage buildings. As the city’s website states, “local merchants and civic leaders developed a coordinated restoration plan and spent more than $3 million bringing the city’s magnificent buildings back to life.”

Nelson now boasts “more heritage buildings per capita than any other city in the province,” many of which feature in the film, including the famed firehouse at 919 Ward Street, where C.D. Bales serves as fire chief. On Vernon Street, Bales fights a duel using a tennis racket, while the town’s main thoroughfare of Baker Street appears throughout the film. The interiors for the bookstore were shot in Otter Books, and an eatery now known as Jackson’s Hole served as the café run by Shelley Duvall’s character. Filming also included the town of Anmore, and the interior of the bar where Bales comes up with 20 nose insults was shot in Vancouver’s Richards on Richards nightclub, which closed in 2009.

“The movie was great fun to make,” Martin writes in Number One in Walking. His only annoyance was the hour spent in makeup every day to put his prosthetic nose on—and the actual townspeople’s common refrain: “Nice nose!” At one point, Martin found himself in a “dusty saloon with sawdust on the floor,” being eyed by two bikers. Anticipating they would use the “nice nose” line, he was reduced to laughter when instead one quipped, “Why the long face?” When asked about how awkward it was to see Martin in the prosthetic, Daryl Hannah recalled, “You get used to that sort of thing pretty easily. As a matter of fact, he started looking funny without it.”

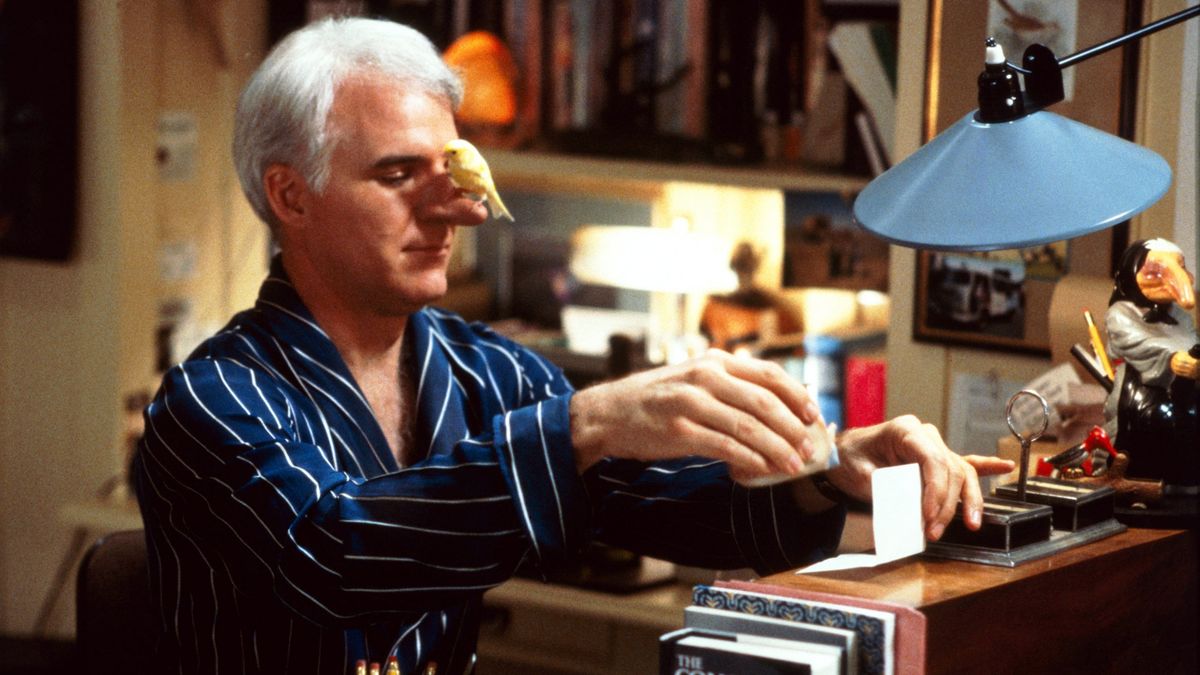

Steve Martin with his attention-grabbing prosthetic nose in Roxanne.

Roxanne was a hit, earning $42 million dollars on a small budget and enjoying enthusiastic critical praise. While Roger Ebert once wrote that Steve Martin “inspires in me the same feelings that fingernails on blackboards inspire in other people,” the critic changed his tune, calling Roxanne “wonderful” and full of “small, funny moments.” Janet Maslin also praised Martin’s performance—and nose—calling it “a perfect prop for a man who began his career with a fake arrow through his head, a man who has since evolved from a coolly absurdist standup comic to a fully formed, amazingly nimble comic actor.”

The melding of Martin and Nelson proved a heavenly match. Rolling Stone, Paste, Rotten Tomatoes, and Indiewire all include Roxanne on their lists of great romantic comedies. Martin would earn a Writers Guild of America award for his script and, in an interview with Vogue, cite C.D. Bales as his favourite role of his career. For Nelson, the film not only injected $650,000 into the region’s economy but also created a cottage industry of “Roxanne people,” tourists flocking to visit locations from the film. While other productions would be shot in Nelson, including Housekeeping and Snow Falling on Cedars, Roxanne would prove pivotal to both B.C. filmmaking and the career of its star and writer.