Before Earls, before Milestones, before Cactus Club Café, there was the Sorensen family. In their heyday, they ran a local restaurant empire that stretched from Hastings Street to the Granville Entertainment District, including four cafés, two bakeries, two restaurants, and a coffee shop, and were what is likely the first restaurant chain in Vancouver history, predating White Spot (which usually gets credited as the first) by almost a decade.

There were three generations behind the chain, Lori Sorensen explains. “My great-grandfather started them, and then my grandfather took over. And then my dad, Keith, took over after that.”

Back in 1911, Lori’s great-grandfather, Thomas Sorensen, arrived in Vancouver with his wife, newborn son, and brother Neil, opening a cafeteria-style restaurant at 124 West Hastings Street—the unfortunately named White Lunch. And this wasn’t just a name: White Lunch was sadly emblematic of the period in which it opened. In the early 20th century, anti-Asian sentiment was rampant in Canada. Vancouver had already been the site of two race riots, and many establishments, including White Lunch, prided themselves on allowing only white servers and white clientele through their doors. However, it wasn’t long before the policy began to rub some locals the wrong way—even those it claimed to benefit.

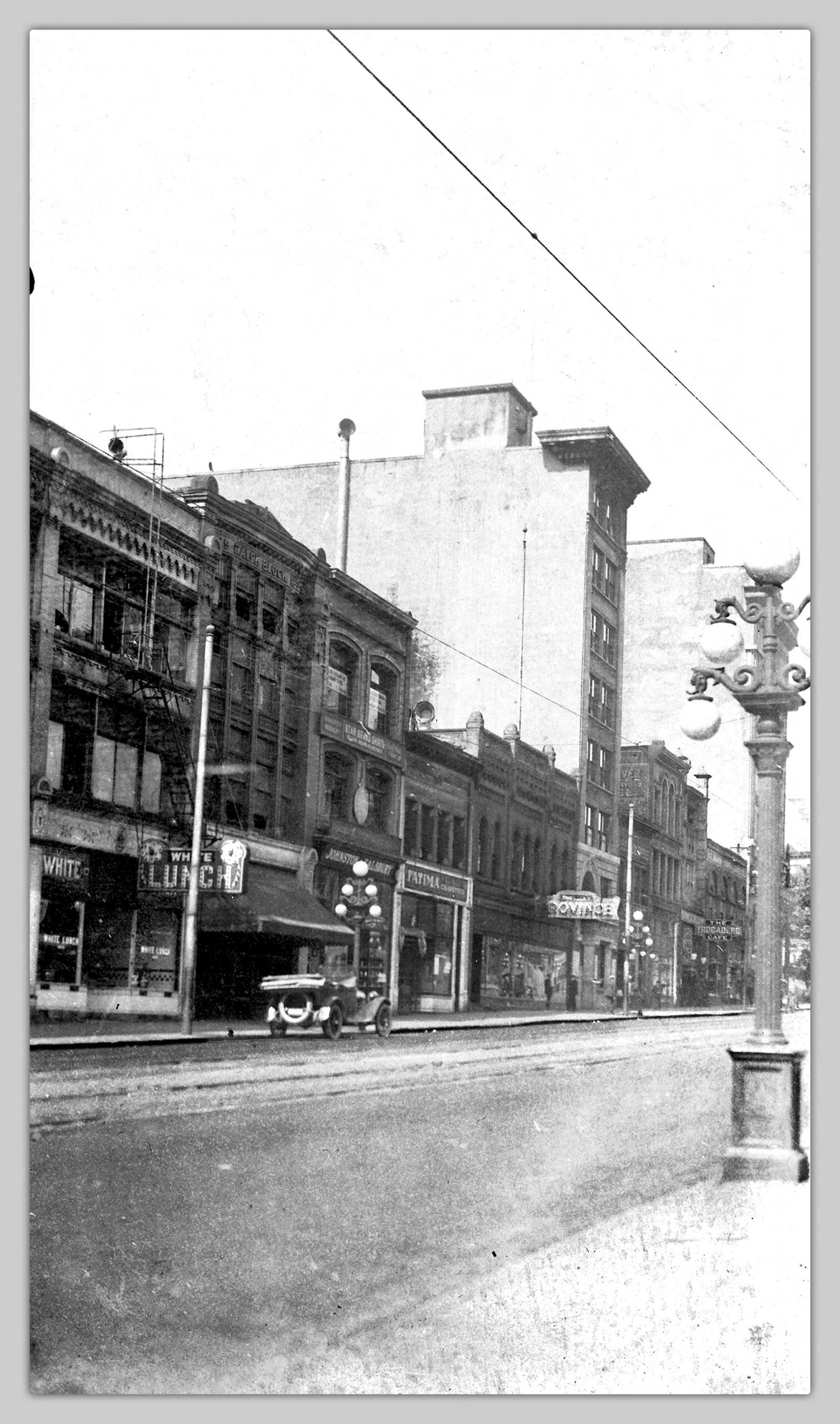

The 100 block of East Hastings Street, including a White Lunch location at an unknown date. Courtesy of the UBC Library.

“Sir,” reads a September 10, 1918, letter from an English resident to the Vancouver Sun, “I read with indignation that the White Lunch people had refused to serve some Japanese businessmen who are in our city on a business trip…. I hope our Japanese friends got better treatment at the next place they called and that they will not go away with the idea that the feeling shown by the owners of the White Lunch represents the feeling of the people here, and I hope our city authorities will see than an apology is offered and that such a thing cannot happen again.”

It’s unclear how long these racist policies remained in effect. In the meantime, company president Neil Sorensen (Thomas was his VP) presided over a period of extraordinary growth—by 1913, there were already three White Lunch locations. In 1916, they added a bakery and acquired a rival business—Boston Lunch—with which they had been feuding for several years. Boston Lunch opened its doors only a few months before the Sorensens, and between 1911 and 1915, the businesses grew in virtual lockstep. As White Lunch expanded, Boston Lunch was never far behind, picking locations suspiciously close to its competitors. In 1915, a Boston Lunch opened roughly a block from an existing White Lunch on Granville Street. Another opened next door to the Hastings Street café.

“The White Lunch and Boston Lunch restaurants are scattered throughout the city and in most cases are in close proximity and rivalry has been keen,” the Vancouver Daily World wrote in August 1916. “They are marked by the similarity of appearance and administration.”

But Boston Lunch’s days were numbered. In the Vancouver Daily World article, Neil Sorensen didn’t deny that “a deal is pending” to “absorb” their competitor. By the end of the year, Boston Lunch was no more, except for a single location—then owned by White Lunch Ltd. After this, Neil Sorensen appears to have stepped back—perhaps because of failing health—and died in 1918 or 1919, leaving his brother Thomas to take over, first as manager, then as president. He served in this capacity for a decade or so before handing control to his son (and Lori’s grandfather) Clarence. While Thomas had, in Lori’s words, “fallen into” the business, Clarence (or Clancy, as he was known) took a more deliberate path. After studying at Harvard, he returned to Vancouver with his new wife, Norma, and took over the family business in 1933.

Staff and patrons in White Lunch at 806 Granville in 1918. Courtesy of the City of Vancouver Archives.

“He was a good guy,” Lori recalls. “He was tall and lanky. He loved his fishing and hunting and all those outdoorsy things. My grandmother—she was probably the driving force in that family, to be honest.”

Under Clancy’s stewardship, the Sorensen chain continued to grow. By the end of the Second World War, its holdings included coffee shops, bakeries, cafés, and the first Clancy’s location, on the 400 block of Granville Street. It wasn’t without hiccups. In April 1937, workers at all White Lunch locations went on strike, demanding better conditions and higher wages. The owners wouldn’t budge—until White Lunch customers themselves refused to cross the picket line. The employees won that battle but were fighting for a new contract all over again within six months.

Nonetheless, by the time the family opened their newest venture, Clancy’s Sky Diner, in August 1949, their empire was thriving, employing approximately 400 people across the city, with two restaurants on Granville Street, a coffee shop on Seymour, two bakeries, and multiple White Lunch cafés.

“At one point, White Lunch had a whole huge operation that produced food for all the chain of restaurants,” Lori notes. “There was a bakery and a dairy. They dealt with all these meats. My dad told me some stories about having to put on hip waders and climb in with the corned beef, but I think it was probably sauerkraut.”

Related stories

- The Highs and Lows of Vancouver’s Air Travel-Themed Restaurant

- The Forgotten Clubs That Brought Vancouver Nights to Life

- Hogan’s Alley—The Tumultuous History of Vancouver’s Once and Future Black Neighbourhood

Around this time, the family also purchased several adjacent plots of land in West Vancouver and built a complex of homes and amenities that allowed all three generations of Sorensens to live in what was essentially a neighbourhood of their own.

“Across the rustic bridge which fords a pleasant stream and up through a natural forest path, you come to the Sorensen’s gymnasium and heated swimming pool where neighbourhood children are privileged to swim,” The Province wrote in an October 1964 profile.

“There was a rhodo garden, and then our house, and then across the street was a forest and a big gymnasium that my grandparents built,” Lori adds. “They were across a creek. That’s where I grew up.”

The family saw continued success through the early 1950s. In 1951, Clarence Sorensen became the head of the Canadian Restaurant Association. The family regularly appeared in the newspapers, known for their lavish barbecues and for Mrs. Sorensen’s forays into the world of painting. There were bumpy patches—including when a Canadian Restaurant Association panel issued a “blistering” report on the state of Vancouver’s restaurants, including theirs—but nonetheless, growth continued. In 1959, Clarence Sorensen handed day-to-day operations over to his son, Lori’s father, Keith, the new general manager.

The ’60s were less kind to the Sorensen restaurants. In 1961, the Seymour Street coffee shop closed. In late 1962, employees of a Clancy’s bakery tried to unionize. The company fired them. After a Labour Relations Board ruling forced them to rehire the workers, they simply closed the bakery. By 1963, the Sorensens had closed the other two. In the mid-1960s, they attempted a rebrand of their Granville Street restaurants, turning them into the Downtown and Uptown Restaurants. It wasn’t enough to save them.

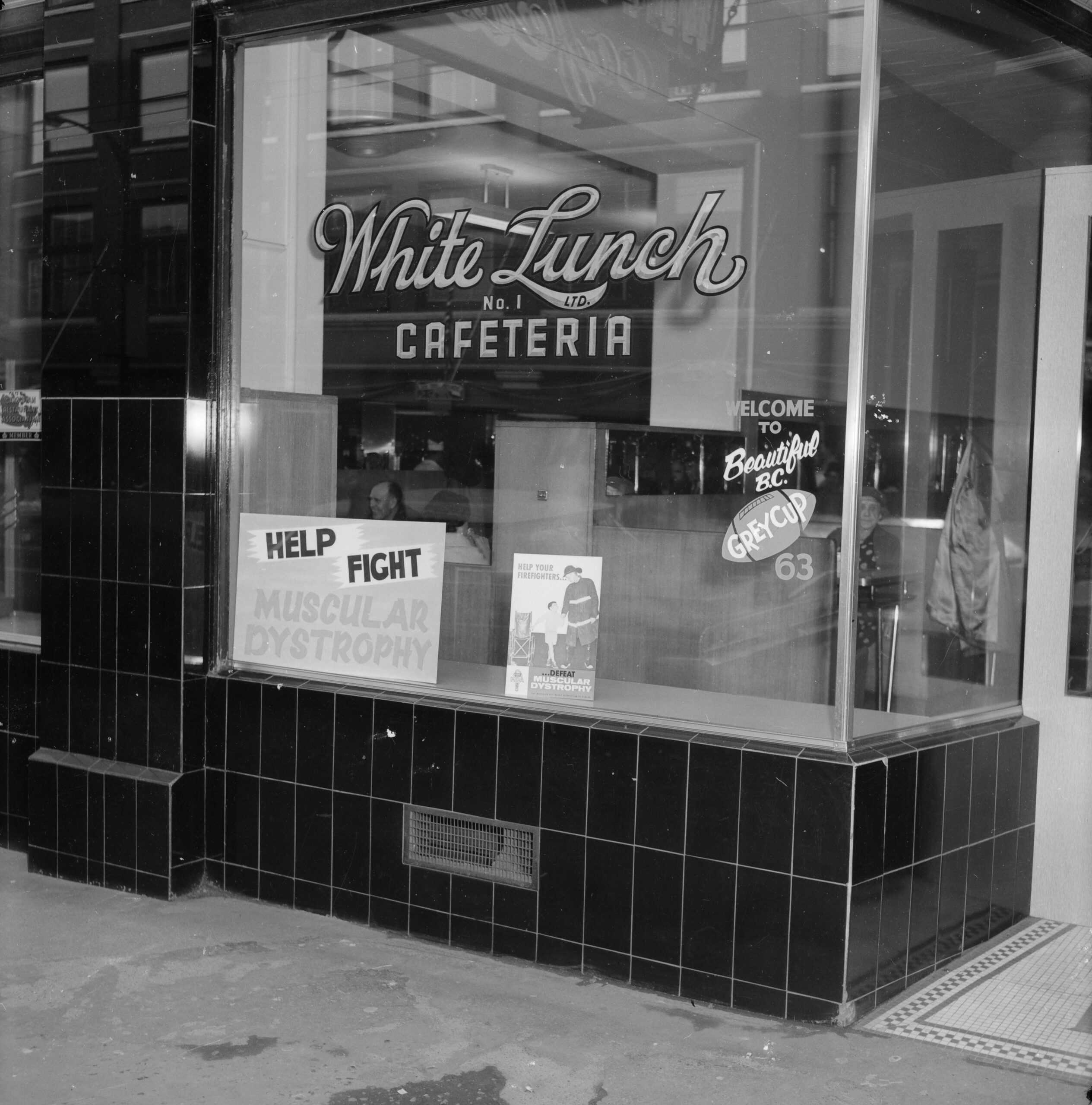

The year 1965 was particularly tough: two White Lunch locations closed, and the Sky Diner was sold. After a brief period under new ownership, it became the site of a finishing school. In the meantime, their businesses had expanded beyond Vancouver—there were restaurants in Kamloops and Williams Lake—but the original White Lunch on Hastings remained the epicentre of the operation, carrying on behind a neon sign shaped like a coffee cup. Lori herself worked there as a child, counting money in a small room above the café for $1.25 an hour.

But Hastings Street in the 1970s was a neighbourhood in decline. By autumn 1970, White Lunch was administering meal tickets to welfare recipients, which caused a further decline in revenues as a fearful public kept their distance. In 1973, Keith Sorensen decided he had had enough. He sold the last remaining White Lunch location—fittingly, given its beginnings, to Chinese businessman Ma To Sang, who relaunched it as a restaurant called the Golden Crown.

At the time, her dad was 40 and had just split with her mom, Lori explains. “He just decided he’d had enough in the restaurant business at that point, I think. A lot of other restaurants had opened up, and the cafeteria-style thing wasn’t really profitable, I suppose. He bought this chunk of land on Hornby Island and became a land developer.”

Today, only remnants of the Sorensen empire remain. The building that once housed White Lunch is now home to a furniture store. Two of the houses on the West Vancouver property, including Lori’s childhood home, are still standing, although they have long since been sold. But in some ways, the Sorensen legacy has continued. Though today she works as a visual artist like her grandmother, Lori and her sister have both run restaurants of their own.

“She had one in Gibsons—it must have been in the late ’70s or early ’80s,” Lori explains. “And I ran my own place in Bamfield between ’95 and ’98. I did the school lunches. We ran events. We had big dinners. It was fun.”

She chuckles. “I think about doing it again sometimes, but then I go, ‘Oh, no. Never mind. I’d rather just be an artist.’”

Read more community stories.