If you grew up in Western Canada, chances are you’re already familiar with the work of Francis Rattenbury.

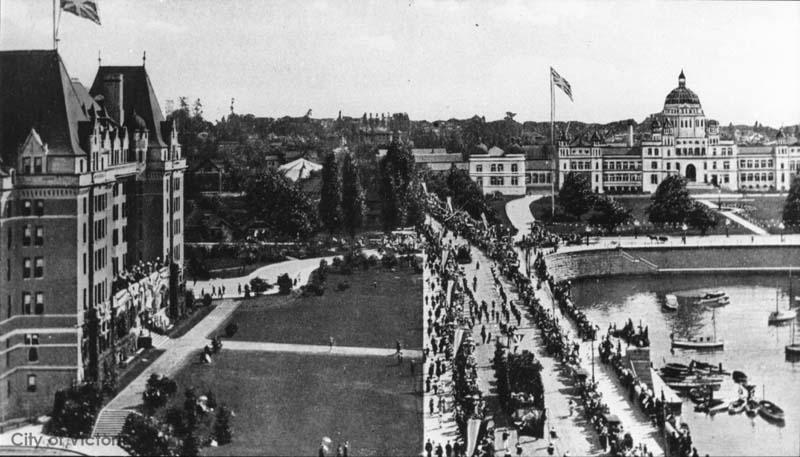

Even today, the buildings he designed are amongst the most memorable in the region, from the Vancouver Art Gallery, to the Roedde House Museum, to the Chateau Lake Louise. He also left an indelible stamp on his adopted hometown of Victoria—most prominently in the inner harbour, where he designed both parliament and the Empress Hotel. For the better part of 20 years, “Ratz,” as he came to be known, was British Columbia’s preeminent architect, a man of grand imagination and even grander ambition whose life went on to inspire multiple books and even an opera. But the story of Rattenbury has a dark side; it’s the tale of a man driven to succeed at all costs; of bankruptcies and ruined lives; and of arrogance, corruption, scandal, addiction, sex, and murder.

“It’s a universal story,” notes composer Tobin Stokes, who wrote the aforementioned opera and speaks over the phone from his home of Victoria. “It’s the story of a man out of balance with himself. A man whose ambition is so large, it ultimately destroys him.”

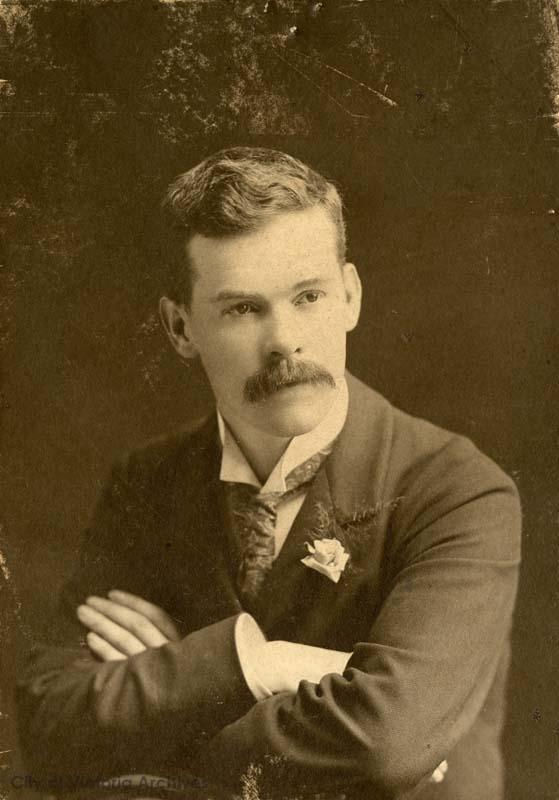

Rattenbury was only 25 when he arrived in Vancouver in 1892. Born in Leeds, he’d made the jump across the pond in hopes of capitalizing on the building boom that had gripped the region over the previous six years, beginning when Vancouver was designated as the western terminus of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). A shameless self-promoter, he placed an ad announcing himself in the Vancouver Daily World, fudging his credentials to claim he’d trained under renowned architect Henry Lockwood (who had died when Rattenbury was still a boy). And although an economic depression stalled his initial ambitions, Rattenbury swiftly turned his attention to something far grander.

That year, a contest had been announced, soliciting designs to replace Victoria’s much-loathed parliament buildings. Rattenbury’s submission—one of 66 applications from around the world—was characteristically ambitious: a 600,000-square-foot facility in a style described by the judges as “a blending” of the Romanesque, Classic, and Gothic. After two rounds of voting, the 25-year-old Rattenbury was declared the winner, and from there, his career rise was nothing short of meteoric. For nearly 20 years, he would win virtually every commission he went after, working on projects for a number of high-profile clients, including the provincial government and the CPR.

Unfortunately, thanks to Rattenbury, most of those projects were a nightmare. For one thing, he was a control freak; he tinkered with his designs constantly, ordering costly and last-minute changes, rejecting materials that had already been purchased, and locking horns with anyone who dared question his vision. For another, he had a habit of underestimating costs in order to win commissions, and then saddling his contractors with any overruns—something that forced at least one of them to the point of bankruptcy. As more and more people began to discover, Rattenbury was a deeply unpleasant person; a man, historian Terry Reksten would note in her 1977 biography, whose “character has received universally bad reviews.”

“Residents of Victoria BC who remember him are quick to admit that he was a genius,” she wrote, “but he made few real friends, more than his share of enemies, and those who became close with him were left embittered by the experience.”

Stokes is blunter in his assessment. “Oh, he was a dick,” he says with a laugh. “He was going to take on anyone who stood in his way.”

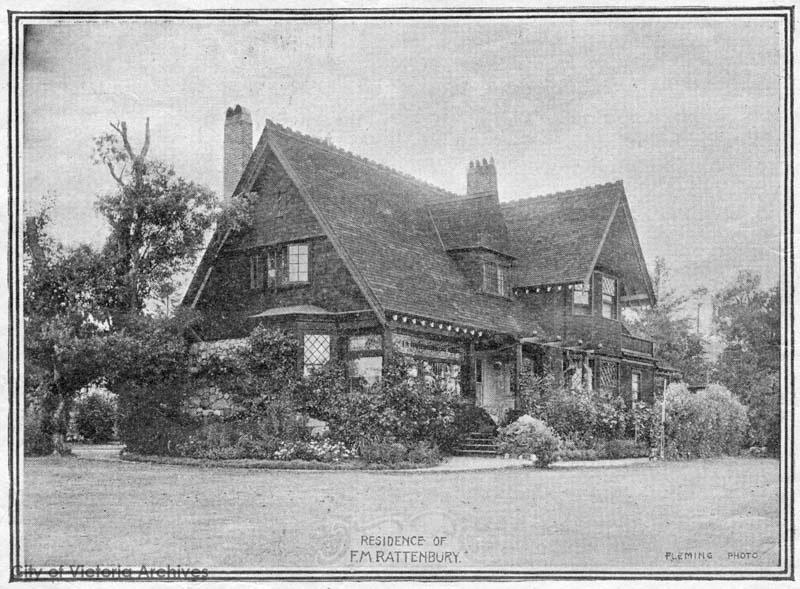

By the time parliament was completed, Rattenbury had married Florence Nunn. The timing of their wedding was suspect for the era; roughly seven months later, their first child was born. That Ratz wasn’t exactly a considerate husband was apparent during their honeymoon: six days in a tent in the Chilkoot Pass, a gruelling trail to the Yukon where an avalanche had recently claimed the lives of 60 people (having recently invested in business ventures in the region, Rattenbury feared that news of the disaster would discourage prospectors from venturing northward, and undertook the trip so that he could write about it in glowing terms).

Despite his personal failings, Rattenbury’s star continued to rise throughout the early 1900s. In 1901, he won a competition to design Victoria High School, and also became the CPR’s western division architect. The latter victory would allow him to truly test the scope of his vision, designing elaborate tourist hotels and resorts in cities across the country. In 1903, he received the commission to design the Empress. In 1905, he won a contest to design the Vancouver Courthouse (today the home of the Vancouver Art Gallery). The year 1906 was looking to be a banner one for the almost-40-year-old Rattenbury, and according to his friend William Oliver, he rang it in with aplomb: “Rattenbury’s dress coat, which was brought in for the occasion, was hanging in rags when he left,” Oliver wrote in a letter to a friend. “I was surprised to find so much spirit of abandon still lurking in lads from 38 to 55.”

But 1906 wasn’t, it would turn out, a banner year. Nor were many of the ones that followed. In October, frustrated with what he saw as undue interference in the design of the Empress by the CPR’s head architect Walter Painter, Rattenbury left the company. He also lost two design competitions (one in Ottawa, and another in Saskatchewan). He was tolerated by his peers, owing to his wealth and influence, but rumours of graft and unscrupulous behaviour continued to dog him. He’d been accused of colluding with school board officials on more than one occasion, in relation to winning the contract to build Victoria High; he’d similarly been accused of abusing his position to snap up a commission to build Government House in Victoria. There were even criminal allegations that he was using kickbacks to line his own pockets (and in some cases, materials from a job to renovate his own home).

Things continued to decline in subsequent years. While commissions from existing projects were enough to keep him afloat, he designed very few buildings during that time. A promising job as the architect for the Grand Trunk Railway fell apart after its general manager Charles Hays went down with the Titanic. Rattenbury nearly went bankrupt when land he’d purchased along the rail line was appropriated by the government to re-home veterans. His marriage, too, was in shambles; by 1912, he and Nunn weren’t speaking, forcing their daughter Mary to carry messages between the two.

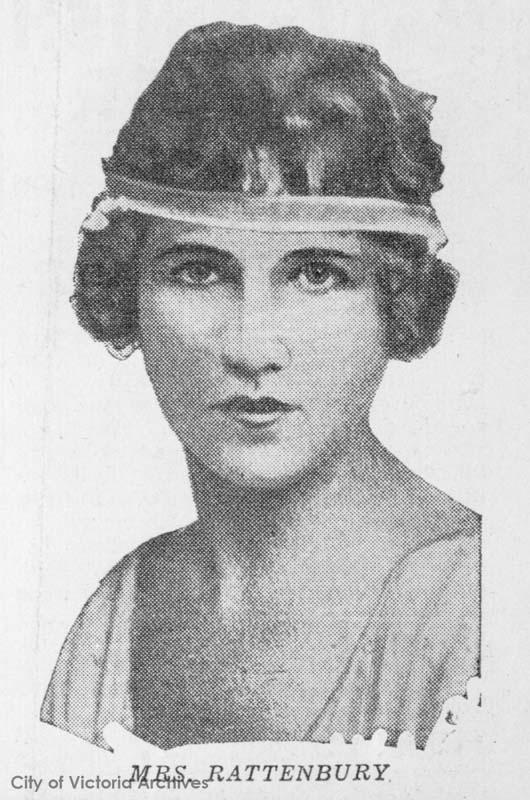

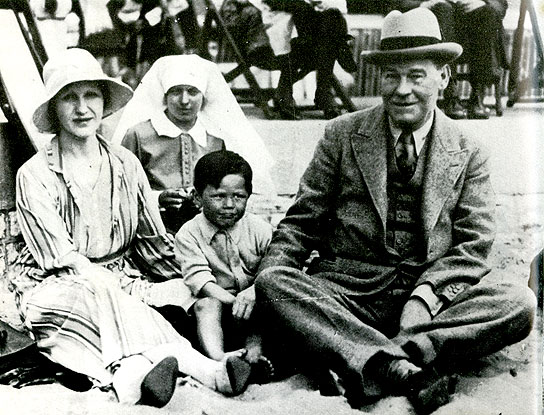

By 1920, Rattenbury was 53. Depressed and grouchy, he was known as “Old Ratz” by neighbourhood children, all of whom did their best to avoid him. But then, in 1923, after winning the contract to design Victoria’s Crystal Garden, he met Alma Pakenham. A free-spirited flapper 30 years his junior, Pakenham scandalized Victoria’s upper crust, smoking and drinking in public. Shortly after meeting, the two began an affair—first privately, and then, when Nunn refused to grant Rattenbury a divorce, as visibly as possible. Rattenbury delighted in parading Pakenham around in public, and even bringing her home to drink and carouse late into the night, while Nunn hid upstairs. Their peers were appalled. Victoria society closed its doors to the new couple, and Rattenbury’s reputation as an architect became worthless virtually overnight. Embittered, Rattenbury and Pakenham moved to Bournemouth, England in 1929.

Six years later, Rattenbury would be dead.

It all began with the hiring of 18-year-old George Stoner. Originally brought on as the couple’s chauffeur, Stoner became infatuated with Pakenham—passionately, obsessively so—and by November of 1934, he had become her live-in lover, taking up residence in their spare bedroom. During those years, Rattenbury’s mood grew darker and darker. Their finances were dwindling and he was mostly deaf. Always a heavy drinker, he now spent most evenings in a drunken stupor, often threatening suicide. According to testimony given at her 1935 trial (more on that soon), the affair between Pakenham and Stoner was quietly condoned by Rattenbury, on account of his failing health and the difference in their age. Unfortunately, neither of them quite understood the depth of Stoner’s jealousy, or his capacity for violence. Emotional, and not particularly bright, he would fly into a rage anytime Pakenham suggested they break off their affair, and on one occasion, he even tried to strangle her.

And on March 24, 1935, he took things further still.

Sometime during that afternoon, Rattenbury had, in an uncharacteristic display of vulnerability, spoken obliquely to Pakenham about her affair. It’s highly likely, according to Reksten’s biography, that the pair then had sex, and that the perceived rekindling of Pakenham’s relationship with Rattenbury drove Stoner into a rage. Early that evening, he threatened her with a revolver; sometime after 10 p.m., he went downstairs and caved in Rattenbury’s head with a mallet.

At first, both Stoner and Pakenham confessed to the crime, but it was Stoner who was ultimately found guilty, and sentenced to death by hanging. The trial was among the most sensational to be held at London’s Old Bailey in years, with stories of Stoner’s purported cocaine addiction and Pakenham’s infidelities. Even so, the press, the public, and the courts were sympathetic to Pakenham’s plight, accepting her lawyer’s argument that her confession had been motivated by love for Stoner. After Stoner’s conviction, Pakenham collapsed in the courtroom. Less than a week later, she stabbed herself to death on the shore of the River Avon.

“It must be easier to be hanged than to have to do the job oneself,” she wrote in a note left behind. “One must be bold to do a thing like this. It is beautiful here and I am alone. Thank God for peace at last.”

Due in part to public sympathy regarding Pakenham’s suicide, Stoner’s sentence was ultimately commuted. He was released in 1942 and went back to Bournemouth, where he lived an uneventful life—until he was convicted of indecent assault in 1990, being found naked in a public restroom with a 12-year-old boy. And while Rattenbury’s life ended more than 80 years ago, public fascination with him endures (Stokes’s opera, for example, was sold out for the duration of its run in 2017), a character immortalized not only in books and art, but in the buildings he left behind: imposing creations that serve as reminders of both his architectural prowess and his very human failings.

“The way I see it is, he killed himself,” Stokes says. “The other guy did it, but in the end, he’s responsible for all the misery and unhappiness which led to his ultimate demise. It was all to do with his outsize ambition.”

Learn more about local history in our Hidden Vancouver series.