It was the dog days of summer, 1926, and in the British Columbia lumber town of Cranbrook, talk was mostly of the upcoming federal election. As darkness fell on August 6, CPR dispatcher J. Francis Guimont tapped out an alarming warning by telegraph: “All trains west. Cranbrook. Keep look out for elephants on track. Advise if sighted from first telegraph office giving location.” Six elephants were loose in the Canadian wilderness.

This was big news. It made the front page of newspapers across North America. Reporters at the local Herald and Courier sent out a torrent of bulletins throughout the night and into the following week. As darkness fell, elephant sightings were reported from as far away as Yahk, an improbable 40 miles down the line. In reality, the pachyderms had vanished.

Local reports from the time are limited—the next issue of the weekly Cranbrook Herald wasn’t published until six days later—but here’s what we can piece together. That morning, 14 elephants were being unloaded from a Sells-Floto Circus train in preparation for the show in the afternoon. The circus, with over 1,000 crew and performers, including dancers, trapeze artists, clowns, and a Wild West show, had already had trouble with the elephants in Edmonton a few days earlier, when some of the animals broke away at the rail yard and stampeded down Jasper Avenue, rifle-slinging circus men in tow. The following day saw a second soon-foiled escape attempt in Calgary. The circus minimized the events and carried on with its tour uneventfully through Lethbridge and Blairmore.

Then, as the elephants were unloaded on a siding near a Cranbrook lumber office, spooked by barking dogs and honking car horns, they stampeded—trunks high and ears flapping—and headed for the mountainous wilderness surrounding Cranbrook. Six of them made it, crossing the tracks, traversing the cemetery, and plowing through the dense bush in the general direction of (the since renamed) Jap Lake. The rest were quickly rounded up after dead-ending in a nearby lumber yard. The fugitives included Tilly, Myrtle, and the Charleston-dancing baby clown, Charlie Ed. It’s his metal statue that you can see on Van Horne Street across from the rail museum.

In desperation, circus boss Zack Terrell contacted U.S. company headquarters where the chief elephant wrangler, “Cheerful” Gardner, dropped everything and hopped a biplane north. Forced down by bad weather outside Denver, Colorado, he transferred to train and reached Cranbrook a week later. By that time three of the elephants had been returned to the fold, the first taken in a swamp just south of town and the last pair cornered and corralled by Ktunaxa trackers at a ranch near the St. Mary’s reservation.

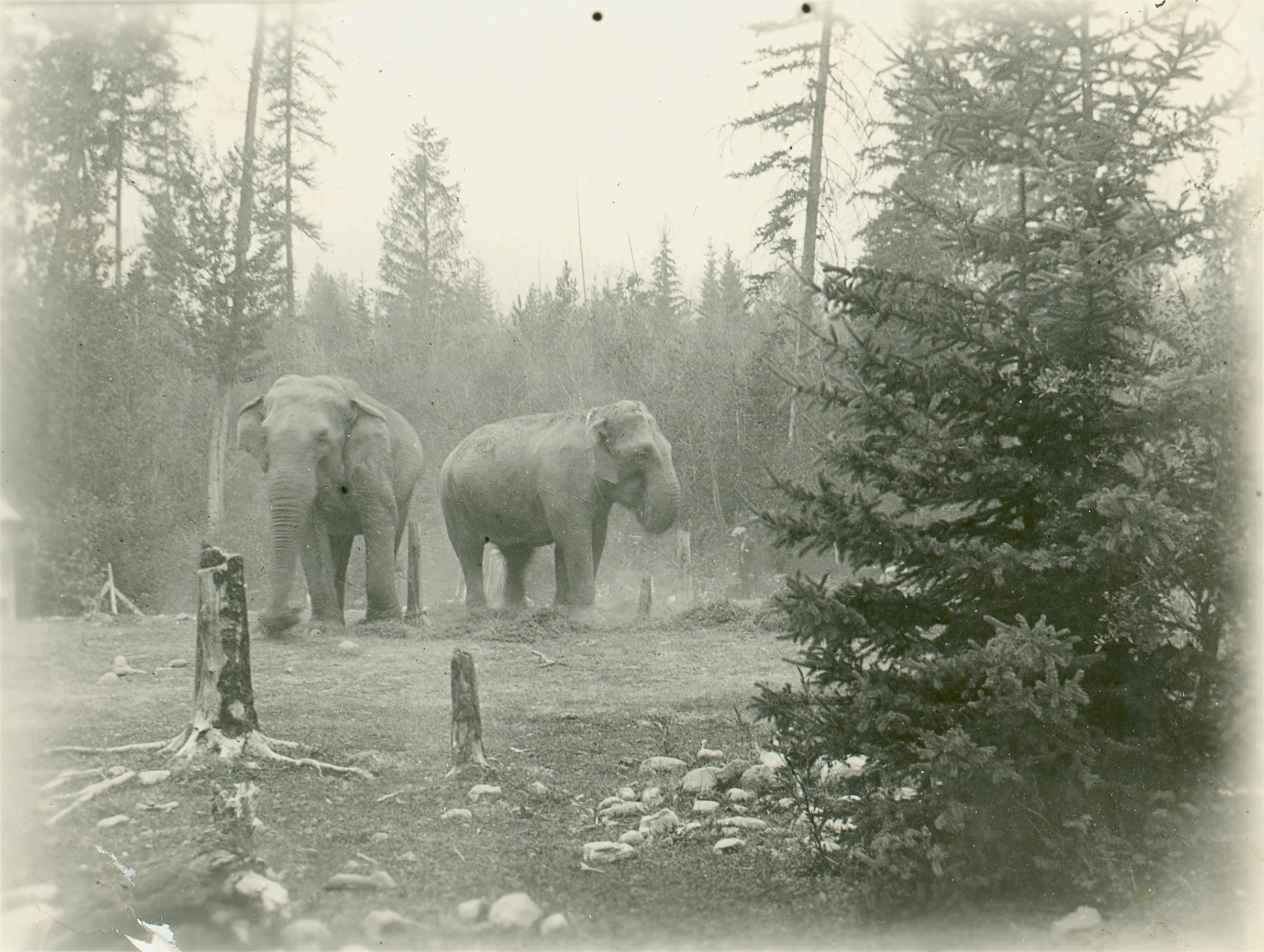

Despite the offer of a $200-a-head reward, no further progress was made for the next two weeks. Hoping that the smell of camels, with whom the elephants were accustomed to bed down at night, would lure them into the open, a stakeout was arranged at an abandoned mill where tracks had been discovered—without success. At last, facing the devastating loss of $60,000 worth of livestock, Gardner departed with the bulk of the elephants, leaving Terrell to carry on the search.

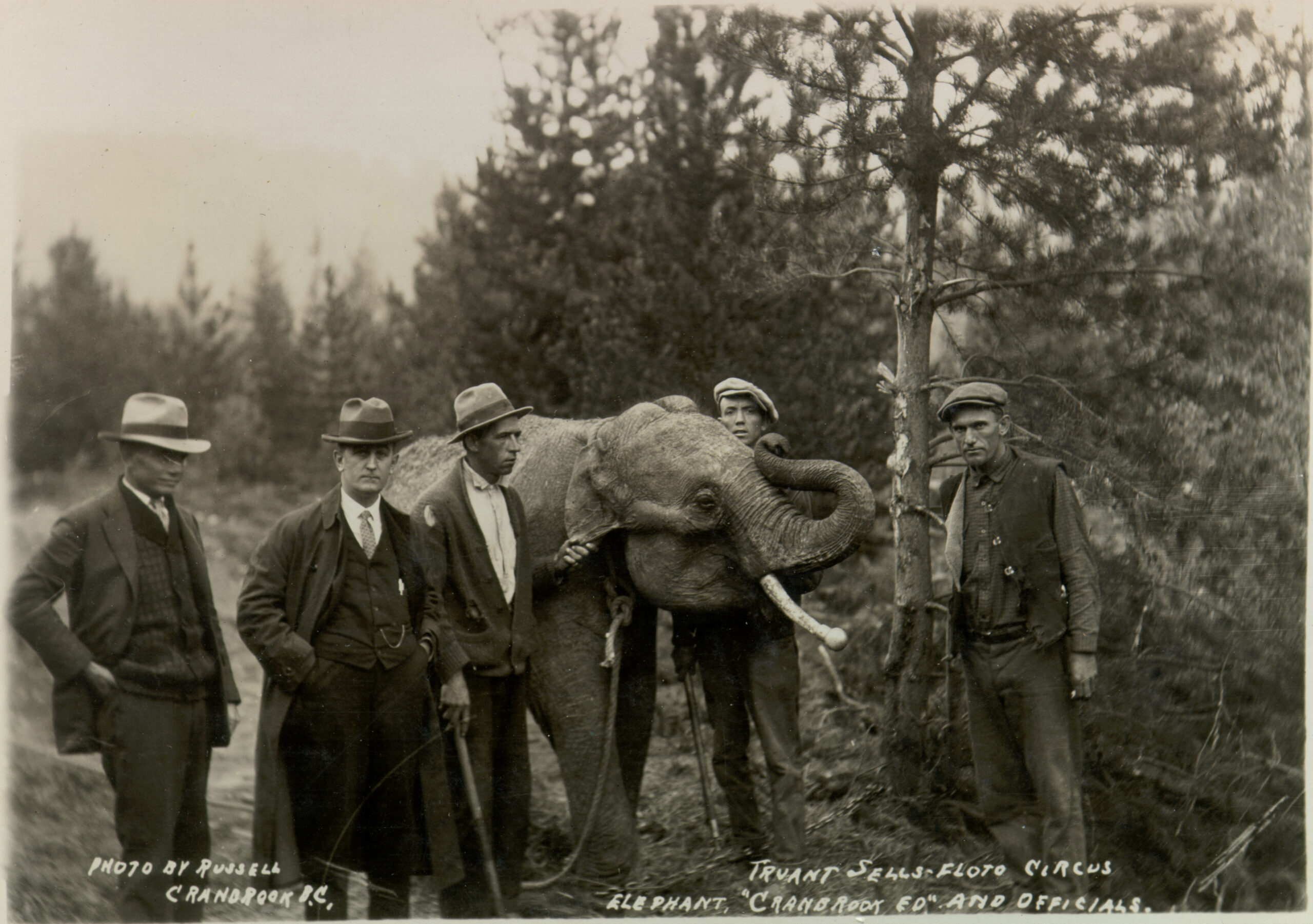

Two of the Sells-Floto elephants being used as lures for Myrtle and Charlie Ed. “The Stakeout.”.Courtesy of the Columbia Basin Institute of Regional History.

As the temperature of late summer nights steadily dropped, hope faded with it, and a fickle public turned its attention to more lofty matters. After all, just around the corner loomed a momentous federal election, upon which, as usual, the fate of the nation hung. Only this time it really did.

Called the constitutional crisis, or the King-Byng Affair, it was a complicated business. Dogged by a scandal involving malfeasance in his own customs ministry, Liberal Prime Minister Mackenzie King called an election, hoping to win a majority and sweep the whole mess under the carpet. Unfortunately for him, he came in second to Arthur Meighen’s Conservatives. With support of a third party, however, King persuaded Governor-General Byng to allow him to form a minority government and stay on as prime minister.

From there, things went from bad to worse until King found himself facing a vote of censure that would have forced his resignation. He preemptively resigned and told Byng to call another election. But Byng refused and handed the premiership to Meighen. King cried foul, claiming a functionary appointed by the English government had no right to ignore the advice of a duly elected Canadian prime minister. After manoeuvres too complex for a story about elephants, an election was called with, according to the Liberals, the issue of Canadian sovereignty at stake.

Then, out of the blue, the following offensive headline appeared on the front page of the Nelson Daily News: “Indian Squaw Captures Elephant With Apples.” Below it was an account of how Tilly, located by a party of Ktunaxa “scouts” led by an unnamed woman, was lured with apples close enough to be roped and tethered. For good measure, the circus men, when they finally arrived, were forced to pay her an extra $10 to lead the reluctant elephant back to town.

The story was vehemently and indignantly denied by the circus folk who claimed complete credit for Tilly’s capture once the Ktunaxa had located her. Was the story a newspaper reporter’s fancy? Or was this a face-saving cover-up?

Now only Myrtle and Charlie Ed remained at large, ironically the two biggest attractions of the show, known for their Charleston-dancing prowess. But the first week of September passed, bringing ever-colder nights and no sightings. Then, a few days before that momentous federal election, Myrtle was discovered near Gold Creek, at the foot of Moyie Mountain, gaunt, stricken with pneumonia, and suffering from two bullet wounds to her leg. An attempt was made to lead her out of the bush, but she soon collapsed and died.

Myrtle was skinned by a local taxidermist and displayed in a store window. Her head found its way to the zoology department of the University of Alberta. The rest of her body remained where she died, a feast for passing carnivores. Hunters soon learned of their presence, and several grizzly bears were shot as they gorged on her flesh. Only her bones remain, somewhere among the pines.

It was now almost six weeks since the stampede, and only the baby clown, Charlie Ed, had managed to stay free. Soon the cold and diminished food supply would kill him. Efforts were redoubled as local farmers were recruited with the promise of a recaptured Charlie appearing at the upcoming Cranbrook Fall Fair. Finally, he was found, none the worse for wear, and he grudgingly rejoined his keepers when they and a group of Ktunaxa trackers found him on the shores of nearby Jimsmith Lake.

The promise was kept, and Charlie once more became the star of the show, this time of the town’s fall fair. On opening day, Cranbrook’s mayor, Tom Roberts, poured a glass of champagne over the little fellow’s head, declaring him to be known henceforth as Cranbrook Ed, a moniker that remained forever enshrined in Cranbrook lore but was quickly forgotten everywhere else.

As a final touch, Mrs. Roberts was about to present a bouquet to the winner of the Popular Girl contest (the one who sold the most raffle tickets), when Charlie intervened, snatched the flowers from her hand, and flung them at the feet of the astonished young woman. Or he may have eaten them, newspaper reports being notoriously unreliable.

As for the election, the local Liberal candidate, Dr. James Horace King (no relation), won by a hair and ended up, after an illustrious career, as Speaker of the Senate.

Richard Rowberry’s new novel Frank and the Elephants is a mostly true story based on the entirely true story of the Cranbrook elephant stampede.