Today, there is scant information about the occupant of Suite 1030 in Vancouver’s iconic Marine Building. No business name. No listed occupant. Just a simple suite number, and an awkward silence from management at the Oxford Properties Group.

But back in the spring of 1932, it was infamous.

On April 1 of that year, Suite 1030 became home to the newly formed Vancouver Birth Control Clinic—the first women’s sexual health clinic in the province, and only the second in all of Canada.

It was a place that flew in the face of convention; run by women, for women, it happily thumbed its nose at the laws of the day by providing contraception and education to the city’s low-income population. And what’s more, it owed its existence to a combination of factors that will sound all too familiar today, including rising economic inequality, socialism, and a global pandemic.

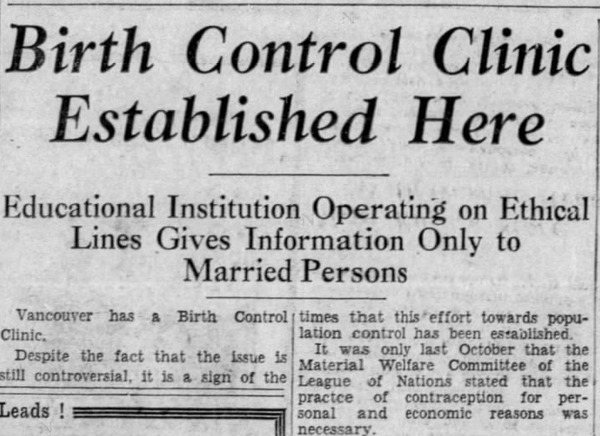

Clipping from the front page of the Vancouver Sun, June 17, 1932.

“The clinic is run along ethical lines,” noted the June 17, 1932, issue of the Vancouver Sun. “No abortives, or information concerning them is given out, contraception alone, is dealt with in consultations. The scientific use of contraceptives with emphasis on the medical approach of the subject of birth control is paramount … Individual local medical men have given their recommendation and advice to the clinic and several prominent women’s organizations have signified their interests in its endeavors.”

Run by nurse Laura Clements and social worker Frances Moren, the clinic (which opened just months after Canada’s first such clinic, in Hamilton, Ontario) provided more than $600 worth of free services in its first year before moving six floors up to Suite 1621 that fall.

But Moren was more than just a social worker; she was a well-known socialist, lecturer, and lover of physician and future mayor Lyle Telford. The pair had met while working together on the Challenge, a socialist newspaper founded by Telford, and as members of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (a democratic socialist party then just emerging in the Prairies, founded by Tommy Douglas, who would go on to lead the NDP).

Telford, a doctor by trade, had a commonsense approach to public health policy, having arrived in B.C. just a few years before the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic claimed the lives of nearly 1,000 Vancouverites.

And while access to birth control was never part of the CCF’s platform, most proponents of the movement in those early days were socialist—or at least hailing from the left side of the political spectrum. Railing against the “law and custom about birth control,” CCF co-founder J.S. Woodsworth told a Vancouver audience in 1919 that “in the new social order the prospective mother should be allowed to say whether she wished her child to be brought into the world or not.”

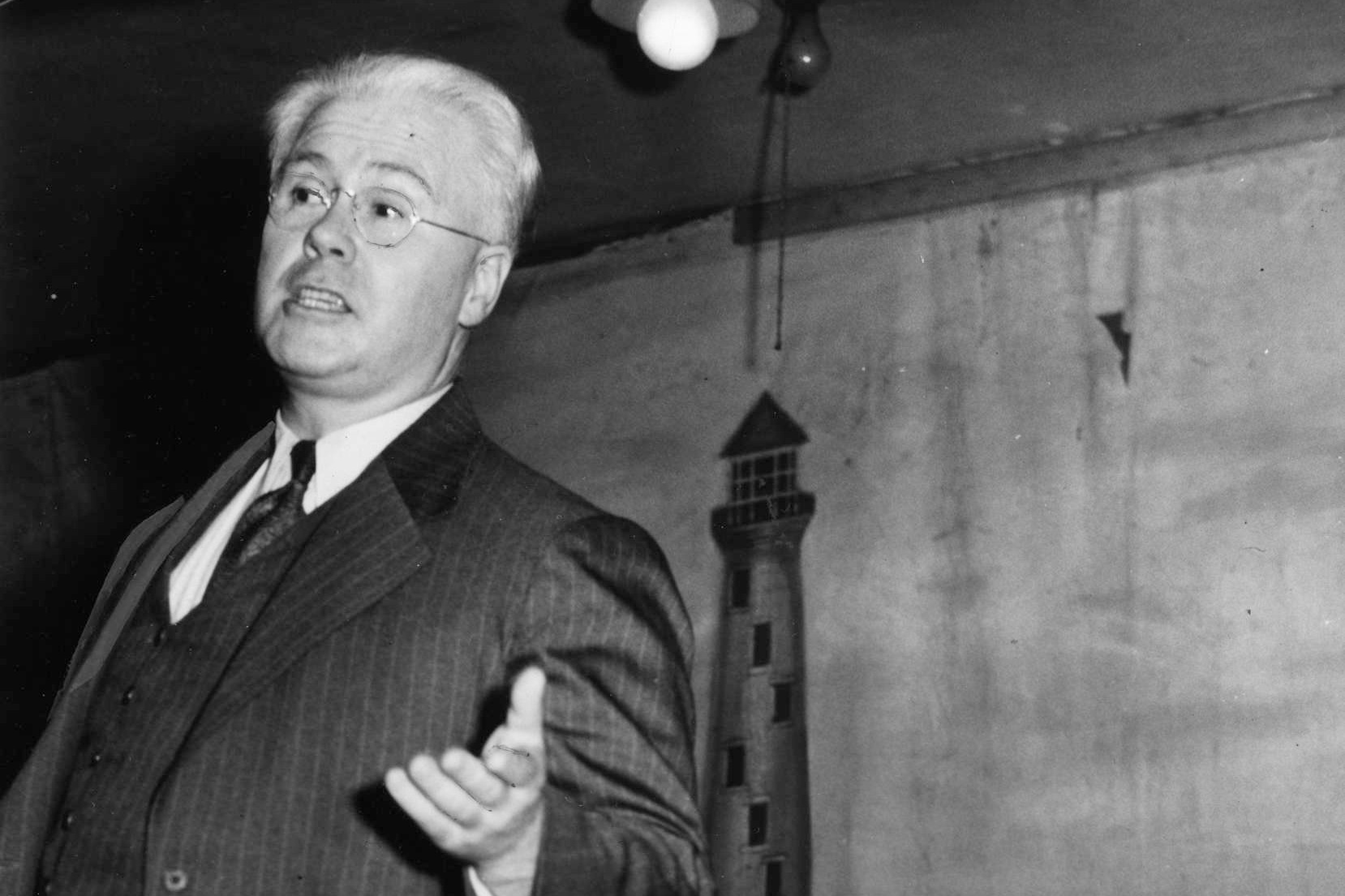

These ideas were slow to catch on. As early as 1928, Telford attracted considerable public ire after giving a lecture at UBC on “companionate marriage”—the idea that couples should practice birth control for the first two years, to reduce emotional distress in the event that the marriage failed.

“It is a reflection upon the good sense of the university authorities that they should allow a man to come into a university building and preach such degenerate rot as that,” complained the Vancouver Sun, in a March 15, 1928, editorial titled “Social Poison.” “Mental and moral discipline is of more value to the young people at the university just now than the liberty to make precarious excursions into the realm of freak sexual doctrines.”

Dr Lyle Telford giving a speech, circa 1930s. Image Courtesy of the Vancouver Archives.

Beyond providing a male figure to found the clinic (crucial, given the sexist politics of the day), Telford moved into the background shortly thereafter, providing referrals but otherwise leaving the day-to-day work to Moren and Clements. At first, its activities provoked a number of fire-and-brimstone-fuelled letters to the editor in local papers, but as the Depression deepened, attitudes around social services began to change.

In June 1932, just two months after the clinic opened, the Sun published a favourable article, noting that: “Despite the fact that the issue is still controversial, it is a sign of the times that this effort towards population control has been established.”

And less than a year later, publisher Bob Cromie threw his full support behind the idea, signing his name to an editorial stating that women were driven to “such extremes, not by criminal intent, but by ignorance of scientific methods and the stupidity of our laws … We lay down an unalterable law that women must bear children whether they want to or not. Then we shudder in pious horror when, in natural revolt and understandable desperation, they sneak off to some charlatan for an illegal operation.”

By 1933, Moren had left the clinic largely in the hands of Clements to pursue a political career as a CCF candidate in the anticipated provincial election. Telford and three other doctors continued referring patients, and Clements spent her days teaching women about contraception, fitting them with diaphragms, and travelling to smaller communities like Kamloops to espouse the merits of the birth control movement.

The Marine Building, 1929. Image Courtesy of the Vancouver Archives.

Curiously, despite operating in the open, the clinic never attracted the attention of police. As early as 1923, a Vancouver branch of the American Birth Control League had begun agitating for changes to the Criminal Code of Canada (which forbade contraception of any kind), without success.

“‘To encourage the poor, for supposedly moral reasons, to bring children into the world, when those children can only be victims of misery in times of peace and cannon fodder in times of war,” said early birth control advocate A. M. Stephen, in a July 1932 address, “is nothing short of criminal.”

The organization folded after two fruitless years, meaning that under the Criminal Code, providing contraception remained punishable by up to two years in prison. Luckily, the Vancouver Birth Control Clinic managed to operate in a legal grey area, thanks to an exception in the code that allowed leniency if “the public good was served by the acts alleged.”

Another reason that Moren may have taken a step away from the clinic was that, as of 1933, her own life was suddenly in the public eye: despite being married to another woman, Telford had carried on a relationship with Moren for almost 10 years. It didn’t matter that the marriage was loveless, or that Telford’s wife refused to grant a divorce, or that Moren was pregnant with Telford’s child. The CCF gave Moren an ultimatum: leave Telford, or step down as a candidate. She chose Telford, and carried the baby to term.

Cooperative Commonwealth Federation poster, circa 1930s.

The scandal didn’t damage Telford’s reputation, or the CCF’s; in the 1935 B.C. election, riding on a wave of socialist sentiment propelled by the Depression, the party became the official opposition in the provincial legislature. Telford himself became Vancouver’s mayor in 1939. The CCF’s rise would be short-lived; alarmed, B.C.’s wealthy business interests had already begun a concerted campaign to retake control of the province (a campaign that led to, among other things, the formation and decades-long civic dominance of the NPA).

In the meantime, the Vancouver Birth Control Clinic remained open, changing locations several times—including briefly, into the home of Laura Clements (who by then had married and adopted the last name Vaughan). The clinic operated until 1955, when Clements’ husband died. Then, in the ultimate act of patient protection, she destroyed all 23 years’ worth of records and moved to California. While Frances Moren lived until 1973, Telford only outlived the clinic he helped launch by five years (although his third wife claimed she spoke regularly with his ghost).

After its closure, the hole left by the clinic was filled by nurse Vivian Dowding, who had started a practice of her own in the Interior, but regularly visited Vancouver to provide sexual health services. Despite being employed by the Ontario-based Parents’ Information Bureau, she was harassed on several occasions by small-town bureaucrats, including one in Mission, B.C., who called the police.

In addition to being a nurse, Dowding was also a socialist advocate, whose passion for sexual education stemmed from her mother’s childhood advice to avoid pregnancy through douching (a practice which led her to give birth to three children in as many years).

In 1969 the Criminal Code of Canada was finally amended to legalize contraception. And today, following in the footsteps of Moren and Clements, organizations such as WISH are actively working to provide sexual health services to low-income and disadvantaged women and sex workers—an approach supported by today’s public health officials.

Just this week, B.C.’s provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry partnered with Melissa Caron, the jeweller who made the gold bee that often hangs around her neck during press briefings, to produce a line of jewelled bees, the proceeds of which will support WISH. The bees symbolize Henry’s familiar motto, to “be kind, be calm, and be safe,” as well as a partnership of science-based public health decision-making and concern for women’s sexual health that follows the tradition of the first Vancouver birth control clinic.

Jeweller Melissa Caron’s “Bonnie Bee” pendants. Image courtesy of Melissa Caron.

Unlike some politicians to the south, who are using the current economic downturn and pandemic panic to strip away women’s reproductive rights, B.C.’s top doctors and policymakers have, for almost a century, taken their cue from experts—experts like Lyle Telford, Laura Clements, and Frances Moren.

“[W]e see no reason why they [wealthy women] should have a monopoly of that privilege,” Telford once argued, in the pages of the Challenge. “Women rebel against larger families than they can feed and clothe. Many of them resort to desperate measures, and not a few endanger their lives.”

“Unfortunately, far too great a burden falls upon voluntary efforts in regard to birth control for poor people,” Moren added in a May 1935 editorial in the Vancouver Sun. “Only when the general public and officialdom are prepared to take the stand that parenthood is too important to be left to chance, and that, in all circumstances, motherhood should be entirely voluntary, can childhood be assured its first great right.”

Read more stories of historic Vancouver.