Buzzing gently, she uses her strong mandibles to cut out a round piece of leaf the size of her own body, tumbling briefly before catching herself and hovering in the air. She flies back to her solitary home in the crevice of a fence, bellyboarding on her leaf circle. Here, she’ll use the leaf to wallpaper her home along with petals and her saliva, making space for a ball of pollen in which she’ll lay a single egg. Then she’ll use more leaves and petals to create a wall to separate the growing larva from its siblings. A single nest can contain as many as 20 leafy nurseries, together looking like a rolled-up cigar. When the new bees are grown, they will break out of their brown leafy pellets, wipe pollen from their faces and antennae, and fly off to start the cycle anew.

This bee is a leafcutter, one of the family Megachilidae, which includes resin bees and mason bees. Leafcutters aren’t like the familiar honeybees that build waxy hives in huge colonies; they are solitary, nest in small cavities, use leaves or dirt to build homes, and, most importantly, are native to British Columbia.

And while honeybees receive most of the love and attention from beekeepers, the hundreds of species of native bees in this province, including hairy belly bees, pollen pants bees, masked bees, and cuckoo bees, are often ignored—even as they are endangered due to climate change and human extraction of natural resources.

Marika van Reeuwyk loves the Megachilidae because of the interesting nesting materials they use, such as the fibres from woolly plants that wool carder bees use to line their nests. She and a small group of other bee enthusiasts formed the Native Bee Society of British Columbia because, she says, the existing bee organizations and associations in the province often focus on honeybees and not native bees. Their one-year-old society has members who are artists, scientists, educators, authors, beekeepers, and farmers. They welcome anyone who has a passion for preserving pollinators within the province.

A collection of mason bees. Photo courtesy of Lori Weidenhammer.

Growing up in Agassiz, Van Reeuwyk and her twin sister were fascinated with insects and would try to build ant farms. “We really wanted ants to live in our room. It was never successful,” she laughs.

This enthusiasm for bugs changed when, as a child, Van Reeuwyk walked across the lawn at a swim club potluck and accidentally stepped on a bee. The bee stung her big toe. “It was really little, and I remember the feeling of that pain. I think that really started instilling this fear in me, towards bees especially.”

Her childhood curiosity wasn’t reignited until a coworker at Camp Jubilee caught a moth in the dining hall and showed it to her. Her initial horror changed to fascination when she saw its cute fuzzy face, like an alien with antennae.

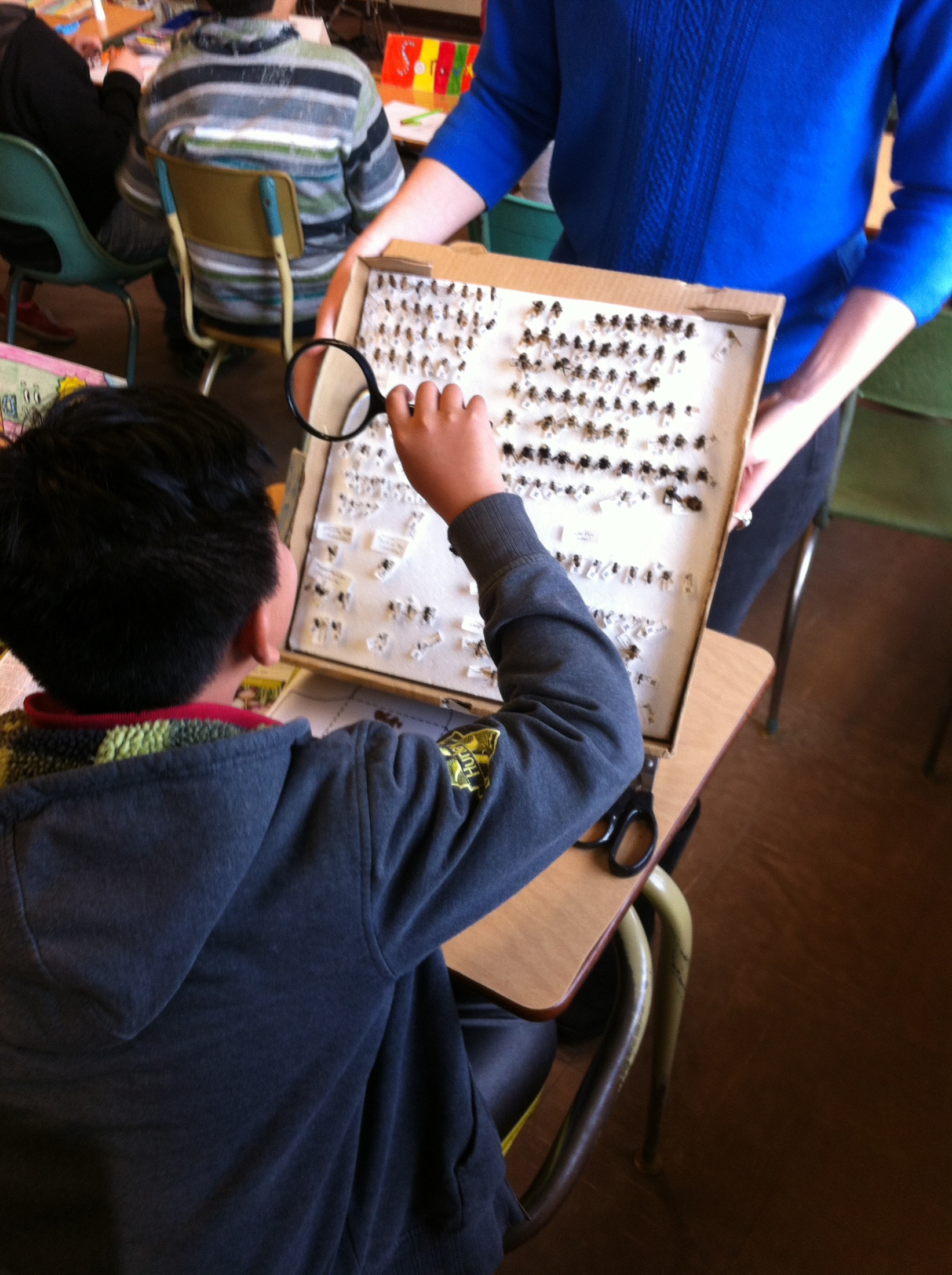

Van Reeuwyk’s love affair with bees started when she volunteered with the Environmental Youth Alliance during college, where she helped plant food gardens at elementary schools around Vancouver. Erin Udal, one of the facilitators, brought in a pizza box one day, and Van Reeuwyk said, “Oh, you brought some pizza for us.”

“No, actually, this is my bee box.”

Udal lifted the lid and presented rows and rows of bees. There were more than 50 insects, Van Reeuwyk said. She was dazzled by the variety of colours and shapes. The tiny ones started at half a centimetre and grew to larger bumblebees that were almost two inches long.

She asked Udal, “Are these all bees?”

“Yeah.”

Van Reeuwyk thought to herself, “Wow, there’s so much more to bees than I used to think.”

Erin Udal shows off her pizza box of bees to a student. Image courtesy of Erin Udal.

Udal’s mentorship changed Van Reeuwyk’s perspective on bees and expanded her knowledge of native species. Taking a beekeeping course in 2015 got her used to holding honeybees in her hand and having thousands of them swarming around her head.

These days, Van Reeuwyk focuses on wild bee conservation and doesn’t beekeep anymore.

When she’s in the field, she wears normal clothing with a net in hand and an EpiPen in her pocket (she’s allergic to honeybees, and there’s currently no test for stings by native bees). She says the bees are unlikely to sting when you’re near flowers because they are paying more attention to their food. She searches for native bees, which she places in a clear glass vial to be photographed from several angles. Then she releases the bees and uploads the photographs to iNaturalist, an online community science platform where global specialists can help identify and verify her findings. The submissions can also be used for research.

Sarah Johnson, president of the Native Bee Society and a biologist who specializes in bumblebees, says all bees face complex challenges, including climate change, pesticide use, habitat loss, pathogens, and diseases.

Native bees are important because they are the ones doing most of the pollinating within the province, not honeybees, and they have been doing it for thousands of years. As their numbers shrink, honeybees cannot replace them, and maintaining biodiversity is necessary for ecosystem stability. Knowledge is power, Johnson says, and the society exists to bridge that knowledge gap, dispel myths, and allay fears.

“The majority of bees would have no reason to sting you because they don’t really have those large social nests to defend.”

Bumblebees are the only native species that live in colonies of 60 to 200 bees. That’s smaller than honeybee colonies, which can grow to several thousand bees.

The Native Bee Society’s vision for the future is one where native bees are thriving and protected for their own value, not just their value to humans.

Van Reeuwyk suggests some gardening tips for keen native bee supporters in the city this fall. The first is to keep a messy garden because bumblebees like to hibernate under leaves and in dead stems. (Let your lawn grow!)

If you want to provide more sustenance for pollinators, Van Reeuwyk says it’s best to grow flowers that will bloom all season, two or three species at a time. Plant in large clumps so that pollinators are attracted to the feast and can fly easily from flower to flower. Also plant different colours, shapes, and sizes because different bees have different-shaped bodies and tongues. Some species also have different dietary needs and won’t be able to live in an area if its food source is unavailable.

Native plants such as goldenrod, Oregon gumweed, or Douglas asters, can be planted as seeds in September or October, and left over the winter. All of this can be overwhelming, so Van Reeuwyk suggests creating or finding a personal bloom calendar that tracks when flowers bloom. To support spring and autumn bees, she advises including flowers that bloom in early spring and autumn when fewer flowers are available.

To learn more, the Native Bee Society has resources on its website and all events are open to the public.

And as Van Reeuwyk says, in peace and pollen.

Read more Community stories.