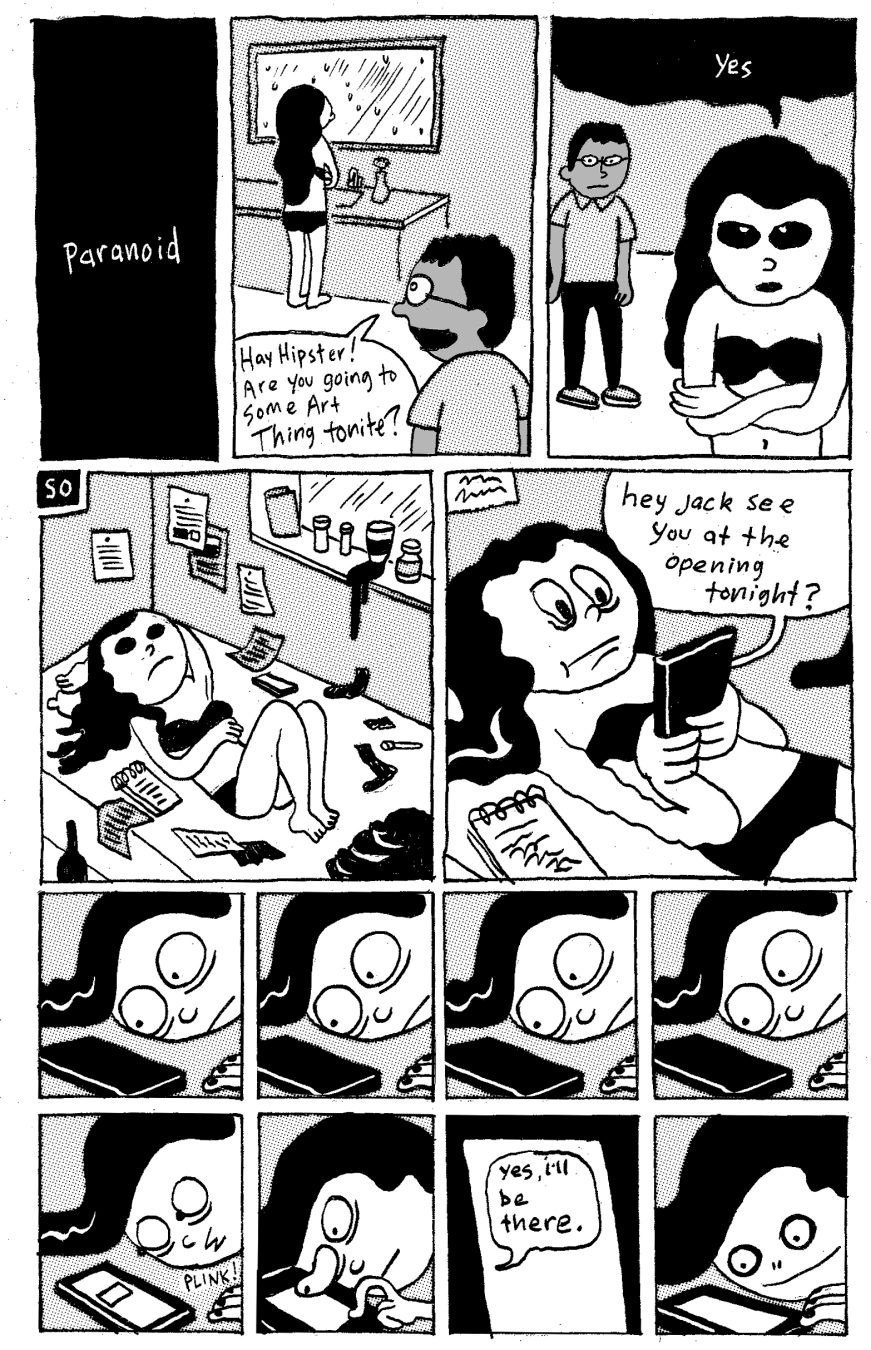

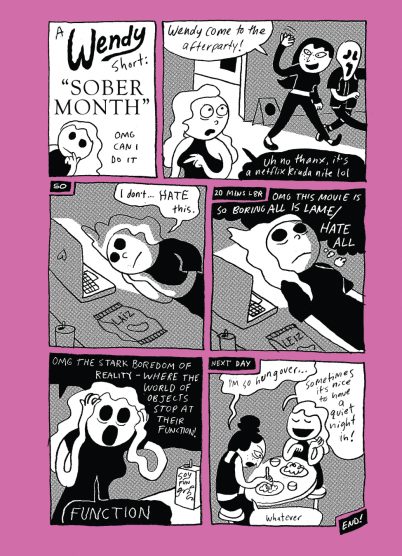

Wendy: she’s pretty, funny, and always dressed really cool. She’s also a bit of a mess—her art is good but she’s easily seduced by boys in bands, cheap beer, and the promise of drugs, so she has a bit of trouble getting her Canada Council grant applications in on time. If you’ve ever attended art school, a gallery opening, or a hip warehouse after-hours party, you’ve probably met Wendy. And if you’ve done all three, there’s a good chance you are Wendy.

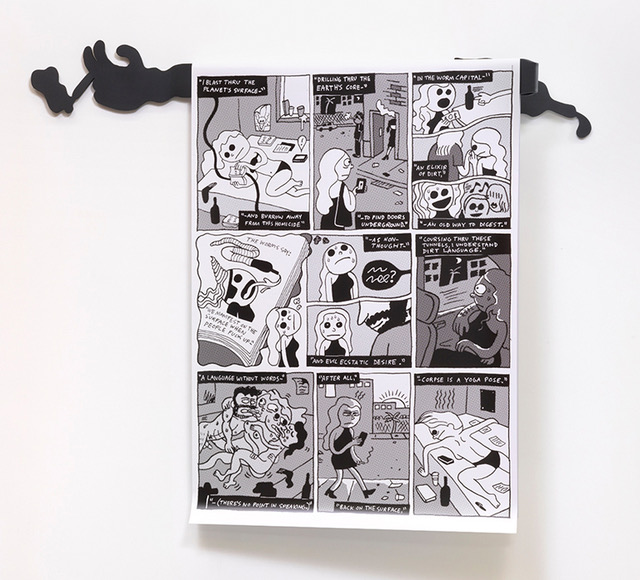

Walter Scott’s uncomfortably relatable comic book character has been making art kids laugh, cry, and cringe since he first introduced her in 2011. He has also published two books with Koyama Press to both a dedicated cult following and critical acclaim. (A close read of the shoes that appear in the Wendy comics is particularly illuminating.) Scott’s most recent book, Wendy’s Revenge, was released late last year, and chronicles Wendy’s move from Montreal to Vancouver. Scott, who is currently based in Ontario pursuing his master’s of fine art at the University of Guelph, was in Vancouver just before the opening of his solo exhibition, “A Small Metal Crow with Wings on the Way”, at Macaulay & Co. Fine Art. The show, which runs until April 15, 2017, centres on his studio practice and is heavy with comic book references (Snoopy features prominently) while simultaneously addressing issues surrounding identity and cultural representation.

Explain a bit about how you came up with Wendy.

I drew Wendy on a place mat when I was living in the Saint-Henri neighbourhood in Montreal. It initially just started as a way to make myself and my friend who was sitting there laugh; she was kind of an avatar of my own extensional angst at the time.

It was a couple little Wendy comics, and all of a sudden I started seeing that there was a narrative starting to form and a character starting to take shape. So I filled in the cracks and made a whole 60-page book, and then I self-published the book and I sold it at the zine fair in Montreal. I was really excited to do something that felt really personal, because before that I felt like I was trying to squeeze my way into the art world, and that was always really frustrating. This project was the first thing I did that felt purely for myself without feeling pressure to conform or please anyone else.

How do you navigate having both the gallery art practice and Wendy? Do you feel they’re related to one another?

I used to feel the pressure to differentiate the two, but I realized just in the last few months I just wanted to make things that I like. So now the drawings that I do and the objects that I work on outside of Wendy, they more obviously reference my comic book aesthetics and my innate instinct to draw. So, I’m trying to more obviously integrate that into everything that I do because I can’t escape it anyway. I’m less afraid of making weird things; where maybe before I felt this pressure to create things in the context of a white cube, now I don’t care as much.

Do you find that there’s an expectation now of you including Wendy in your gallery work?

I had one person say that some of my works didn’t have the sense of humour or the self-reflexivity of being artworks, in the way that Wendy has that self-reflexive quality of the self being the satire of the art world. They were like, “Where is that self-awareness in your structural practice?” Which I guess is something I have to think about. That pressure, it’s important to not pay attention to it sometimes, because it’s so wrapped up in potentially discriminatory or exclusionary ideas around art.

There’s a lot of Wendy that’s based in relatability, but there’s also that fine line between relatability and satire, or maybe parody. How do you view those intersections?

I think Wendy is painfully relatable to a lot of people, but she also has a lot of weird free passes and privilege in the narratives that make her unlikable in a lot of ways. That’s kind of contrasted in the stories with characters like Winona: she’s an Indigenous character, so you see Wendy’s privileges in context and in comparison, in how they may affect somebody. In Winona’s subjectivity, you see how Wendy is potentially not perfect, or how who she is actually potentially oppresses other people.

Was Winona a foil character that you wanted to develop to highlight those differences?

Yeah, because when I made the first Wendy I all of a sudden realized, “Oh she’s like a white woman.” And if she wasn’t a white woman, this kind of blank slate of the typical white gallery girl, would people have paid attention initially? If she was very overtly Indigenous, would people have filed it away or put up a wall of defense because they automatically assume those kinds of narratives are in opposition to their subjectivity, especially if it is a white readership?

I realized there was some kind of weird Trojan horse scenario happening where I had somehow infiltrated, not maliciously, but had someway created a very relatable character that didn’t have these particular ethno-cultural markers. And I thought that it was a perfect place, now that people are paying attention, to inject a character that does, and have a person be confronted with a character who is in relation to Wendy in the same way that I feel my Indigenous identity is in relation to the art world. So I thought it would be the perfect opportunity to have that person in print, and you can’t escape the character—she’s part of Wendy’s life. If you relate to Wendy, you kind of have to go along the journey of being in relation to this Indigenous person.

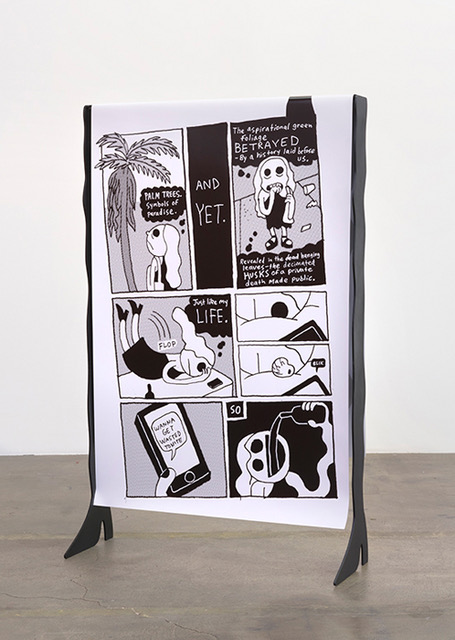

Those similar themes are taken up in your second book: there are some more artistic liberties taken when Wendy goes to Japan, where some of it is translated and some isn’t.

There’s one chapter that’s in English, Japanese, and Mohawk, which is my ancestral language, but I was interested in making something inaccessible to the audience that would otherwise assume was for them. Because they relate so deeply to all of the other Wendy material and can understand it, I think people suppose that all the Wendy material should be accessible. For me, with my Indigenous identity, I went to primary school entirely in my language, and as time went on and I moved to the city, I lost touch with it. And feel like the language is inside of me somewhere, but it’s like looking at the language through a foggy window. It’s a weird cognitive dissonance to feel that something is yours and belongs to you, but you can’t access it. So I thought to make a Wendy book where an entire readership of English speakers suddenly are confronted with something that is relatable and theirs, but they can’t understand it. It’s because I want them to understand what that feeling is like.

It seems that you really have multiple ways of relating to the character of Wendy.

Yeah, it’s true. Sometimes I find myself grafting a weird gay male neurosis around sexuality on Wendy that doesn’t exactly match, and I’ve had people be like, “So, the thing Wendy did there is such a dude thing, like women don’t do that kind of thing.” But then I’m like, “Well, maybe some women do?” It’s interesting to know what of her anxieties are more gendered than others, and what exactly does that mean for my anxieties?

Do you ever find yourself trying to find what Wendy’s perspective would be? Or is it all yours?

When I first started Wendy it was a one-to-one of how I would react to things Wendy does, and I think it’s still like that. She’s inextricably tied to my emotions. I found sometimes I would put myself in situations because I thought it would make a good story, but I try not to do that anymore because I’m already narrating my life as it happens.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

More from our Arts section.