For half a millennium, the Forbidden City, the largest enclosed palace complex in the world, was inaccessible to the public. What lay beyond the vermillion walls, nearly eight metres high, could only be imagined. Just over a decade after the dissolution of the Qing dynasty, Beijing’s Palace Museum was established in the Forbidden City in 1925, opening the palace doors to all and attracting both local and international tourists. Today, short of journeying 8,510 kilometres to Beijing, Vancouver is privy to a special opportunity: an exhibition of nearly 200 artifacts from Beijing’s Palace Museum offer a rare glimpse into life in China’s storied imperial palace.

“The Forbidden City: Inside the Court of China’s Emperors”, presented by the Robert H.N. Ho Family Foundation and CNOOC Limited, runs October 18, 2014 until January 11, 2015 at the Vancouver Art Gallery (VAG). The exhibition was organized by the Palace Museum in collaboration with the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, where it premiered this past March.

The Forbidden City was completed in 1420, after 14 years of construction, which is said to have involved a million workers and countless artisans. It was first the seat of the Ming dynasty, followed by the Qing; it was the home of the emperor and all who served him, as well as the administrative and political headquarters of his empire. It was, on all accounts, a stage for the display of wealth and power.

From the physical orientation and layout to the individual sculptures and objects within, the Forbidden City is deeply metaphorical in nature. The VAG exhibition leads visitors into this long verboten realm and on a symbolic journey from the Outer to Inner Court through nine thematic sections in the gallery. Upon entering, three great emperors of the late 17th and 18th century are introduced in portraiture: Kangxi, his son Yongzheng, and his grandson Qianlong. “These three men really defined what China became by the time it entered the 20th century: wealthy, and powerful,” coordinating curator Timothy Brook explains. “In the 18th century, this was the most powerful state in the world, and it had the largest territorial reach of any empire.”

The Forbidden City was completed in 1420, after 14 years of construction, which is said to have involved a million workers and countless artisans.

One section of the exhibition, “Reigning”, displays the emperor’s throne within the Forbidden City, and the surrounding objects and icons that represent and reinforced his power. (It takes an hour and a half to walk from the South Gate to the North Gate of the Forbidden City, unless you were the emperor, in which case you were carried on a sedan chair by up to 16 eunuchs.) Ceremonial armour and weaponry in “Warring” show how the emperor’s reign was enforced. And “Symbols” is an exploration of iconography. Only the emperor could wear yellow, and only the emperor could wear a dragon on his robes. This didn’t prevent common folk from donning the revered symbol, however. “Designers got around this by removing a claw from the dragon’s feet,” Brook says. “Since dragons have five claws, a dragon with four claws isn’t a dragon, it’s something else.”

Beyond the Son of Heaven’s presentation to the public in the Outer Court was his more personal and private life and responsibilities, which took place in the Inner Court. The objects in “Lineage” speak to the life of women in the Forbidden City, including that of the notorious and formidable Empress Dowager Cixi, the original “Dragon Lady”, who unofficially controlled the Qing dynasty for nearly 50 years; the dynasty collapsed three years after her death.

Duties aside, the emperor also engaged in other recreational activities, including poetry, art, hunting, and collecting; various objects in the exhibit speak to these, such as Book of Emperor Qianlong’s poems, Series 1, Volume 2 (1736–95) and specimens created during other eras such as the Ming and Yuan dynasties. “Running an empire isn’t just doing the business of government, it’s walking through rituals constantly,” Brook says. “There were rules for everything the emperor did, and the best emperors performed these rules effortlessly. Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong took ruling very seriously. It’s a matter of being able to wage war, run an administration, and then make sure you are in touch with the forces of heaven.”

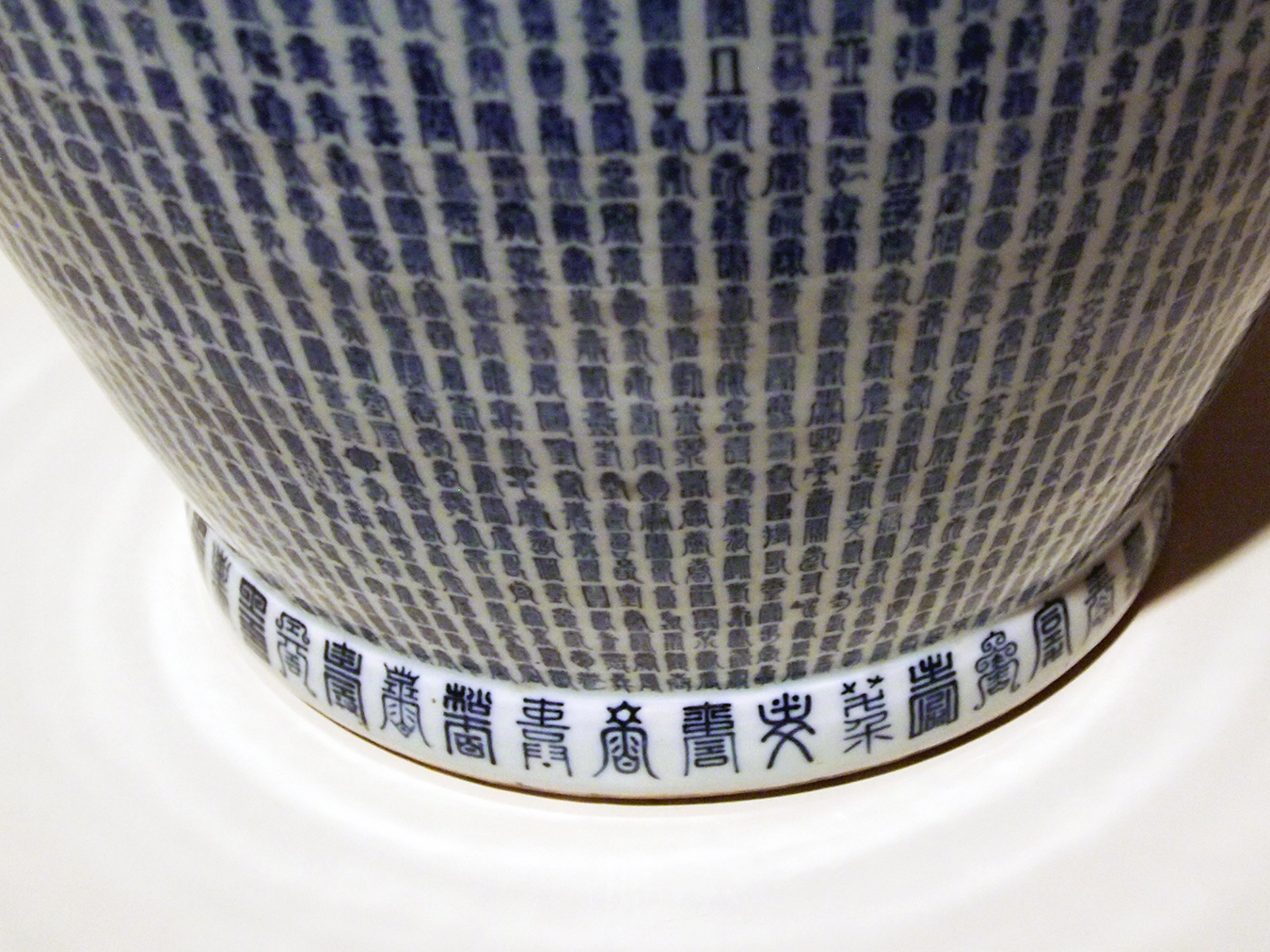

The exhibition’s final artifact is Jar with Ten-Thousand Shou (1712–13), a gift to the highly-regarded emperor Kangxi on his 60th birthday. The porcelain vase is decorated with the character 壽, or longevity, written 10,000 times in 975 different calligraphic styles. It is, essentially, wishing the emperor 10,000 years 10,000 times over. The wish for eternity is a fitting tribute to the Chinese imperial system, which endured thousands of years of change before finally collapsing, but not without leaving a legacy.

Photos by Kristin Ramsey.