People browsing through Vancouver record stores might notice a curious phenomenon: several of the most exciting reissues of vintage Vancouver bands have been on a Los Angeles-based record label called Porterhouse Records, including albums by the Modernettes, the Pointed Sticks, and the Young Canadians, as well as digital-only ones by Los Popularos and Art Bergmann. There are also Vancouver-adjacent releases on Porterhouse by Personality Crisis (R.I.P. Jon Card) and the Dils (R.I.P. Zippy Pinhead).

Worthy as all these bands are, it’s an unusual amount of Vancouver content for an indie American label to boast. So what gives? The answer is Steve Kravac, who runs the label. Turns out that Kravac went to high school in North Burnaby.

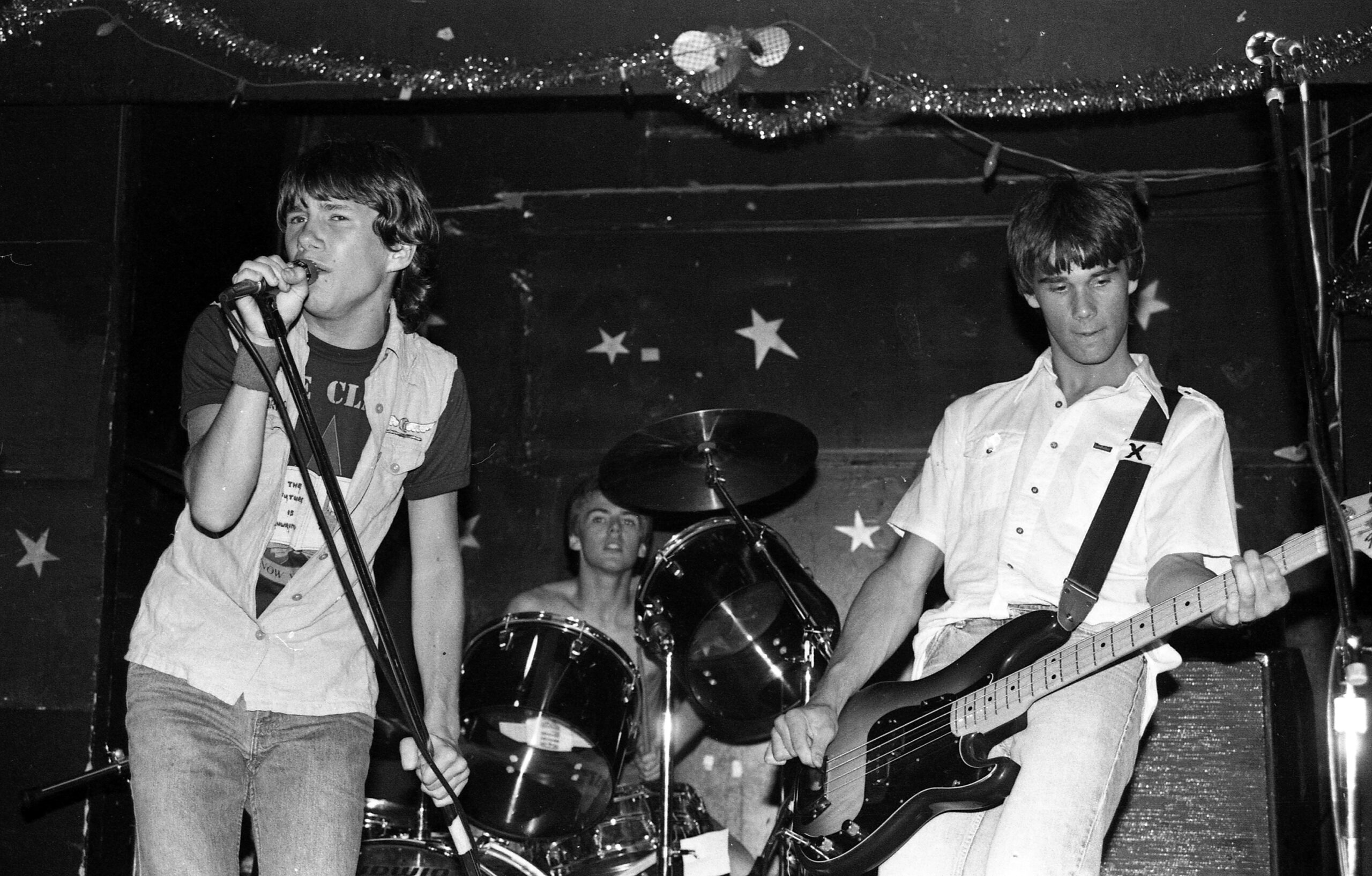

“It was the same place Joey Shithead—Joe Keithley—graduated from. He was class of ’78. I’m class of ’82,” Kravac tells me over lunch at Chongqing on Commercial Drive during one of his regular visits here. “I grew up in Vancouver, in a punk rock band called Social Outcasts, with Mike Usinger from the Straight [on bass]. We were best friends in high school.”

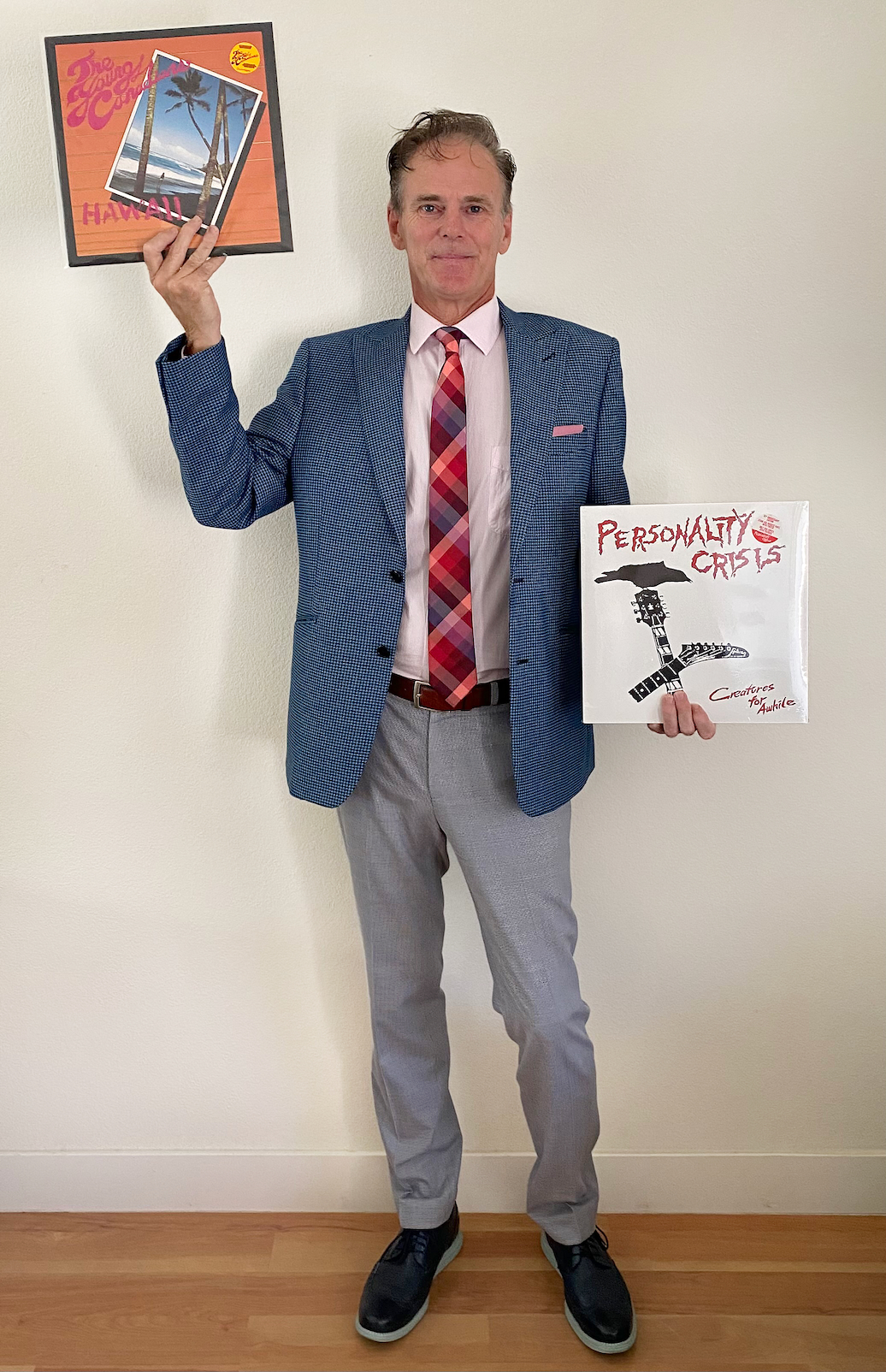

Steve Kravac holds two Porterhouse releases.

The majority of Social Outcasts’ songs online are from later versions of the band, but the Usinger and Kravac rhythm section can be heard in a demo version of a song Kravac wrote, which was recorded at what would become Profile Sound Studios, in sessions presided over by Ray Fulber and Billy Barker of the Vancouver pop-punk group The Scissors.

That was Kravac’s first taste of production close up, spurring an interest that would follow him to Montreal, where he went shortly after graduating from high school. Social Outcasts would continue without him.

While in Montreal, Kravac drummed for My Dog Popper and got involved with a campus radio station at Concordia University, CRSG, where he started doing some engineering: “I got into the studio and realized I really liked this stuff.”

Within a short period, he had a recording studio of his own in his downtown loft. “I pushed a ton of local bands through there,” he recalls, including several noted Canadian punk bands, from the Asexuals and the Doughboys to S.C.U.M., whose Born Too Soon LP would later be reissued by Porterhouse. Within a few years, “I had enough of a reel that when I decided it was time to make a move, I had something I could play for folks.”

Opportunity knocked in the form of the Northridge earthquake of 1994, when the house engineer quit at Los Angeles’ Westbeach Recorders, a studio co-run by Brett Gurewitz, the founder of Epitaph Records (and Bad Religion guitarist). “Westbeach was known as punk rock central. That’s where people went for that sound,” a clean, bright, precise version of punk that was promulgated on Vans Warped tours.

At that point, Kravac had been doing live sound with the American punk band Youth Brigade. One of the band members, Mark Stern, called Kravac’s resumé to the attention of the Westbeach honchos, saying to them, Kravac recalls, “Hey, look at this resumé. This guy knows what he’s doing. He gets great sounds.”

Kravac was hired, and for the next few years, he produced, engineered, and/or mixed bands such as NOFX, Voodoo Glow Skulls, Less Than Jake, and Blink-182, then just called Blink. He made two records with legendary MC5 guitarist Wayne Kramer, starting in 1995 with The Hard Stuff. And he got involved with a Christian punk label called Tooth and Nail, earning a gold record (500,000 sold) for an album on its roster, MxPx’s Slowly Going the Way of the Buffalo.

“It had a bona fide radio-hit called ‘I’m Okay, You’re Okay,’ which played on KROQ in L.A. and stations all over the country.” All the while, Kravac was studying Gurewitz’s example when it came to Epitaph.

“Brett is an astute businessman and a very smart individual. I thought, ‘I’ve got decent taste. If Brett can run a label, I can run a label. Let’s see what happens.’ That’s how Porterhouse came into existence.”

There were some growing pains, false starts, and complications, including a falling out with a partner he’d prefer not to mention. And not many of the bands Porterhouse released in its first 10 years had huge names (Rosemary’s Billygoat? Never heard of them). But Kravac was still finding his path, figuring things out from the ground up. “What do you do? Where do you press? How do you get artwork done? I had to put all the building blocks together from nothing.”

After a couple of years, he saw potential in reissuing vinyl originally put out by other labels. “One of the bands I realized didn’t have anything out was X, so I approached Warner Brothers about their initial run of records,” between Los Angeles and More Fun in the New World: “‘Look, you control these records. None of them are on vinyl. Do you want to issue licences?’ And they did. So I kind of kicked off the real, I guess, more ‘legitimate’ and ‘professional’ Porterhouse Records by licensing those X records.”

Related stories

- Behind the Camera With Bev Davies, Vancouver’s Original Punk Photographer

- How Godspeed You! Black Emperor Came to Feature a Vancouver Street Preacher on Its Debut Album

- Dead Bob, Nomeansno, and the Punk Ethos of Vancouver Musician Kristy-Lee Audette

That would have been circa 2010. “That was like the door opening. We’d ship those records out, and nothing would come back. There were no returns, because vinyl was just starting to have its rebirth. I worked with the band on those reissues, and I did a box set of their first four records and created a 20-page booklet. I contacted Ray Manzarek [still best known as the keyboard player for The Doors], who produced those records, and got him to write a foreword.”

Manzarek died a short while later, and the box set may well have his final public words on those records. “That was one of the craziest things that ever happened: you’re picking up your phone one day, and there’s a voicemail from Ray Manzarek, saying, ‘Hey, man, I hear you’re doing a box set. Tell me more. What do you need?’”

Kravac had such reverence for the original recordings that he would go personally to band members’ homes, visiting X’s Exene Cervenka, for instance, to show her scans of her artwork. “I made sure she had input on everything we did. I worked hand-in-hand with them, because for me, everything had to be absolutely perfect.”

With the success of the X reissues, Kravac was hooked: what records had he loved as a kid that weren’t in print in vinyl that he could get licences to reissue? Subsequent Porterhouse releases include the Gun Club’s Fire of Love (“the best-sounding vinyl cut of that record that was ever made,” Kravac says) and Urge Overkill’s Saturation (“I think it is one of the most significant and best-produced albums of its era”), which also sounds great as a Porterhouse reissue.

“The majors have so much intellectual property that there’s no way they can put it all out themselves. They need partners like Porterhouse that know what they’re doing, that have the technical expertise, and that understand how the artwork has to be created, to partner with them.”

“Artwork is something that I take just as seriously as pressing,” Kravac says. “Most of the Porterhouse releases contain some sort of insert. Why? Because when I was a kid and I opened up a record, those are the things that I loved.”

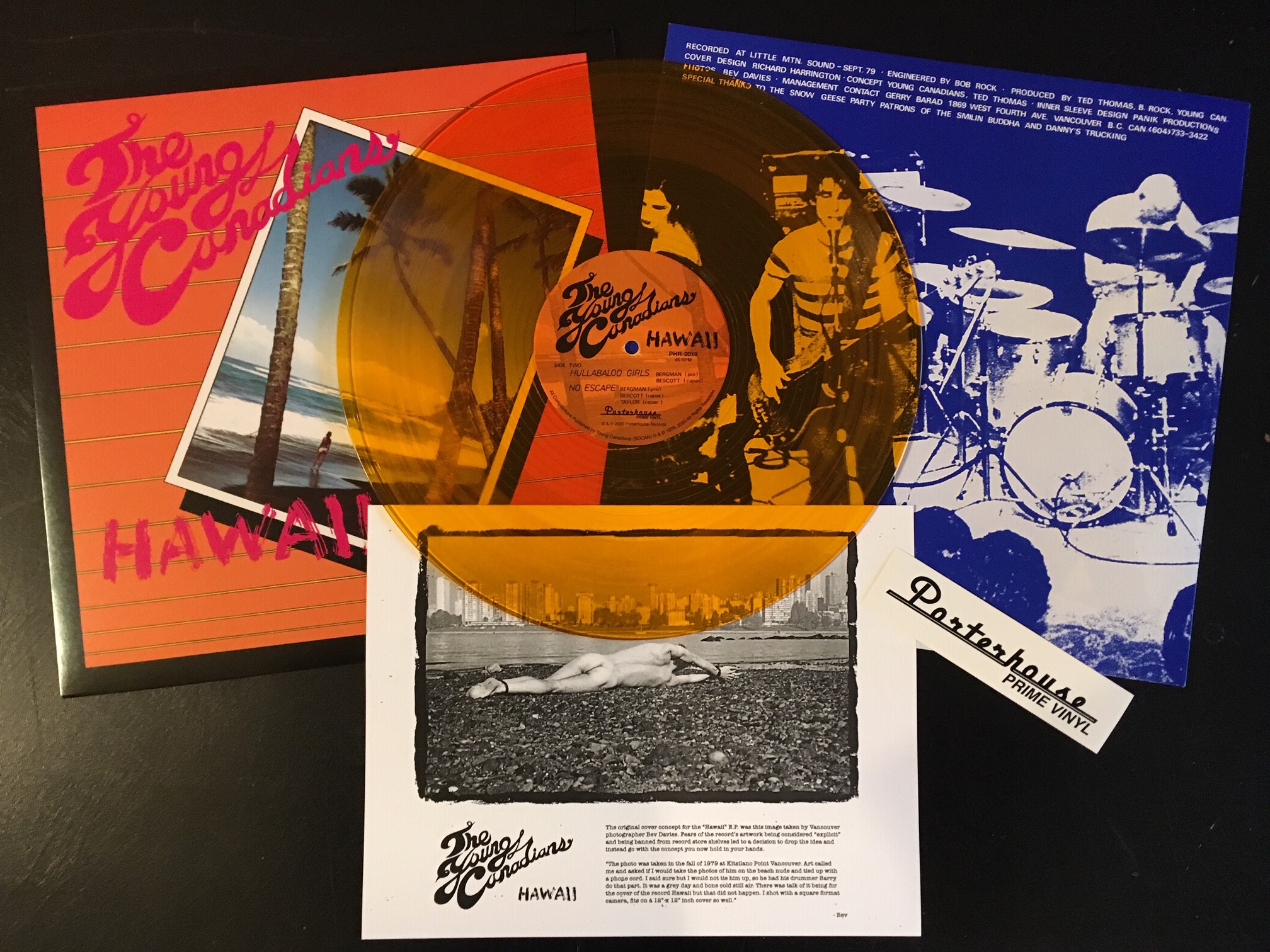

This writer’s favourite Porterhouse reissues so far are the Young Canadians’ Hawaii and the Modernettes’ View From the Bottom, both of which sound terrific, but it’s really the art that, in both cases, wins me. Porterhouse’s Hawaii includes as an insert Bev Davies’s original 1979 shot of Art Bergmann bound naked on a beach at Kits Point, with early Yaletown highrises visible in the distance, as if he is in bondage to real estate developers. It was intended for the album cover, but its original label, Quintessence, got skittish. The Porterhouse reissue marks the first wide commercial availability of that image.

Even better, the Modernettes’ View From the Bottom reproduces, for the first time, the hilarious—and brilliant—cover art of the original, with an image lifted from Sunset Boulevard on the front cover and a back cover boasting frontman John Armstrong’s—A.K.A. Buck Cherry’s—TV Guide-style spoofs, which identify each song as if it were a capsule description of a late-night movie. “Static,” the album’s most adventuresome venture into post-punk angularity, is described as being about how “a Mad Scientist (John Carradine) plots to destroy Los Angeles with sonic waves.” Better still, “Red Nails,” actually titled after a Conan story, is purported to be the title of a Jean-Luc Godard film about the life of Christ. Of course, neither film exists.

And even if you own the original of that album—a pricey collectible—there’s good sonic reason to pick up the repress.

“John was incredibly disappointed with how that record turned out technically” back in 1982. “He’s spoken about that , and it’s in print” (to me, in fact, in Big Takeover #93). This fits with Kravac’s own memories of the record, which he confirmed when he sat down to prepare a new master, ripping from vinyl. “Three of the songs on that record, the drums are in phase, but two of them they’re out of phase.” There’s also no low end and too little sibilance on the high end, Kravac noted. Without a master tape, it was up to him to correct the sound as best he could.

“I ripped the vinyl into digital, and I re-EQed it through a couple of pre-amps, and I tried to give it what I always thought it missed when I was a child. When John got my reissue of it, he said, ‘I don’t know what’s happened here, but whoever has looked at this understands that there was a problem. It now sounds pretty darn close to what we expected to have.’ That’s the greatest compliment anybody could give me, that you have exceeded the original. We realized there was something wrong, but we were never sure what it was. You’ve made it better. There’s no better comment that an artist could make.”

More recently, Kravac has issued the Modernettes’ Teen City, which, unlike View From the Bottom, had no technical issues whatsoever. It comes with coloured vinyl, exclusive art, and liner notes, as does the Pointed Sticks’ Perfect Youth, which, like Hawaii and Teen City, was originally produced by Bob Rock. Kravac consolidated the artwork from the original on one side of the insert and created a new flipside, featuring an essay from Big Takeover publisher (and fellow vintage Vancouver punk enthusiast) Jack Rabid, with photos of the band by Steve Josephson that nobody has ever seen before.

“Those are the kind of things that, when people go, ‘Why did I just pay $32 for this record,’ when they open it, I want them to see that their money was well-spent, that there’s value added, that somebody was actually thinking about doing something to elevate the product to another level and create a new experience.”

Pointed Sticks vocalist Nick Jones, a known stickler for quality, is delighted by the reissue, saying it looks and sounds amazing (“I love the orange,” he adds, referring to the cheery splatter-vinyl).

As for Kravac, Jones—no stranger to rock merchandising, which was his day job for decades—offers that “He’s a top man. I love his attitude towards the biz. He’s an old-school huckster: 50 years ago, he’d have been driving across the southern states in a jalopy with the trunk full of records to sell.”

Jones is joking, but Kravac truly does have the DIY ethos of punk down pat. If you write with a complaint or a suggestion, it will most likely be Kravac himself who answers. “That’s how I like it: everything with Porterhouse remains under in my control. I don’t like to delegate too much. I want to know what’s going on.”

And when he’s in Vancouver, Kravac, who maintains his Canadian citizenship, personally goes from record store to record store, dropping off vinyl. When he finds out about a store he doesn’t know, like the recently established Matterhorn Records, which I mentioned to him during our interview, he makes a point to check it out, building relationships in person. Meantime, when he’s out of town, he sometimes enlists the aid of his mother, Grace, A.K.A. “Porterhouse North,” who is 90 this December and will run records to Neptoon or Red Cat as needed.

With tariffs and political turmoil down south a constant concern, Kravac makes sure Canadian customers can get hold of his product without shipping from the States. His website features, on the right side of the top banner, a button to allow you to find a store that stocks Porterhouse releases near you.

One album remains to be dealt with, perhaps one of Porterhouse’s more obscure titles: Steven Bradley’s Summer Bliss and Autumn Tears. The song boasts gorgeous popcraft and is an obvious labour of love, with layered, nuanced production and the sort of sonic detail that warrants breaking out the headphones. So who the heck is this Steven Bradley, and why haven’t we heard of him before?

It is, of course, Steve Kravac, recording under a pseudonym. “I didn’t want to have the work immediately compared to what I did as a producer. Up until that time, that’s what folks knew me as.” He does give himself a producer credit under his real last name on the back cover. Choosing the pseudonym Steven Bradley—based on his own real middle name—was “helpful in freeing myself from my own past and its ingrained viewpoints and patterns. I wanted the record to be a freeing expression in many ways.”

Once you understand who Steven Bradley really is, the song “Capitol Hill” becomes even more poignant. That’s not the Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., where the singer had his first kisses and rode his bike into the night. It’s Capitol Hill in Burnaby.

The song is maybe a bit bittersweet in its nostalgia, with Bradley—that is, Kravac—singing about how he’s “given up looking for the treasure” he buried. But all things considered, we’re not so sure we believe him.

Read more stories about Vancouver’s punk scene.