To say the towns of Bralorne and Bradian are off the beaten path would be something of an understatement. Four hours from Vancouver at the end of the Hurley—a treacherous stretch of logging road replete with switchbacks and hairpin turns—this one-time mining mecca (current population: 69) isn’t easy to access.

There is no hospital, no cellphone service, and few amenities. In its heyday, Bralorne was the site of the highest-grade gold producer in Canada, home to approximately 3,000 people, including colourful characters like Nosebag Jones, Slim Saunderson, and “Big Bill” Davidson. Today, the entire Bridge River valley—which comprises not just Bralorne and Bradian but also the nearby community of Gold Bridge and the lost, flooded town of Minto—is an echo of an opulent past, a region frozen in time, and an irresistible draw for urban explorers all over the province.

“People come up here because they’re interested in the gold, or interested in the history,” notes Janis Irvine, who works at the Bralorne Pioneer Museum. “There are lots of oddball things that have happened. You would be amazed at the amount of material we have.”

Before European intrusion, the Bridge River valley was the traditional territory of the Stʼátʼimc people—particularly the Nxwísten, Xáxlip, Slha7äs, Tsal’álh, and Nk’wátkwa. But in the wake of the 1858 Fraser Canyon Gold Rush, prospectors swarmed across the province, searching for the next big mineral strike. In 1865, surveyor Andrew Jamieson led a two-month expedition into the region. Early results were promising, with Jamieson writing to his superiors that he and his men were “finding gold, more of [sic] less, wherever it was tried.” Then, as now, it wasn’t an easy place to reach, with Jamieson noting that “By the time we got to the place w[h]ere we intended to operate, it was almost time to turn round and go back.”

A subsequent expedition, undertaken in 1897 by William Young, Nat Coughlan, and John Williams, was equally punishing. These early prospectors were well rewarded for their tenacity—all four staked claims that would later be developed into the lucrative Pioneer and Lorne mines. However, owing to the difficulty of the terrain, it would take decades for the proper gear to be available, and initial efforts to bring in milling equipment were outright laughable.

“The driver threw off package after package,” early resident J. Edward Norcross wrote, “but no mill appeared … At last it was reached and, as one bystander observed when the general laughter had subsided, it was just big enough to make a good-sized coffee grinder.”

Although the mines changed hands a number of times in the ensuing years, they remained small-scale operations until the late 1920s. Then, a series of purchases and mergers spearheaded by Bralco Development brought the Lorne and Pioneer mines together with several nearby claims and camp buildings. As was common at the time, the resulting townsite was named after the newly formed company: Bralorne. Even before Bralorne Mines Limited poured its first ingot in March 1932—worth approximately $6,000 ($131,000 today)—the region’s resource boom had begun.

“Mining in British Columbia has withstood the shock of world depression and extreme low metal prices in a most satisfactory and remarkable manner,” William Alexander McKenzie, minister of mines, beamed in a June 1931 statement to the Victoria Daily Colonist. “Unemployment and the lure of gold—again a potent attraction—has resulted in many men going into the hills, with the result that more are so engaged than in the year 1930.”

“Everybody was coming here,” Irvine explains. “It was the Depression. This was the only place in the province where there was work.”

Even with its sudden prosperity, Bralorne was still very much a work camp in the early 1930s. But, as the boom years went on, it grew into a bona fide town, boasting a British Columbia Telephone Company office, an apartment house, a church, a school, and a doctor’s office. Conditions were rustic, and at an elevation of approximately 3,500 feet, the winters were harsh. But as early resident Clara Lambert recalled, the workers excelled at making their own fun.

“In the centre of the [cookhouse] stood an old oil drum for a stove,” she explained to the Bridge River-Lillooet News. “On Saturday nights we would all get together for a few good old square dances. The orchestra consisted of four instruments—violin, played by Van Smith; traps, by Jack Williams, who beat a mean drum; and sax, by McCandlish, who could make Benny Goodman blush. Ohmer, my girlfriend, used a wicked bow on her violin, which made the bumble-bee take flight in shame.”

News of the Bridge River mines appeared consistently in B.C.’s papers throughout the 1930s, and as their fortunes rose, the population of the region swelled dramatically. Just a few kilometres down the road, prospector “Big Bill” Davidson founded the townsite of Minto, even importing his own soil to build a rodeo site and baseball diamond for prospective employees. “I’ve got pictures of those houses in 1937, and they look like the American Dream,” Irvine says. “They’re clean, they’ve got little windowsills … white picket fences and all this stuff.”

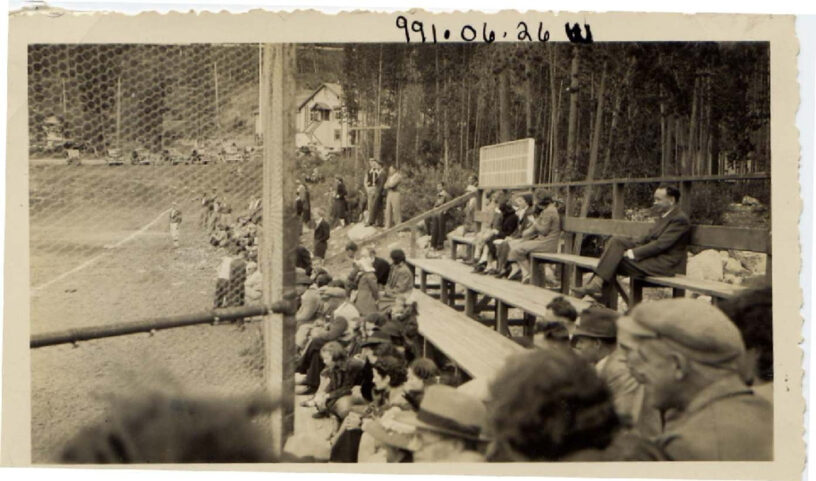

Spectators watch a baseball game in Bralorne, 1935. Image courtesy of the Bralorne Pioneer Museum.

But as the other sites prospered, Minto was an early casualty. Despite Big Bill’s blustering, it ceased operations in 1940 due to poor mineral showings. However, Minto continued to be inhabited, especially after the federal government forced B.C.’s Japanese Canadians into internment camps in 1941. In some cases, wealthier families were allowed to escape the camps by paying for the cost of their own internment, letting them move to communities like Minto, where the intact homes, shops, and infrastructure provided a space for families to retain some semblance of normalcy.

Nonetheless, it wasn’t an easy life. “Those of us sent to East Lillooet, Bridge River and Minto supported ourselves without government assistance,” writes Dale Johnston, whose family was interned at Minto during the war. “Upon arriving in Minto, our family’s austerity program commenced. Forthwith, Mother sought employment with [Big Bill] Davidson cleaning his house. She also did laundry on a washboard for the owner’s General Store. Her work brought food to our table in the form of $0.15 worth of bologna. Vegetables from the garden augmented our diet.” Like all Japanese Canadians, Johnston and her family remained interned until 1949.

A Minto school class, sometime in the 1940s. Image courtesy of the Bralorne Pioneer Museum.

A decade later, the town was wiped off the map when the valley was flooded as part of a provincial hydroelectric project—a development that came as an unpleasant surprise to Big Bill. “When he had the papers drawn up by his lawyer, the documents were sent to the Land Titles Office in Victoria,” Irvine explains. “And there were no encumbrances on the land at that time … And they come across this one. And they go, ‘Uh oh.’ Suddenly, they slap an encumbrance on him. And they take his timber rights away. And they have the right to flood.”

With details surrounding the government’s claim to Minto scarce, Irvine says some Bridge River residents believe that Davidson was the victim of government trickery. However, her own research indicates something less sinister. “This was during the Depression,” she sighs. “How many people were in the office at that time? All these papers are piling up on somebody’s desk … Somebody made a mistake somewhere. And he paid for it.” Today, only the barest hints of Minto are visible—building foundations alongside rusted cars and farm machinery.

Meanwhile, Bralorne continued to be profitable. By 1948 ,the combined value of the Bridge River mines was listed at $5 million ($65 million today). In 1954, the population stood at around 1,700 people—significant enough that Bralorne expanded, and the nearby townsite of Bradian was built. The 1960s and early ’70s saw a reduction in operations and employee numbers. As other mines shut down, and the townsites nearby slowly disappeared, the Bralorne Mine continued to operate until it was the only one left. By the time it closed in 1971, it was the last gold-producing mine in British Columbia.

“This famous old gold mining town is still breathing,” the Vancouver Province wrote in September 1971, “but the end is near.”

By then, as is typical of resource towns across North America, the communities they had supported were virtually abandoned. Bradian emptied out nearly as quickly as it had filled up, and many of the houses were left to rot. “Eighty percent of the housing has been vacated and much of it was vandalized immediately,” the Province wrote of Bralorne. “Windows are broken within 24 hours of houses being vacated. Plumbing and electrical items are torn out and the remainder smashed. Nobody seems to know why, or know where the vandals come from.”

Bralorne Main Street, 1938. Image courtesy of the Bralorne Pioneer Museum.

Although there was talk among management of selling the remaining homes for salvage or burning them to the ground, most were simply abandoned. Since then, Bralorne and Bradian have become something of a magnet for outsiders with big dreams. In 1972, they were purchased by the Whiting brothers, who renovated some of the existing buildings, hoping to sell them as recreation and retirement properties. The plan drove them into bankruptcy. There was talk of a hippie commune or of using one of the old mine shafts to grow mushrooms. These also failed.

Despite rumours it was empty, Bradian had two full-time residents until the 1990s—one of whom had inherited the entire community from her mother. After they died, the area was in serious danger of disappearing: of the 80 homes that remained when the mine closed, roughly 50 were disassembled by Bralorne residents and used as materials for their own houses. Bradian continued to decay until Tom and Katherine Gutenberg—flight attendants with Air Canada and history buffs—bought it in 1997 for a mere $100,000. Over the course of two decades, the Gutenbergs and their children worked to restore the remaining homes, adding tin roofs and repainting.

When their restoration efforts had progressed as far as they could, the Gutenbergs sold to developers China Zhong Ya Group—another in a long line of wealthy interests that saw Bradian as a money-making opportunity—for almost $1 million. Seven months later, the company relisted the site for sale.

Today Bralorne, with its 69 residents, remains inhabited but in decline, with many of its homes and buildings listed for sale. Outside of town, Tyax Lodge caters to alpine enthusiasts, offering heliskiing as well as float plane excursions to those willing to brave the Hurley (considered by some to be the worst-maintained road in British Columbia). But Bradian remains empty—a ghost town.

The redone roofs and bright paint jobs left behind by the Gutenbergs give it an eerie feeling. Although porches and staircases may have collapsed, and the floors are a tapestry of detritus— broken glass, rat turds, and the remains of a rug or two—stepping across the threshold into any of its abandoned homes feels like trespassing. Some cupboards still contain dishes, and one house has a metal trash bin in the backyard.

As of 2024, the Bralorne Mine complex is owned by Talisker Resources, which began test mining in the second quarter of the year and is billing the project as “Bralorne Re-Imagined.” The future of the area is uncertain, but for some, like Janis Irvine, there is hope that Bralorne will see renewed prosperity, and that its quiet charm and natural beauty will be appreciated by a new generation.

“Bralorne is like Pemberton was 20 years ago,” Irvine muses. “I think it’s going to go up, and up, and up. People want property, and the young people want out of the city. If we had medical and dental a little bit closer, you’d see this place pack in like you wouldn’t believe. And I think it’s going to happen.”

Read more local History stories.