The city of Victoria had not seen anything like it since the days of the gold rush. Hockey fans began lining up before daybreak at the doors of Plimley & Ritchie, a downtown sporting goods store on View Street. A queue of men three deep stretched down the block, around the corner, and down the next street.

Mail and telephone orders were banned, so eager fans had to show up in person. Businessmen hired day labourers to queue for tickets on their behalf. With police minding the door, the men were allowed inside the store to buy tickets to the opening game of the Stanley Cup finals scheduled for the following night.

After two hours, all 4,000 reserved seats had been sold. Several hundred standing-room tickets would be sold at the arena just before game time.

One hundred years ago in late March 1925, the storied Montreal Canadiens arrived in the British Columbia capital after travelling for days by train and boat to defend their Stanley Cup championship from the previous year. The storied Flying Frenchmen boasted the scoring prowess of speedy Aurèle Joliat and the young Howie Morenz, known as the Stratford Streak. The defence was anchored by captain Sprague Cleghorn playing in front of the great netminder Georges Vézina, so cool in goal he was known as the Chicoutimi Cucumber.

On the long train ride westward, the players relaxed by playing cards in the smoking car and listening to records played on a phonograph. They were crossing Alberta when newspapers across the country carried a story reporting the cocky Canadiens were confidently predicting a three-game sweep of the best-of-five series against the Victoria Cougars.

On arrival in British Columbia, Montreal co-owner and general manager Léo Dandurand denied his team was taking their rivals for granted. “Let me say right now that we are looking for a spirited series with every game a battle,” he said. His Victoria counterpart agreed. “The teams play much the same type of hockey and both have bundles of speed,” Cougars owner and general manager Lester Patrick said. “Both defences block and rush well. Every game should be contested on even terms, and I don’t look for heavy scores.”

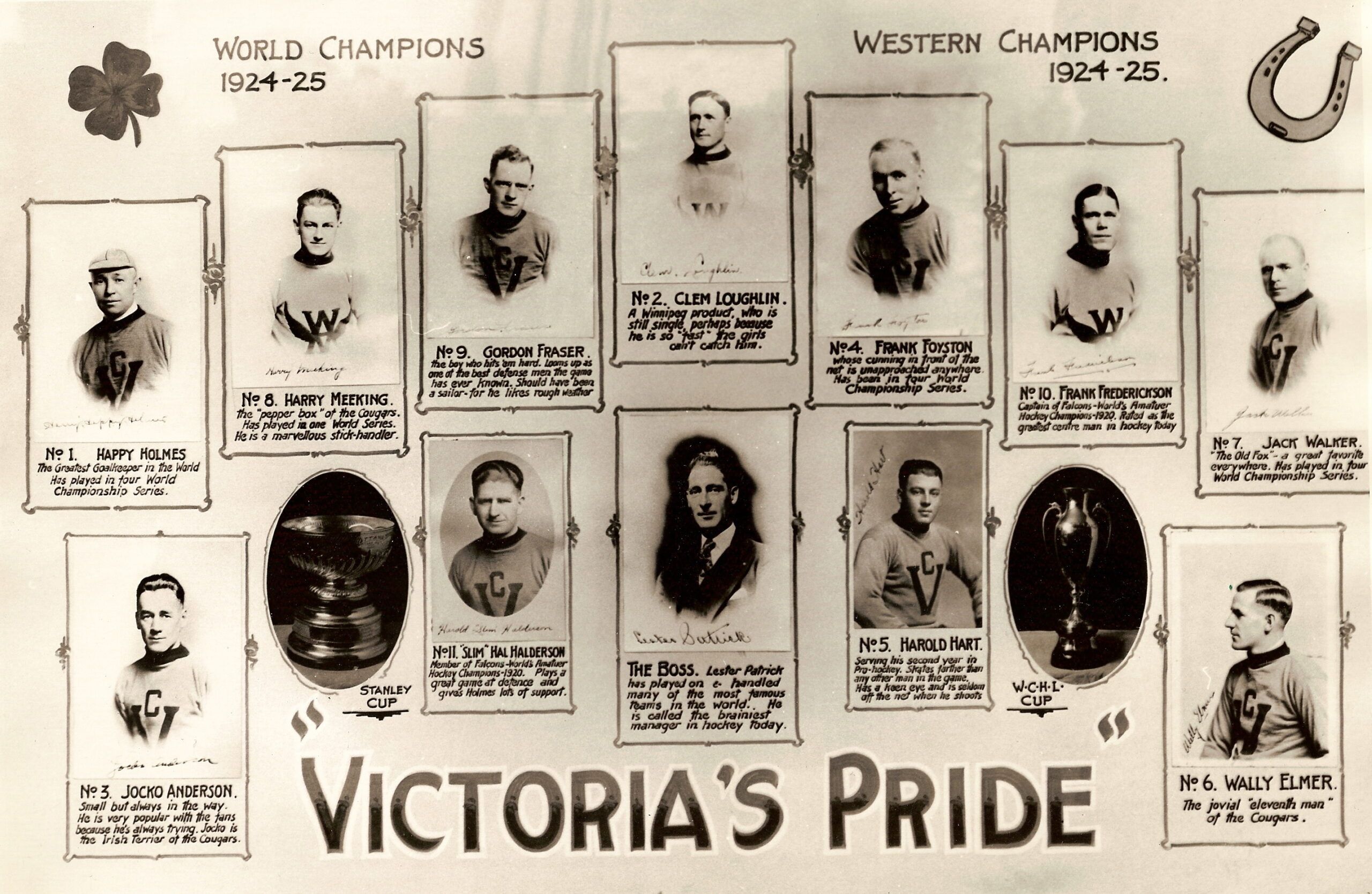

The Cougars, champions of the Western Canada Hockey League, greeted the visitors after they registered at The Empress Hotel. The Victoria side perhaps had less flair in their play, though more experience. Centre Frank Frederickson and defenceman Haldor “Slim” Halderson won Olympic gold medals representing Canada in 1920 while on the roster of the Winnipeg Falcons, an amateur team of First World War veterans of Icelandic origin. Centreman Frank “the Flash” Foyston had earlier won Stanley Cups with the Toronto Blueshirts and Seattle Metropolitans. Goaltender Harry “Hap” Holmes was seeking a fourth Stanley Cup championship on a team that had not won any.

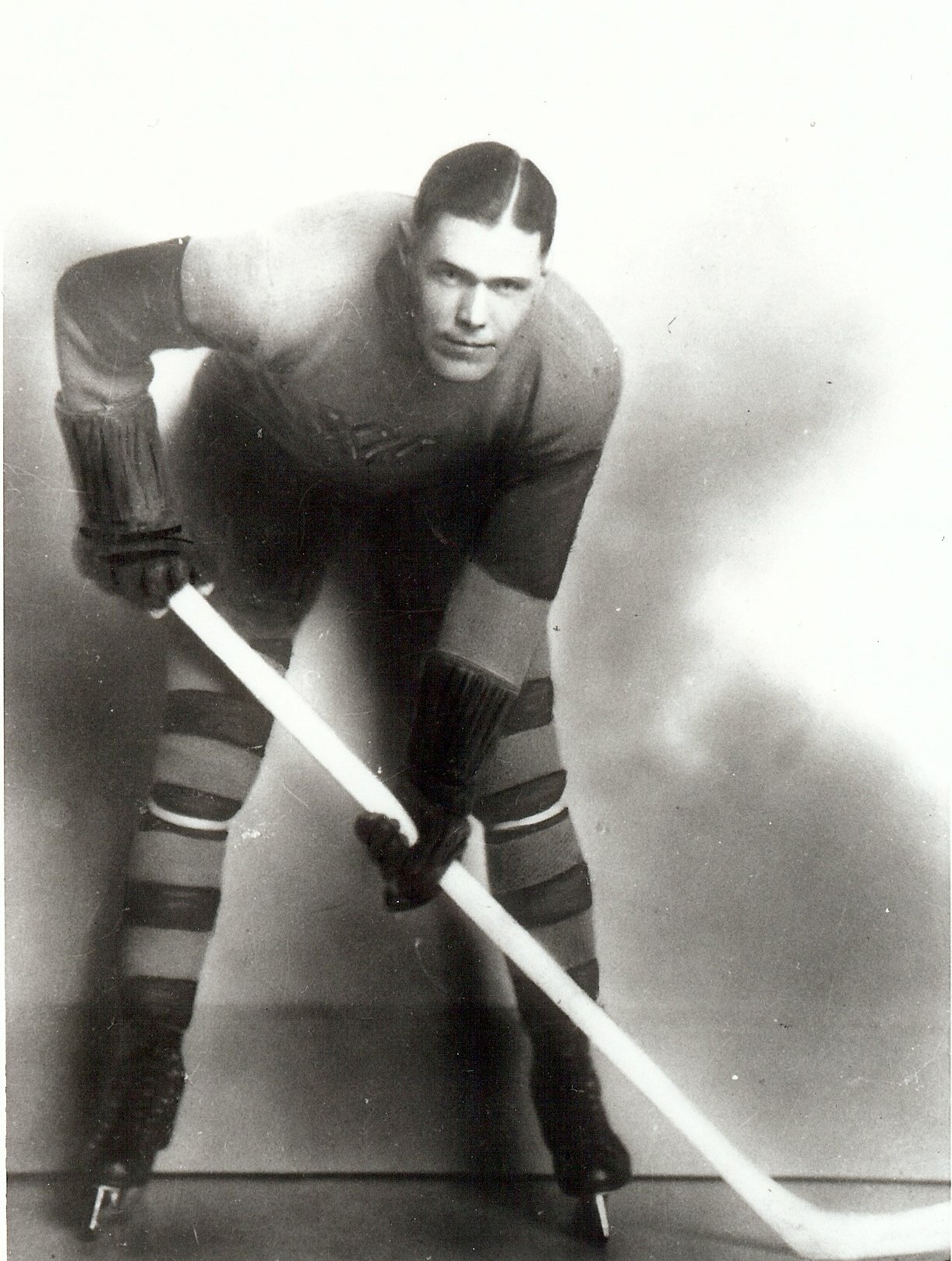

Frank “the Flash” Fredrickson of the Victoria Cougars.

Game 1

Cougars 5, Canadiens 2

An exuberant crowd gathered at the Willows Arena (also known as the Patrick Arena and Victoria Arena) on Cadboro Bay Road in suburban Oak Bay, a 15-minute streetcar ride from downtown. The seats reserved for the fans who had lined up the previous day cost $1.25 (about $20 today). For 25 cents, spectators could buy a 12-page coloured program featuring lineups, photographs of the players, and a chance to win $54.50 in prizes from local merchants, including Two Jacks Dope, a popular tobacconist.

“I’d like to be in there playing tonight,” Victoria’s Patrick said, “but I guess at my age it’s better to pay someone else to do the work.”

The inaugural game was played under Western rules, which allowed forward passing anywhere on the ice. Eastern rules forbade such passes in the attacking zone, so stickhandling and a rugby-like approach remained typical features of play. The rule book would alternate for each game in the series.

The Cougars wore blue-and-gold sweaters with a large V and small C crest on the chest, while the Canadiens wore their familiar colours of bleu, blanc, et rouge. The game was not yet four minutes old when Jack Walker opened the scoring for Victoria. The visitors never seemed comfortable defending as they struggled to cope with an unfamiliar approach to the game. The Canadiens were also hindered by the pesky backchecking of Victoria’s forwards throughout the game. Victoria led 4-0 before Montreal finally scored past the midway point of the third period.

Victoria’s general manager also surprised the Canadiens by changing his players every 10 minutes or so, while some Montreal starters played the entire 60 minutes. He was not surprised that his players stunned the Canadiens. “It’s a better team than lots of them gave us credit for having,” Patrick said.

Game 2

Cougars 3, Canadiens 1

The Denman Arena in Vancouver.

The action shifted to Denman Arena in Vancouver, a much larger venue than the Oak Bay arena. About 12,000 fans crowded the 10,200-seat building in what was believed to be the largest audience at the time to ever witness a hockey game in Canada.

Once again, Walker opened the scoring. After rushing past the Canadiens defencemen, he swung around behind the Montreal net. As he emerged on the other side, Vézina made a fateful mistake by skating slightly toward the shooter. Walker banked the puck off the goalie’s side and into the net. After he shot, he was the victim of “one of the crudest and most brutal assaults seen on the ice here,” according to one newspaper account, when crushed into the boards by Montreal bad boy Billy Boucher. Walker collapsed on the ice but returned to play defence, sporting a bruised hip and a skinned knee.

Game 3

Canadiens 4, Cougars 2

Back in Victoria with a championship in sight, the Cougars fell behind on Morenz’s opening score, later responding with a goal by Jocko Anderson. Harold “Gizzy” Hart scored for the Cougars early in the third period. The next 10 minutes were frantic, as Joliat and then Morenz scored for the Canadiens before Morenz completed his hat trick and sewed up the game with a late goal. Dandurand’s pregame pep talk, during which he waved telegrams sent by Montreal fans (and, undoubtedly, gamblers), sparked his team. The game was broadcast by the CFCT radio station with a mandolin orchestra providing entertainment between periods.

Game 4

Cougars 6, Canadiens 1

The Cougars came out flying in the fourth game, with Frederickson scoring five minutes into the first period. A late goal by Flash Foyston at the end of the second period seemed to settle the matter. Downtown at city hall, a council debate over sewer bylaws was interrupted when the city clerk whispered into the mayor’s ear. “Gentlemen,” the mayor announced, “the score’s four to one in the second period.” Another update was given midway through the third, while the final score was greeted by a resolution congratulating Patrick and his players.

The Canadiens struggled to keep up with a terrific pace maintained by the Cougars, who regularly substituted players. “They skated like fiends, passed the puck like masters, shot like machine guns, and their defence was as hard to penetrate as the side of the battleship,” Archie Wills wrote in an uncredited story for The Victoria Daily Times. Dandurand said, “We were outclassed.”

Each of the Cougars players earned a $352 bonus, while the defeated Canadiens got $234.60. A happy city honoured the Cougars with a banquet, where Foyston and Gordon Fraser were presented with gold lockets. The engraving read: “Victoria Cougars, World’s Hockey Champions, 1924-25. Presented by the Citizens of Victoria, B.C.” The other players would have to wait for their souvenirs as there had not been enough time to engrave them all. The mayor also presented left winger Hart with the puck used in the final game, which was decorated in the team’s blue and gold colours.

Five players stayed in the city in the off-season, while the others dispersed to their homes and their regular employment. Clem Loughlin stayed until spring thaw before returning to his farm near Viking, the Alberta town later famous for producing the six Sutter brothers who all skated in the National Hockey League.

The Cougars repeated as Western champions the following season, only to lose the Stanley Cup finals in Montreal to the NHL Maroons. After that season, the Victoria club was sold to business interests in Detroit. In time, the Cougars became the Falcons and are known today as the Red Wings. The highest level of professional hockey would not return to the West Coast until the NHL granted a franchise to the Vancouver Canucks to play in the 1970-71 season.

The Willows Arena burned down in 1929, and Denman Arena suffered the same fate seven years later.

The Cougars triumph marked the last time a non-NHL team won the Stanley Cup. And thanks to the haplessness of the Canucks, the Victoria victory remains the most recent time a B.C. team claimed the iconic trophy.

Mementos from the series are extremely rare. Two ticket stubs (for Games 3 and 4) and a scorecard sold at auction in 2007 for $1,523.85 (U.S.). A program from the 1925 series sold for $1,284.63 (U.S.) at auction in 2016.

Six weeks after the series ended, the Stanley Cup went on display at the same sporting goods store that sold tickets. In 1925 the Cup was a much smaller and squatter trophy than the current one. It was overshadowed in the display by the Merchants Casualty Cup, which stood nearly a metre tall and was donated by an insurer as the top prize for the Western League champions.

That summer, Lester Patrick’s sons discovered the Stanley Cup in the basement of the family home at 242 Linden Avenue in the Fairfield neighbourhood. The boys—Lynn, 13, and Murray, known as Muzz, nine—scratched their initials onto the trophy with a nail. Fifteen years later, as players with the New York Rangers, for which their father was general manager, both got their names on the trophy the legitimate way, by an engraver armed with a small hammer and stencil.

The Victoria Hockey Legacy Society has organized several public events to commemorate the centennial of the Victoria Cougars’ Stanley Cup win, including displaying the storied trophy on March 30.