Doug Hudlin was feeling every one of his 88 years on a crisp February day in Victoria 10 years ago. The Gentleman Umpire, as he was known, had left a sickbed to introduce to a small public meeting the great Ferguson Jenkins, the retired baseball pitcher who was the first Canadian to be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

Afterward, Jenkins, the descendant on his mother’s side of escaped slaves who found freedom in Canada after travelling the Underground Railroad, spoke privately of his experiences as a young player under Jim Crow segregation in the southern United States in the 1960s. He was barred from hotels and restaurants, from the sandy shores of Miami Beach, and some even wanted him banned from the baseball diamond.

At age 20, the lanky, right-handed pitcher from Ontario arrived in Little Rock to pitch for the Arkansas Travelers. “At the airport,” Jenkins told me, “there were a couple of banners that said, ‘We don’t want black players.’” He paused, then confessed the banners actually used a racial slur.

Jenkins’ stories reminded the old umpire of his own family’s past. His father, a shoeshine man, worked in the basement of a hotel whose lobby he was forbidden to cross. Hudlin, who was the first non-American and perhaps the first Black man to umpire a Little League World Series game in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, spent years labouring over a family tree, compiling more than 400 names. His great-grandparents were Nancy and Charles Alexander, both free-born Blacks from the United States who fled discrimination in California to settle on a farm on the Saanich peninsula just north of Victoria.

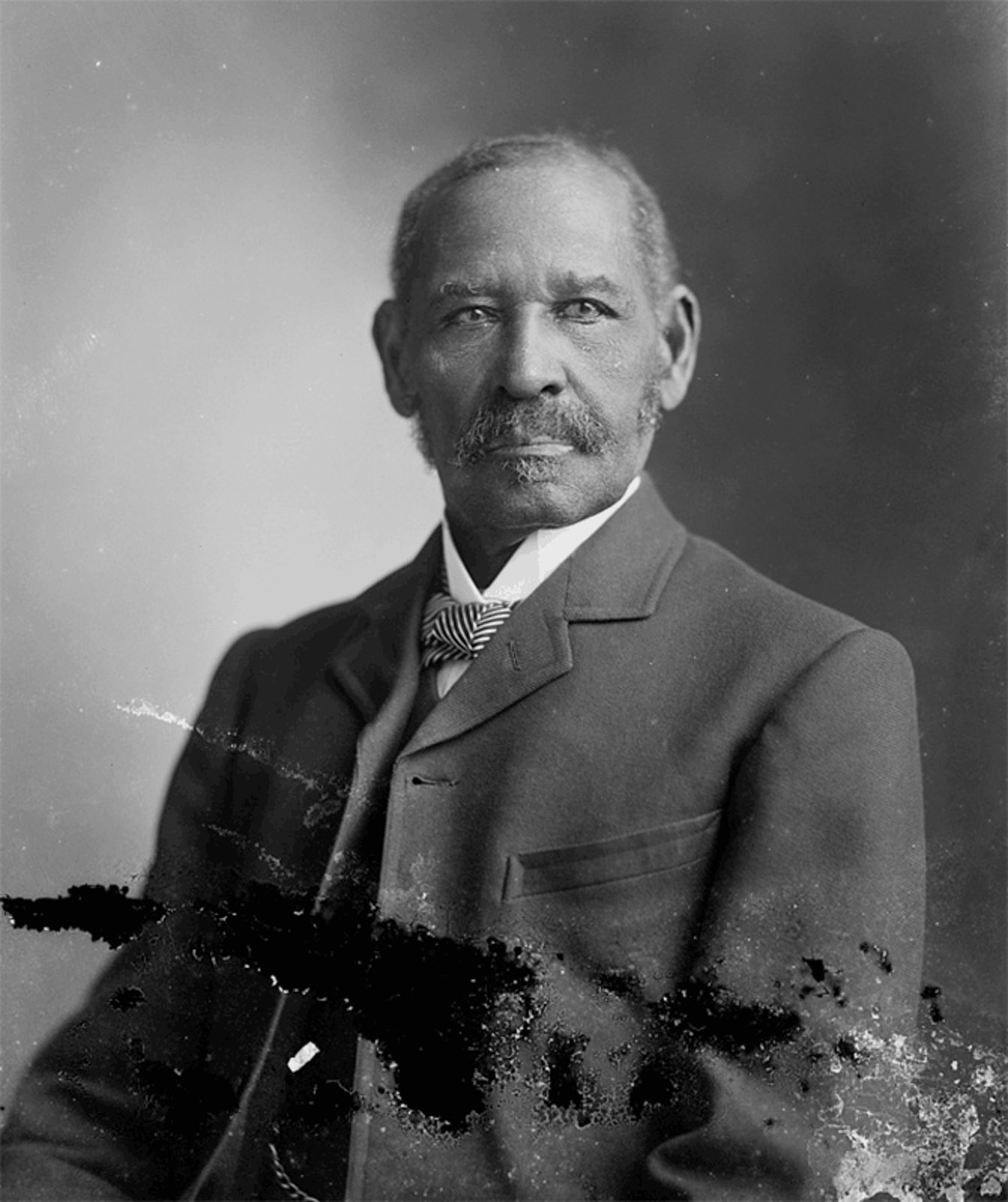

A studio portrait of Nancy and Charles Alexander on their 60th wedding anniversary. Image courtesy of Royal BC Museum and Archives, A-01068.

As news of a gold strike on the Fraser River reached California, fortune seekers clamoured to go north to seek their fortune in British territory. On April 25, 1858, five days after sailing out of San Francisco, the steamer Commodore docked in the Inner Harbour of the capital of the colony of Vancouver Island. The arrival was a raucous affair, as several men among the 450 passengers waved pistols and made a commotion in the city, though their free spending in stores and taverns soon made them less of an annoyance. Soon, some 400 of them headed off to the gold fields on the Fraser River.

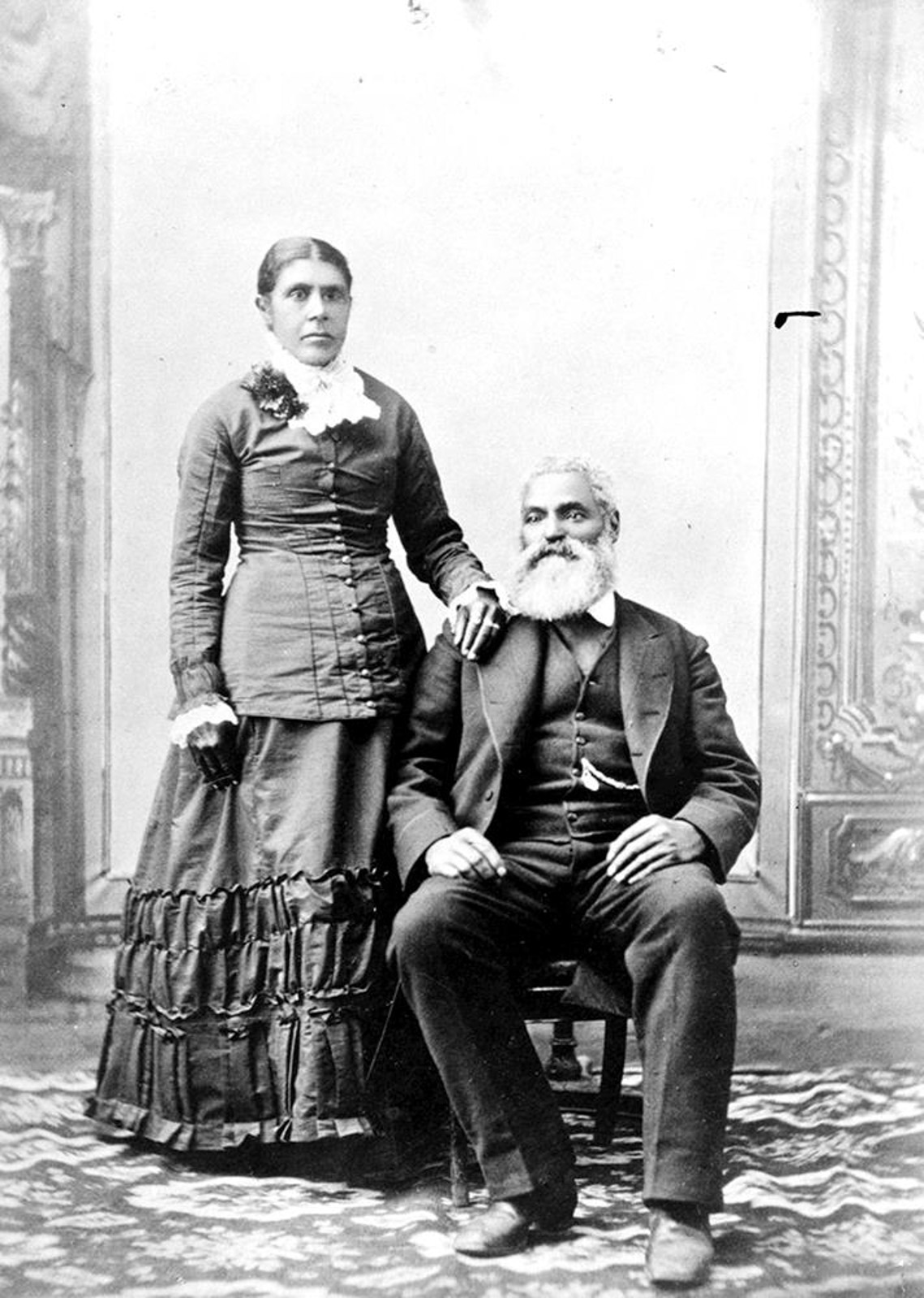

More than 30 of the remaining passengers were an advance party of free Black Americans who were escaping increased racial discrimination and the constant threat of being harassed or seized under the Fugitive Slave Act passed eight years earlier. The British colony’s governor, James Douglas, himself of mixed European and African ancestry, was encouraging free Blacks to emigrate north. He was seeking permanent settlers who might prove loyal to the British, unlike the wild and unpredictable armed Americans flocking to the gold fields. He promised that after seven years, landowners who swore allegiance to the Crown would have full civil rights.

Governor James Douglas was of European and African ancestry. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

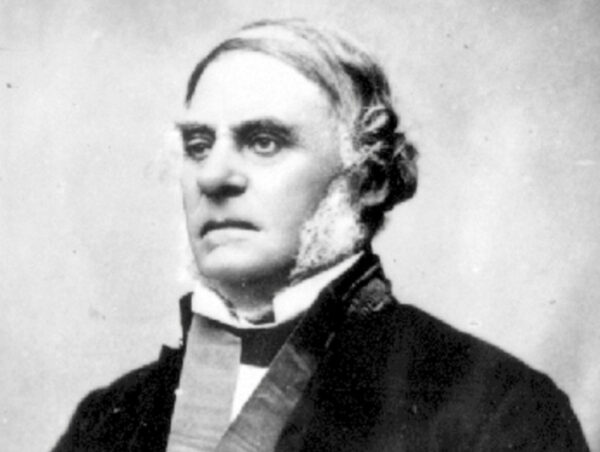

That summer, the first wave of free Blacks arrived to plant farms and open businesses. The Alexanders, the umpire’s great-grandparents, arrived aboard the Oregon. “Three or four hundred coloured men from California and other states, with their families, settled in Victoria, drawn thither by the two-fold inducement—gold discovery and the assurance of enjoying the benefits of constitutional liberty,” the remarkable Mifflin Wistar Gibbs wrote in a memoir. He arrived in June, wisely bringing with him bacon, blankets, flour, and such tools as picks and axes for miners. A carpenter by trade, he opened a dry-goods business with long-time business partner Peter Lester, a bootmaker. The easiest money to be made in gold mining was not to be found in the gold fields but in supplying gold miners, and Lester & Gibbs thrived at a shop on Yates Street just two doors from busy Waddington Alley.

In later decades, Victoria would be promoted as a garden city more British than the British, but in those early gold rush years the capital was more Deadwood than Downton Abbey.

Gibbs prospered, developing several properties, including a grand building on the east side of Government Street north of Fort Street with large display windows and an interior featuring polished mahogany counters and chandeliers overhead, which later became the first of the chain of department stores owned by David Spencer.

Just two years after arriving, Gibbs and 17 other Black men voted for delegates to the House of Assembly, swinging the election to a slate backed by Governor Douglas, rather than one promoted by reformer Amor de Cosmos, publisher of the British Colonist and, later, premier. Gibbs and de Cosmos would later work together to bring the united colony of British Columbia into Confederation, the sesquicentennial of which will be celebrated later this year.

After several tries for office, Gibbs was elected to Victoria city council in 1866 as representative of his home ward of James Bay, serving as the first elected Black official in B.C.

An advertisement in the British Colonist for Lester & Gibbs store, January 21, 1860.

Not everyone was welcoming. Some locals objected to the presence of Black patrons at the Victoria Theatre. An amateur concert in 1861 was interrupted when a paper bag of white flour was thrown at some Black patrons in the audience. The bag burst on the head of Nathan Pointer, a clothing importer, covering him and his wife in white dust. Gibbs and his wife were nearby.

“The outraged men rose from their seats,” the Colonist would recount many years later, “and were with difficulty kept from wreaking swift vengeance on a party of Northern Americans who stood in a row in the rear of the dress-circle and who were more than suspected of throwing the flour.” After a scuffle, the show resumed.

A more shocking event had occurred the previous year. James Tilton, whose reward for supporting Franklin Pierce for the presidency was a patronage job as surveyor-general of Washington Territory, had brought a slave with him to the Pacific Coast. Some Black residents of Victoria saw the 13-year-old boy with the white family in Olympia and encouraged him to escape to Vancouver Island, where he would be supported by the local Black community.

On September 24, 1860, Charlie Mitchell snuck aboard the mail steamer Eliza Anderson. The cook, James Allen, hid him in the galley. When the captain discovered the stowaway’s presence, he locked him in the ship’s lamp room, refusing to let him out even after docking in Victoria, intending to return him to his owner as property.

More than 100 Black and white Victoria residents gathered in front of the ship in the Inner Harbour. A lawyer was hired, and the sheriff, armed with a writ of habeas corpus, forced the captain to surrender his prisoner. The boy spent the night in a Victoria jail before being released and given his freedom the next day by Chief Justice David Cameron (who was, incidentally, Douglas’ brother-in-law). Slavery had been extinguished throughout the British Empire so the court would not recognize the American’s claim of ownership.

Mitchell’s later life is uncertain. It is possible he returned to his native land after the Civil War, however a Charles Mitchell is listed in residence at the Augel Hotel in Victoria in 1874. Sadly, a Black man named Charles Mitchell and a white man known only as Bill drowned two years later when their canoe loaded with shingles in Sooke was later found washed up on the shore. That Mitchell left a wife and four children, one of them a newborn.

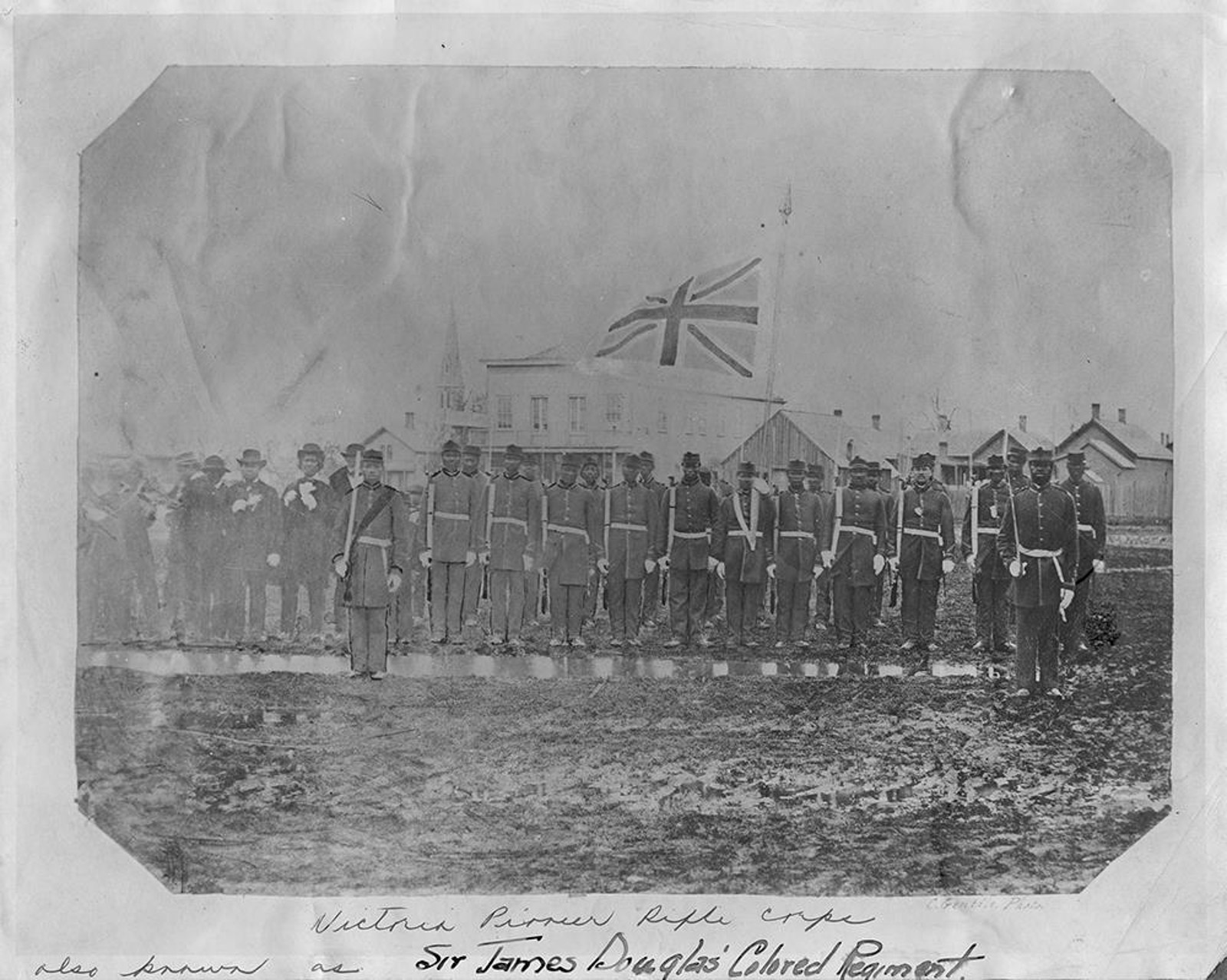

The boom in the city’s population also led to the formation of volunteer fire brigades. When white firefighters refused to allow Blacks to join, the new Black arrivals instead formed the Victoria Pioneer Rifle Corps, also known as the Africa Rifles. Some 50 men belonged to the outfit, drilling and parading through town.

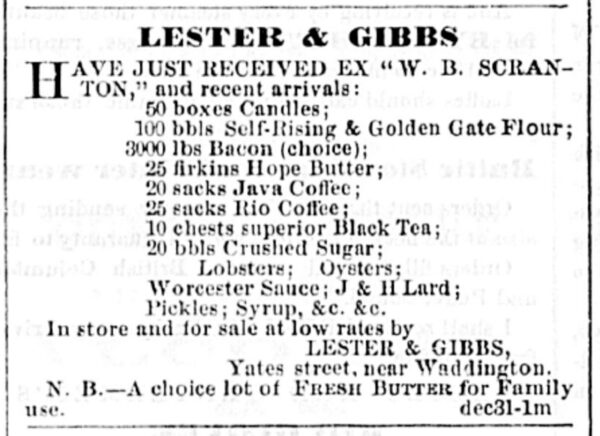

The all-Black Victoria Pioneer Rifle Corps. Image courtesy of Royal BC Museum and Archives, F-00641.

As the first militia in the province, they marched along the waterfront. Though armed only with antique flintlocks, their presence was to be a lesson to the arriving American fortune hunters. The Blacks in this British colony were not only free men but armed and carrying the imprimatur of the state.

The militia members were nevertheless barred from a farewell banquet for Governor Douglas and were also kept from taking part in the welcoming parade for his replacement, as the all-white volunteer fire brigades refused to march behind them in the procession.

In 1865, the militia disbanded and the white establishment began enforcing various discriminatory practices. With the Civil War ended, some of the early Black settlers, including Gibbs, drifted back to the United States. Gibbs became a judge in Arkansas before being appointed U.S. consul in Madagascar.

The earliest Black immigrants sought to reassure the residents of their desire to form a permanent settlement, finding in the British colony at least for the first few years the very promises denied them in their homeland.

“We have come to this country to make it the land of our adoption for ourselves and for our children,” Reverend J.J. Moore wrote in an early edition of the British Colonist in 1859. “We have come to possess the soil; to till the earth; to reap its productions; extract its minerals; to mould its rocks and forests into firesides; and to fill the solitary places with joy and gladness; to gild the western verge of old ocean with white winged messengers to glide upon the bosom of every sea; and build up for ourselves and children, happy homes in the land of the free and the home of the brave.”

Black History Month is being celebrated in British Columbia in February with numerous virtual events in the Lower Mainland and Victoria, including lectures, a symposium, musical celebrations, and an online tour of gravesites of Black pioneers. (Some require registration in advance.) Read more Community stories.