It may seem hard to believe today (pandemic notwithstanding), but Vancouver was once a hotbed of happening clubs. In his 2019 book Vancouver After Dark, author and local historian Aaron Chapman chronicled the city’s once-vibrant nightlife and lamented the dozens of clubs that have disappeared. In this story from our archives, Chapman pays tribute to three memorable venues.

A far cry from the scornful No Fun City label of today, mid-century Vancouver was a parade of colourful proprietors, wild stunts, and now-vanished venues.

With names like The Egress, The Retinal Circus, and Oil Can Harry’s, these establishments were plentiful—live music was everywhere, and the weekend’s happenings were vividly detailed by saloon columnists like Jack Wasserman and Denny Boyd. “I feel like the No Fun City label has always been a great falsehood,” says local historian Aaron Chapman, who has authored three books on the city’s nightlife. “I was born and raised in Vancouver, and there’s always been something going on. There’s plenty of fun to be had. In fact, if I sat down with my doctor, he’d probably tell me I’ve had far too much fun in the last 20 years.”

In that vein, Chapman’s 2019 book Vancouver After Dark (Arsenal Pulp Press) takes a detailed look at the city’s nightlife in years gone by—with a particular emphasis on the dozens of clubs that have disappeared.

“Some are still there, and there are lots of new places,” Chapman notes via phone. “But there just so many, from The Cave, to Richard’s on Richards, to the Town Pump and the Starfish Room, to Luv Affair—and a hell of a lot of others—that have disappeared. They really had something; they caught a vibe that people in Vancouver haven’t forgotten.” Detailed below are three such venues from Vancouver’s past (some recent, some distant, all of them departed).

Isy’s Supper Club: 1958 to 1981

For a solid portion of the 1950s and ’60s, Isy Walters was one of Vancouver’s entertainment giants. Born Isadore Waltuck in Odessa, Ukraine (which at that time, was Russia), Isy moved to North America with his parents at age two. He spent much of his life in show business, starting when he was eight years old selling popcorn at The Empress Theatre on Hastings and Gore. At age 14, he ran away to join a travelling carnival (Levette, Brown and Huggins Shows, Inc., derisively referred to by him and his peers as “Lousy, Broke, and Hungry”), and after a lucrative but unsatisfying stint in the scrap metal business during the Second World War, he returned to entertainment in the 1950s, running such venues as the Mandarin Gardens and Victoria’s Sirocco Club (which featured singing waiters). He owned The Cave from 1952 to 1959, and then, in 1959, opened what would be his signature venue: Isy’s Supper Club at Georgia and Thurlow.

“Isy Walters’ story is really interesting,” says Tom Carter, an author, musician, and member of the BC Entertainment Hall of Fame. “And from what I can tell, he was a really nice guy.”

Isy’s Supper Club. Photograph courtesy of Tom Carter.

“These guys were, in a way, celebrities themselves, because of their personalities,” Chapman adds. “They were so much more colourful than the WASPy people who ran Vancouver at the time. When it comes to running a nightclub, it takes a certain kind of person to be able to do that. Guys like Isy Walters or Joe Phillipponi aren’t going to be allowed to be a railroad executive, or the equivalent of Chip Wilson. You’ve got these immigrant families getting into these businesses, because it was easier for them to get into than a ‘straight’ business.”

Even though Walters was not a drinker, he had a knack for the nightclub scene, and Isy’s (alongside The Cave and Marco Polo) quickly became one of the city’s preeminent spots for entertainment both wholesome and risqué. Described by the Vancouver Sun’s Jerry Wasserman in 1966 as a “sometime scrap dealer, all-purpose hustler and full-time showman,” Walters received B.C.’s first and third liquor-by-the-drink licenses (for The Cave and Isy’s respectively), and made sure that the 1,000-seat Isy’s showroom regularly featured live music, Vegas-style entertainment, and big-name musical acts like Buddy Rich, Duke Ellington, and Little Richard. The club also hosted comedians who would go on to be world-famous, such as Lenny Bruce and Richard Pryor (Pryor even babysat Walters’ children, taking them on a trip to the Stanley Park zoo, before being fired in 1969 for swearing onstage).

“Apparently in those Pryor shows, there was silence a lot of the time,” Chapman says. “Because people didn’t know how to react. I was interviewing a guy who was at one, and he was saying that the only person laughing in the entire bar was the bartender. I’m sure [Pryor] had that reaction elsewhere to a certain extent, but it captures a bit of what Vancouver was like at a certain time—before we were quite so culturally hip.”

Throughout the decades, Walters was a constant presence at the club that bore his name. He repaired costumes and worked on sets; in 1969, he bailed out the Four Tops quartet after they were caught with marijuana and a gun. He put his children to work in the clubs, and later brought his son Ritchie in as a partner. That said, his judgement wasn’t always solid. In fact, he once took out a newspaper ad declaring that one of his acts, a roller-skating stripper, was “The Worst Show in Vancouver!”

“I’ve spent more than a million dollars on entertainment, and I can tell you I’ve never seen a bad show,” he told Wasserman in April 1963. “Some are just better than others. Of course that’s my way of looking at it—because I can tell you, no operator in his right mind wants to put on a bad show. Believe me, we get sicker than the audience when a show stinks.”

By the early 1970s, Isy’s had fallen on hard times. With entertainment tastes changing, it became Isy’s Strip City, before the venue was sold to Danny Baceda (who had already bought The Cave from Walters and who also owned Oil Can Harry’s). While Walters intended to retire, and even threw himself a giant farewell party, he was back within a year, serving as Baceda’s general manager.

“I remember they had these giant plywood girls on the roof,” Carter says with a laugh over brunch at the historic Sylvia Hotel in the West End. “They were all sparkly, and really quite attractive. And I remember driving by, and seeing Isy’s Strip City and going, ‘What’s that?’ And my parents went, ‘Don’t look at that.’” Walters died in the club in 1976. And while it continued to operate until 1981, it was subsequently torn down to make way for the Shangri-La. Two of the plywood figures are now on display at The Penthouse Nightclub on Seymour.

Luv-a-Fair: 1975 to 2003

The unassuming concrete building near Seymour and Drake went through a number of incarnations during its 40-plus-year lifespan: first as a jazz club, then as a gay bar, and then, throughout the ’80s and ’90s, as one of the city’s most legendary venues. The high-energy nightspot was well-known as a hotbed of sex, drugs, and (alternative) rock ’n’ roll.

“For the not-yet-jaded or weary, it was the Vancouver night scene’s most thrilling spectacle for most of three decades,” wrote the Sun’s Kerry Gold in a 2003 retrospective. “For a good many Vancouverites from disco age and younger, the heyday of the Luv-a-Fair at Seymour and Drake was the heyday of Vancouver’s club scene.”

Located in Yaletown, Luv-a-Fair featured an upstairs mezzanine and pool table, a “goth box” near the dance floor for the city’s black-lipstick crowd, and bathrooms that were notorious for illicit sex and drug use. The big music speakers were regularly draped with drag queens and dancers, and the stage showcased an impressive array of live acts, such as the Violent Femmes, Sonic Youth, and Nine Inch Nails (who, according to Gold, performed there in 1989 to approximately 100 people). Musicians even frequented Luv-a-Fair when they weren’t performing, including U2, The Pixies, Blur, and Depeche Mode—who, Gold also wrote, danced on the club’s speakers to one of their own songs.

It had been purchased in 1975 by the Kerasiotis family—six brothers whose first hospitality venture was Olympic Pizza on Broadway in the mid-1960s—who paid approximately $1 million for the defunct nightclub (then called The Garage). While it initially played disco and catered to a mostly gay clientele, Luv-a-Fair quickly became a place where all club-goers partied side by side. However, by the late ‘70s, the Kerasiotis family had decided to move away from strictly disco music, which caused a bit of a stir.

“There was this wonderful moment where the older disco crowd—the people listening to Gloria Gaynor or something—their time had passed,” Chapman says. “The gay clientele in the club had gotten smaller, and some of the new-wave music fans had come in. And those club-goers got fed up with the DJ, and staged a sit-in. They filled up the dance floor and wouldn’t dance until somebody changed the music. Overnight, that DJ was dismissed, and next thing you knew, the Gloria Gaynor record was smashed, and a whole new wave took over. I haven’t been able to nail down exactly when it happened yet, but it was a real D-Day kind of event.” (Note: Gold’s version of the story states that it was actually fans of fired disco DJ Richard Evans who staged the sit-in, in protest.)

Luv-a-Fair remained a popular destination for the city’s alternative clubbers, a place where the music was a far cry from the radio hits being played elsewhere in the city. The venue continued to host live music through the 1990s, and closed its doors in February 2003. It was then torn down, to be replaced by a condo tower.

In the ensuing years, the Kerasiotis empire has grown substantially; the family company, Blueprint (founded by patriarch Nick Kerasiotis’s sons Bill and Chris), is among the largest entertainment conglomerates in B.C., hosting hundreds of annual events and owning multiple clubs including Celebrities, The Charles Bar, and Venue. The family also runs local restaurants, such as Sopra Sotto and Nammos Estiatorio.

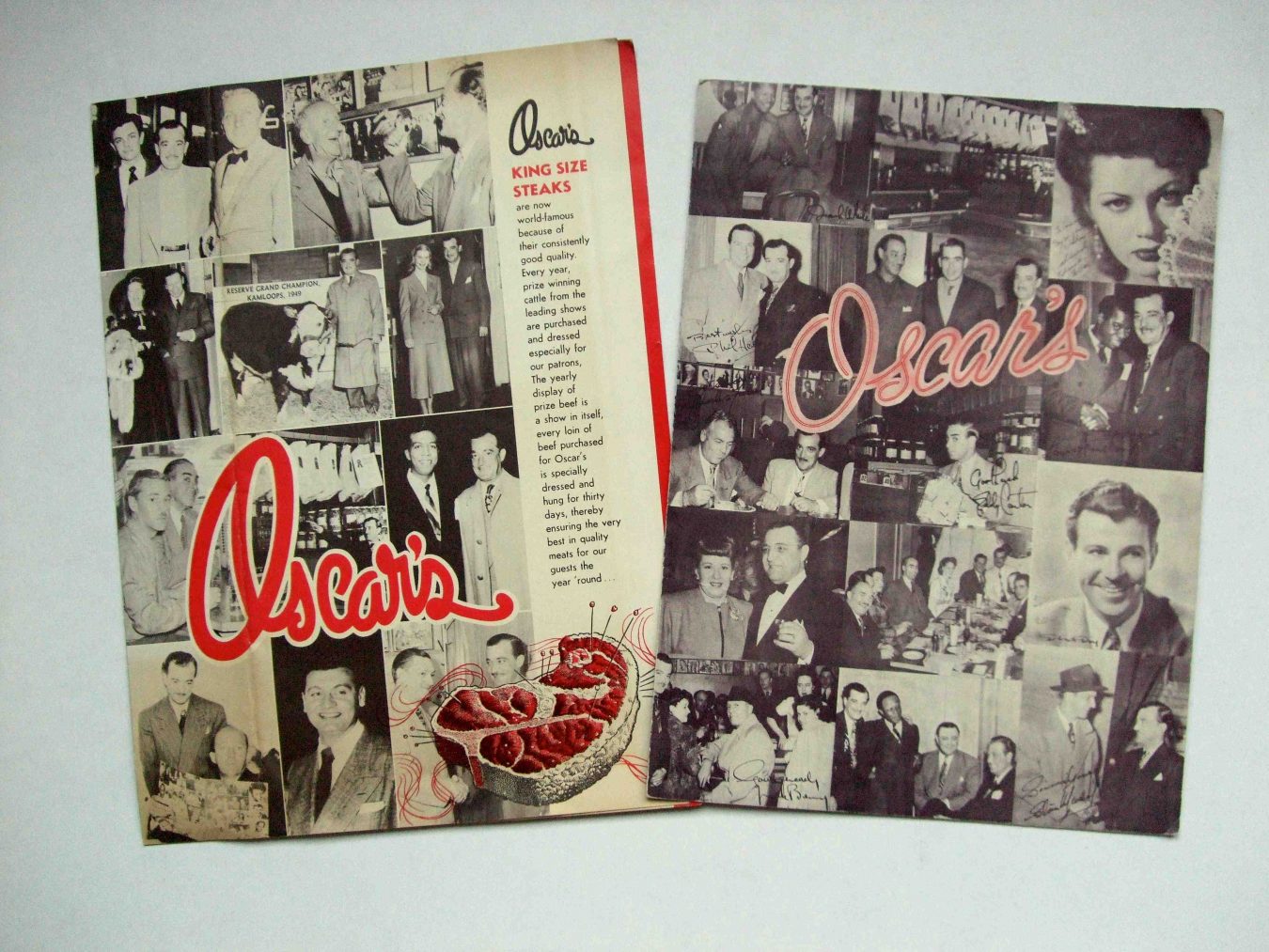

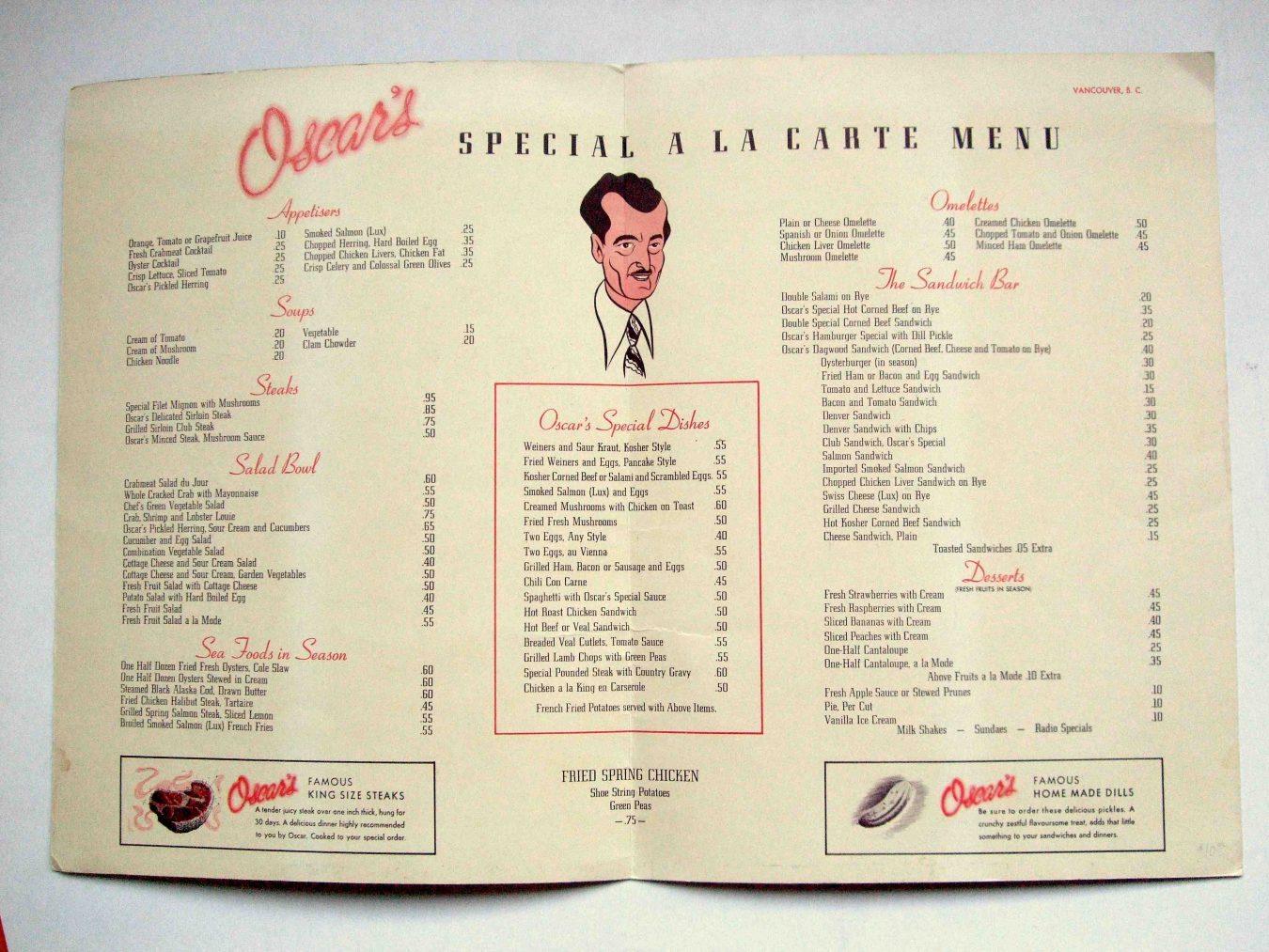

Oscar’s Steakhouse: 1940s to 1964

Down the street from then-legendary Palomar Supper Club on Burrard and Alberni, Oscar’s Steakhouse was a place notable as much for its menu as for the host of celebrities who dined inside. In fact, the stretch between Oscar’s and The Palomar was once known, according to Sun columnist Denny Boyd in 1985, as “the most exciting piece of sidewalk in Vancouver,” and the steakhouse’s storied entrance hall contained dozens of pictures of proprietor Oscar Blank, posing with every famous person who had walked into his business.

Oscar’s Steakhouse. Photo courtesy of Tom Carter.

“Oscar was a bit of an autograph hound,” Carter says, chuckling. “He liked to get photos of himself with celebrities. [The late Vancouver bandleader] Dal Richards was telling me about one: Dal was backing up Bing Crosby at the Forum in the early ’50s, and Oscar was waiting for Dal to bring Crosby in so he could get a picture. They got delayed, and Oscar thought they weren’t coming, so he started drinking—and when they finally did show up, Oscar was totally annihilated. So the picture is of Dal, Dal’s wife, Bing Crosby, and a gal from Shaughnessy that Crosby was screwing around with. Crosby is leaning back, because he didn’t have his toupee on and he didn’t want people to see his bald head. And they’re holding Oscar up, because he’s completely shit-faced. If they’d let go of him, he would have fallen over.”

Blank himself was a character just as colourful as the celebrities he posed with; he gained his unusual last name after his Russian parents Solomon and Clare accidentally left the surname field blank on their immigration forms (Blank claimed he was an orphan, a story which was widely believed for years). Born in Winnipeg on the wrong side of the tracks, he had nonetheless grown into a dapper man, sporting colourful ties and a pencil-thin moustache. Starting with a simple sandwich shop, he quickly built it into the city’s first classy steakhouse, featuring king lobster, New Zealand crab, and grain-fed steak that was hung and aged for 30 days.

A shameless self-promoter, he would give away his neckties at the end of each night, and was well-known for his practice of trotting over to the Hotel Georgia, getting into the elevator, and declaring, as if to himself, “I think I’ll head over to Oscar’s for a steak!” Tragically, Blank’s life was cut short in 1954 when he and 36 other passengers were killed in a horrific mid-air collision above Moose Jaw while Blank was visiting his dying sister. He was 45.

Photo courtesy of Tom Carter.

“It was a particularly horrible plane crash,” Carter says. “In fact, it’s recognized as one of the most gruesome in Canadian history.” After, the business was run by Blank’s widow, who moved it across the street to 1023 West Georgia before selling it to then-Capilano Suspension Bridge owner Rae Mitchell. Mitchell kept it open for close to a decade, before competition from other restaurants forced it to close. And the original Oscar’s location was torn down, with the present Burrard Building constructed in its place in 1955.

Like any big city, Vancouver is rapidly changing. It is exciting to see progress, but that doesn’t mean we have to forget what came before.

This article from our archives was originally published on January 20, 2019, and updated on May 17, 2021. Read more Community stories.