Sam Greer was surrounded.

Gun drawn, the Vancouver pioneer and former Union soldier leaned against the back door of his beachfront shack, and waited.

“Open this door, Greer,” a voice shouted.

It belonged to Deputy Sheriff Tom Armstrong of the New Westminster police. It was early morning in September of 1891 and, moments earlier, Armstrong had arrived with a posse—three provincial police and a group of heavies hired by the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). Their goal, after seven years of legal wrangling, was to serve Greer and his family with a Writ of Eviction that would displace them from their own land.

Greer had other plans.

“Get away from there,” he retorted, “or things are going to get hot for you.”

He had seen them coming. The front door was barred, his wife Louisa and their daughters safely inside the cabin—their home for almost a decade. Outside, accompanying the posse, was Francis Carter-Cotton, owner of the Vancouver Daily World, who would later catalogue the incident in painstaking detail.

“Open the door,” Armstrong repeated.

Greer said nothing. Instead, he shoved the muzzle of his rifle through the back door, and started firing.

“Some half-dozen of the bullets struck and entered Mr. Armstrong’s left cheek,” Carter-Cotton wrote, “one also going through his clothes and burying itself in his chest over his heart.”

Shocked, the police and railroad heavies retreated. But it wasn’t long before they would return in force. And the incident would prove to be the climactic chapter in the struggle between a handful of families, and the largest corporation in the country—a struggle that would ultimately lead to the creation of what’s known today as Kitsilano Beach.

Sam Greer. City of Vancouver Archives.

For more than 130 years, real estate has been Vancouver’s biggest industry, and during much of the 20th century, there was no bigger player in the property development game than the CPR. As it moved west across Canada, the railroad held immense power to make or break communities, and used this influence to demand large swaths of free land from both the Crown and private landowners. The land grant around Burrard Inlet was the largest in the country, including much of the land in modern-day Coal Harbour, and on the downtown side of False Creek. Sales of that land would eventually reap the company more money than every other company town in Canada combined—to say nothing of the vast wealth gained by its executives and their friends, who used inside information for speculative gain.

During the late 1880s, the railroad had shaped virtually every aspect of civic growth, from the location of the downtown core (centered around their property on modern-day Granville Street), to the creation of Stanley Park (unable to secure the federal land for sale, they petitioned Ottawa to turn it into a park, thus securing themselves against dropping property values), to the name of the city itself (President W.C. Van Horne decided on “Vancouver”, in spite of local and provincial opposition). In addition to their holdings in the West End and around Coal Harbour, the CPR worked feverishly to acquire as much waterfront property along the south side of False Creek as possible—land that included the Greer’s, and their immediate neighbours to the west: the Squamish village of Snauq. The ancestral home of the Khatsahlano family, Snauq had been designated as “Indian Reserve No. 6” during the Royal Engineer’s Survey of 1869, and by 1877, had been expanded from its initial 37 acres to 80. This presented a problem for the railway. Provisions of the Indian Act and Railway Act mandated that any reserve lands appropriated by the CPR would require consultation with and compensation for the communities living there.

And the Khatsahlanos weren’t just any family.

Within the hierarchy of the Coast Salish, they were about as high-ranking as they came, with a home at Snauq, and another at Chaythoos (in modern-day Stanley Park). Their family’s habitation of the area went back at least three generations (although archaeological evidence of First Nations activity goes back thousands of years before that), and August Jack Khatsalano—then only a boy—would go on to succeed his father as the head of the Squamish nation. That said, they had already been displaced from one ancestral home, when the CPR’s machinations led to the creation of Stanley Park and the removal of the families who lived there. To add insult to injury, the body of August Jack’s father, buried in an above-ground mausoleum near their home, was moved to Squamish, and a midden—containing the remains of generations of ancestors— was used to pave the road.

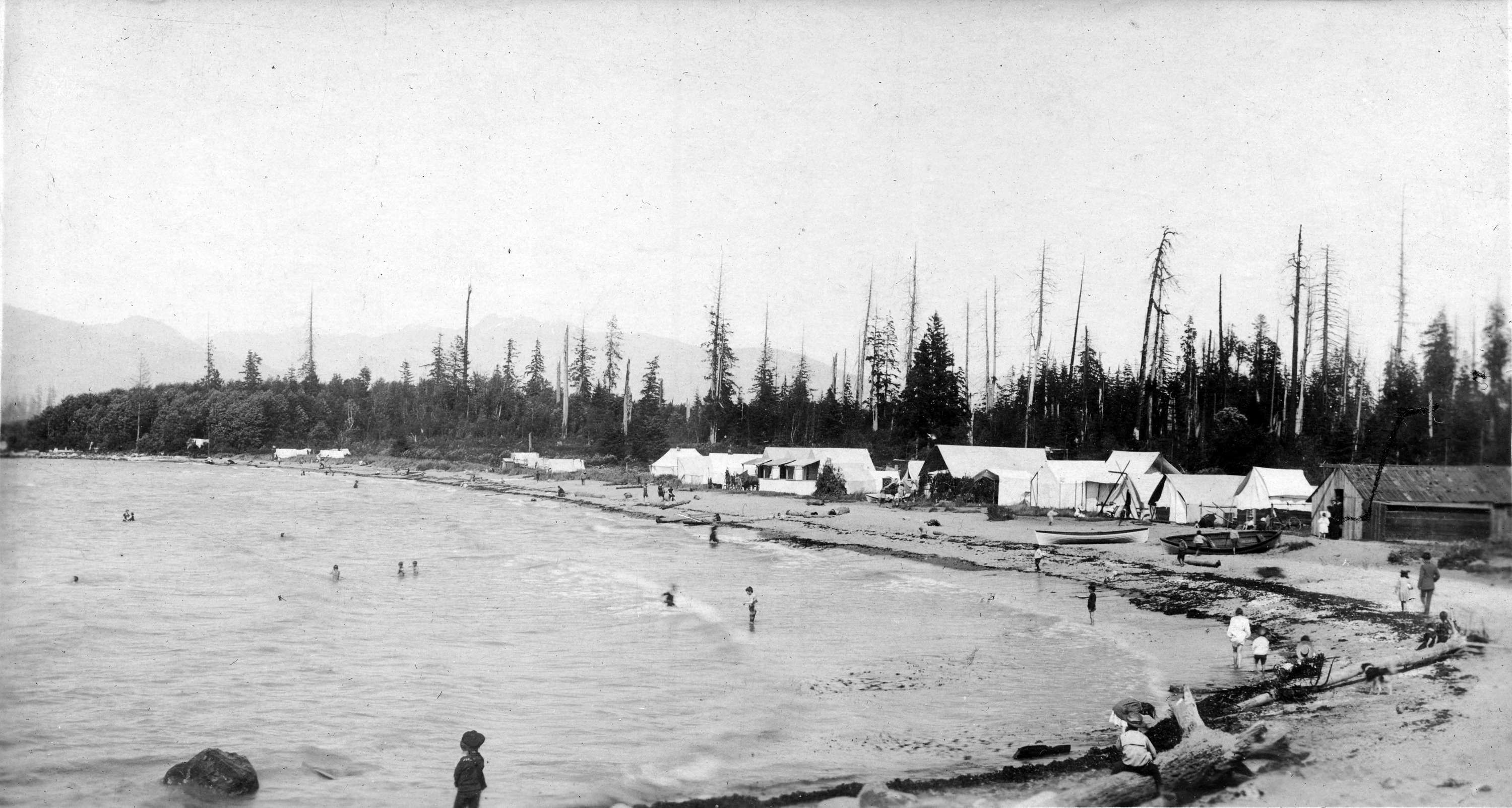

Kits Beach, 1914. City of Vancouver Archives.

While not as impressive as the inhabitants of Snauq, the Greer family’s habitation of the area nonetheless went back more than a decade. Having purchased nearly 200 acres of prime beachfront property on Burrard Inlet back in 1884, Sam and his wife went on to build a quaint homestead for their growing family. Unfortunately, given the land’s immense value for development, the Greers quickly ran afoul of the CPR. Already, the railroad had spent the better part of a decade attempting to get its hands on the land (which it had earmarked as a beach resort), in a fight that was then making its way to the Supreme Court. Initially, the railroad had tried gentler tactics: Van Horne first enlisted local speculator Gideon Robertson to make an offer on the property, but Greer —known for his pronounced stubborn streak—indignantly refused. Undeterred, the company began working to undermine the legitimacy of his claim, taking him to court with allegations that the original land title paperwork was forged. This too proved unsuccessful. But while fighting the matter in the courts, the CPR began treating the land as if it were already theirs, erecting telegraph lines along the property, and having a Writ of Eviction drawn up. Despite these efforts, public opinion—including that of major newspapers like the World, was largely on Greer’s side.

“They say the CPR wanted title to the land but the government was afraid to give it to them, fearing some after action,” explained city pioneer H.P. McCraney, “but [the government] said to the CPR that, if they could get Sam out of the way, or at least if the CPR would guarantee quiet possession for ten years, they would give the company the title.”

But Greer had no intention of staying quiet. And by 1891, the CPR was growing impatient. Armstrong and a crew of deputies had already been dispatched earlier in the year, crowbars and axes in hand, with orders to remove the family from their property.

“When we got there Sam was not at home,” explained deputy Arthur Langley, in an interview with city archivist JS Matthews, “but his wife was, and she objected strenuously; raising trouble. Finally, under the direction of the Sheriff, Charleson and his men took off the door, and commenced carrying the furniture outside. Well. Then Sam came along; evidently he was out around some place, and he also started to interfere with the Sheriff’s orders, stopping the men, and the Sheriff put him under arrest.”

For a moment, Greer seemed to capitulate. He insisted he would come quietly, and stepped inside to change his clothes. A moment later, he emerged brandishing an axe. And while Greer wasn’t prosecuted for that incident, his fortunes were about to change. Two days after the shootout with Armstrong, a second delegation of police descended on the property and arrested him on charges of attempted murder. Within the hour, as Greer languished in a cell, and before ownership had even been decided in the courts, deputies began removing the furniture and his family from the property.

“You may shoot me if you like,” Greer’s wife said, as reported in the Sept 22nd, 1891 issue of the World. “You may as well kill me as take the best of me away, and then want to turn me out during his absence.”

But it was no good.

“The gang of men then started to work,” Francis Carter-Cotton wrote, “taking the furniture out of the house and loading it on to a box-car, amidst the loud scream of one of the little girls.”

“Sam made one terrible mistake,” Captain J. Hampton Bole later said, to J.S. Matthews. “If he had not fired that gun at Tom Armstrong, he would have held his property. That mistake cost him the possession of part of our city. Public opinion was so strong that the CPR would have had to have given in; the people would have torn up the rails as fast as they laid them.”

“Well,” Louisa Greer said, as she watched crews dismantle her home. “I’ve gone through a good deal in my life, but this beats everything I ever saw.”

Kits Beach 1900. City of Vancouver Archives.

Within the hour, those same crews would have to bodily remove her from the property. Sam Greer went on to spend 30 years petitioning the government for compensation, to no avail.

The inhabitants of Snauq suffered a similar fate.

In order to avoid consultation with the Squamish community, and to more quickly secure rights to their land, the CPR employed a system of legal tricks that had served them in good stead elsewhere in the country: they argued in court that Reserve lands were private property—a much simpler process, which only demanded a certificate from the Minister of Railways, and thus allowed them to leave the communities out of the process altogether. Then they set a route for a right-of-way, did their own independent valuation of the land, and offered the residents a pittance to move. To that end, they submitted a woefully underdeveloped plan to the government in the spring of 1886, claiming the region was of vital importance to their operation (in a private letter, Van Horne admitted that they had no immediate plans for the land, and would figure it out once they had removed the First Nations). So certain were they of success, they began laying tracks and posting notices before the matter had even been decided.

But during the valuation process, they hit a snag: ordinarily, government employees didn’t bother to verify the CPR’s figures (often ridiculously far below market value), choosing instead to take the company at their word. However, when Indian Affairs Superintendent Israel Wood Powell visited the region, he derided the company’s valuation as an “absurdly small nominal sum”(the CPR’s valuation priced the land at $55.60 per acre, when in fact it was worth more than $1800). The railway did manage to acquire certain portions of the Reserve—the first in 1886, and the second in 1901—but ultimately, the remaining land near Snauq was purchased by the provincial government. And neither they, nor the city, was interested in playing landlord.

In May of 1901, the city requested “the removal of the Indians from the reservation on the south side of the mouth of False Creek, just around from Greer’s Beach,” reported the Vancouver World. “Mayor Townley has communicated with Frank Devlin, Indian Agent, in regard to the matter, pointing out that the place was no use to the Indians themselves, that it had become nothing more than a place of carousal, and other than being a source of menace to the morals and health of the City and the Indians, was a distinct source of trouble to the nearby municipalities.”

Kits Beach 1889. City of Vancouver Archives.

The residents of Snauq weren’t ultimately displaced from their land until 1913, when the BC government paid out $225,000 to 20 members of the community ($11,000 each) for property worth an estimated $7-million. The men who closed the deal, Hamilton Reid and H.O. Alexander, were paid a total of $80,000 for their services. The city and the CPR had their beach. But despite the removal of its most famous (white) resident, it remained known as Greer’s Beach for 10 years after his departure—until the railway asked for the help of Vancouver pioneer, and government employee/railroad insider Jonathan Miller to help in removing all trace of its former adversary.

“Kitsilano is the new and official title for the locality hitherto known by the old-time name of Greer’s Beach,” wrote the Province, in July of 1901. “Kitsilano was a famous Indian chief 30 years ago, who was the only man who could hold down the Euclataws and other warlike tribes of the north […] He was chief over all the small chiefs between here and Texada, and had command of the entire Squamish Indians in their fights. The word Kitsilano itself means grand, magnificent and great.”

In fact, the word “Kitsilano” didn’t mean anything. Miller had—accidentally or otherwise—anglicized the name of the Khatsahlano family. The same Khatsalano family that the railroad had now twice displaced.

“I think Sam Greer had what we call a ‘raw’ deal,” said H.P. McCraney, in an interview with J.S. Matthews. “He was the only man in Canada who ‘held up’ the CPR, but they were too strong for him. Alex Henderson told me that he was at the trial, and that Judge Begbie bulldozed the jury into finding Sam guilty, and gave him eighteen months in gaol. Henderson said he never saw a worse case of a judge bulldozing a jury.”

This story from our archives was originally published on July 26, 2019. Learn more about local history in our Hidden Vancouver series.