I gaze down at the shoreline fringe of the Sunshine Coast, where the long fingers of the Sechelt, Salmon, and Narrows inlets splay out from the Strait of Georgia. Below the airplane, the Agamemnon Channel meets the Skookumchuck Narrows. Lois Lake is a placid arc to the north. Nelson and Texada islands come into view, viridescent.

I’m on the Talaysay Land, Sea & Air Audio Tour, listening to Candace Campo’s voice. Her soft lilt is hypnotic. I hear stl’íxwim (Narrows Inlet), skúpa (Salmon Inlet), lékw’émin (Jervis Inlet), sxwélap (Thormanby Island), and I feel like I’m flying, not only over the here-and-now but also back through time to when this world was created. Local legends, sea creatures, and wildlife come alive through Campo, a member of the shíshálh (Sechelt) Nation.

Launched in 2023 with Sunshine Coast Air, the hour-long flightseeing tour is enriched by the cultural-historical perspective and narration of an Indigenous person. Campo, whose ancestral name xets’emits’a translates to “to always be there,” knows the topography like the palm of her hand. She was born here, at the head of Porpoise Bay. “I felt like the most fortunate kid in the world,” she says, “because I spent every day of the summer with my father, and we fished all summer.” They fished—herring in the spring, salmon in the late summer—in Sechelt Inlet, where the plane takes off, and dug for cockles and clams at low tide. “It was a good life.”

Aerial view up Salmon Inlet from Sechelt Inlet.

She founded Talaysay Tours in 2002 and is known for her inspiring Talking Trees tour, which introduces visitors to Indigenous knowledge and connection to nature. Campo started her career as a kayaking guide—and still loves getting out on the water whenever she can—but her goal is to educate, train, and support the next generation, sharing her expertise in the business of tourism while also revitalizing and reclaiming Indigenous culture.

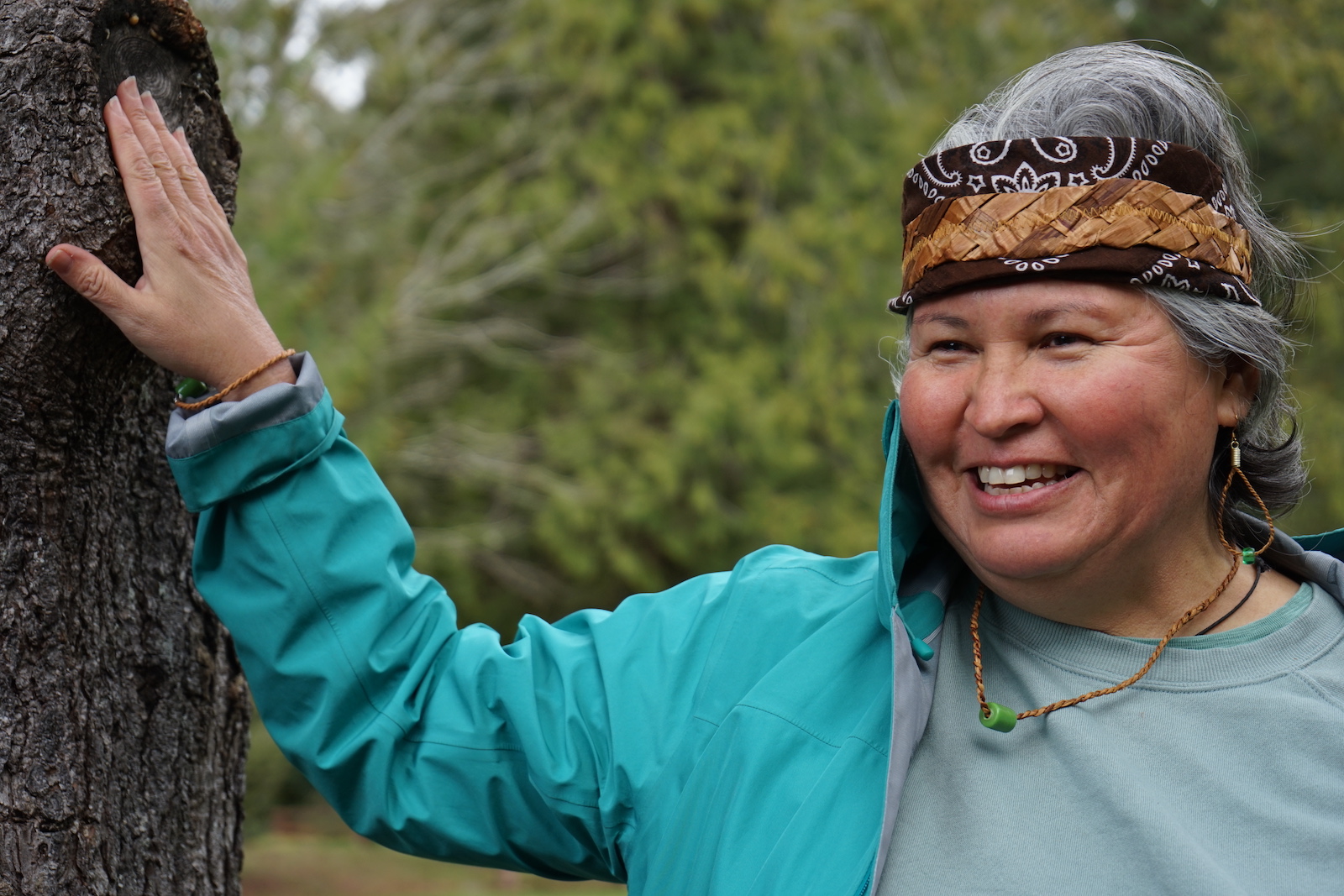

Candace Campo in the floatplane.

Beyond the flightseeing tour, she’s developed an app that lets anybody access her tours from a smartphone. Generations of oral history and teachings are shared using a location-based video player and interactive map, allowing anyone, anytime, to explore the Talking Trees and Talking Totems tours. It’s revelatory to hear Campo’s take on the land, history, art, and culture while walking with her where her ancestors have lived for thousands of years.

After leaving the floatplane, Campo takes me on a walking tour in Porpoise Bay Provincial Park, showing me the land from the ground now instead of from the air. Her close friend and colleague, Richard Till, joins us. The Elders have given him the name smanit stumish—Mountain Man—and he has guided with Campo for more than 27 years. He’s not Indigenous, but Campo’s aunt took him under her wing and shared the stories of the places where he canoed and hiked on the Sunshine Coast.

Flying over Skookumchuck Narrows.

Today, Till works with Campo to pass on that knowledge to young people, training them as guides and cultural ambassadors for Talaysay Tours. Till says, “The Elders fuelled, inspired, and actuated all the programming we did over the years. Plant-use technologies, ethnobotany, ethnoecology all came from the Elders, who went up and down the coast and gathered the info.”

But it goes beyond that. “It’s more than land-based learning,” says Till, “because what we’re doing is reconnecting people to land and culture through the stories of each family.” He speaks plainly about learning to “decolonize his mind and heart” and look at things differently from how he was raised, in an extractive society based on commodity and subjugation.

Candace Campo in front of a towering western red cedar, the tree of life.

“As Indigenous people, we truly believe we are one—and it’s not just about Indigenous people having a relationship to the land but all of us having that relationship to the land,” says Campo. Her tours show how Indigenous people use the land for food, medicine, technology—and now tourism. “Participating in tourism as an Indigenous person is really about being a part of your community and supporting your community.”

In the fragrant forest, with the soundtrack of the wind blowing and the waves lapping at the shore, Campo and Till tag-team the tour. He points out the bent branches of a tree with the apt Latin name Pinus contorta and says, “What makes the shore pine important, other than its intrinsic value as a beautiful living plant that enriches the environment, is its traditional uses.” Campo explains that the sap is a natural antiseptic and disinfectant, the “most healthy Pine-Sol.” Till adds that the sap was used as caulking and glue, and even chewed as a mouth-freshener. “It’s yummy,” says Campo.

The two of them open up a whole new world. I learn that Oregon grape roots are used to treat intestinal ailments (Till uses them to alleviate his Crohn’s disease), fir resin is ideal for lighting fires, spruce sap is used to aid fertility, and the longer needles on Ponderosa pine are woven to make baskets. “This is an area of plentitude,” says Campo of the forest and sea gardens. Here, her people use 150 types of trees and plants for food and medicine, and they have access to more than 500 sources of nourishment in the ocean. “When the tide is out, the table is set.”

Candace Campo with Josh Ramsay, owner and pilot at Sunshine Coast Air.

As we walk in tsúlích (Porpoise Bay), Till says, “We don’t speak of this as a village that used to be here, because in the hearts and minds of people this is still the village—it’s here.” He points out a shell midden three or four feet deep that has accumulated gradually over hundreds of generations. And I picture this swath of land as I saw it from above, while I swooped over Sechelt Inlet in the floatplane and listened to Campo narrate the shíshálh creation story.

Campo also told the story of the spipiyus, the shíshálh name for the marbled murrelet that lives in the coastal forests of the Caren Range on the west side of Sechelt Inlet. The whimsical ocean bird nests only in moss on old-growth trees. In an ecologically symbiotic relationship, the bird’s feces and the remnants of its seafood meals are a nutrient-dense fertilizer that nourishes the ancient forest floor. Part of the bird’s home is now protected in Spipiyus Provincial Park, where dome-shaped Mount Hallowell looms. From the plane, I am able to glimpse this landmark as the spipiyus does.

Whether soaring like spipiyus in the floatplane or stopping to touch the bark of a cedar while walking Sechelt Inlet’s shores, I feel the connection to nature that Campo and Till both nurture. “Our people have a reverence for the land,” says Campo. “When we talk about the land, we talk about everything—the ocean, the trees, the animals—but we also include ourselves.” Humans are part of nature, but we need reminding. Through her tours, Campo immerses people in history, culture, and the land itself. It’s all here. As Campo says, “It’s recorded in the land. The land is the witness.”

Read more stories about community.