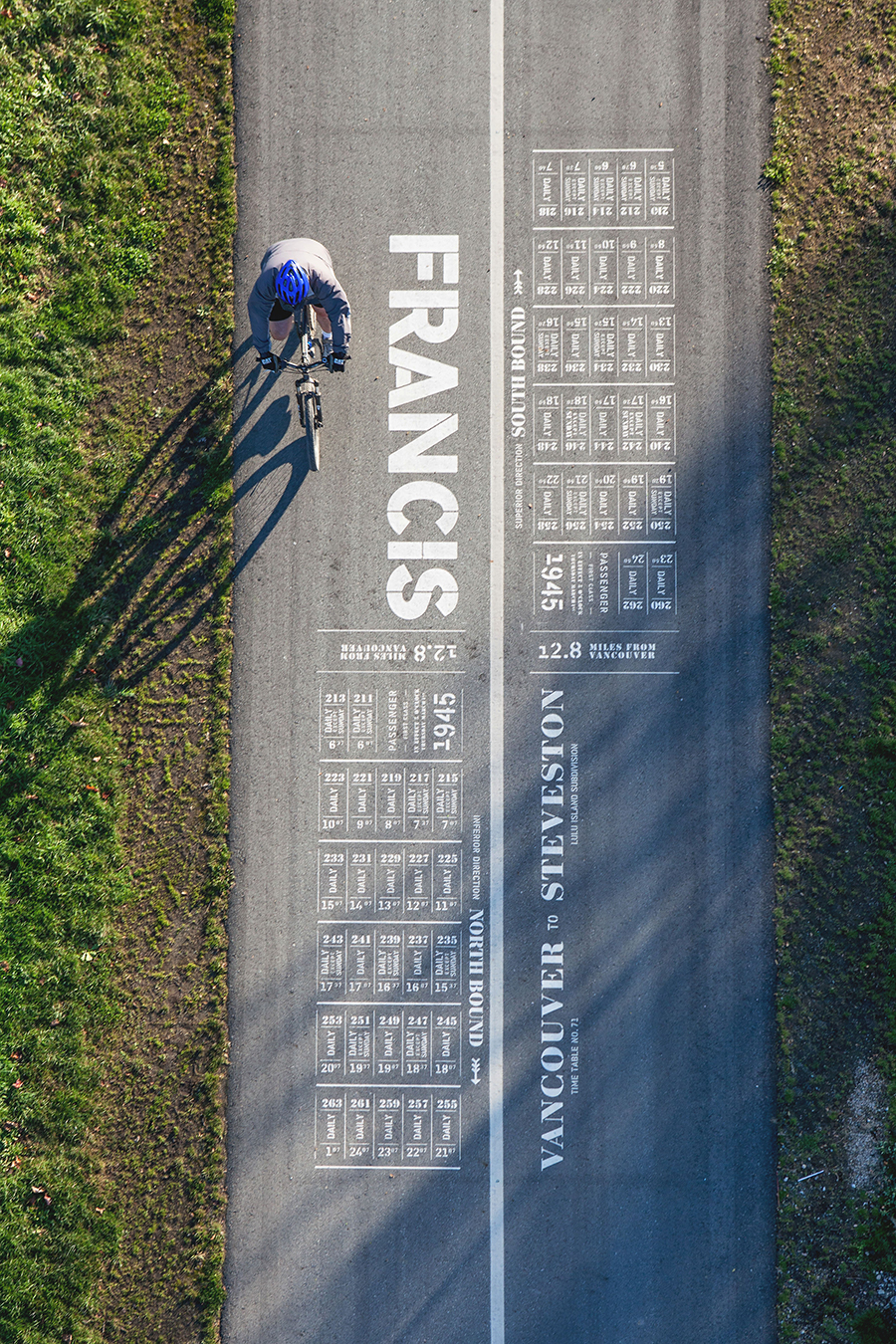

At first glance, Vancouver is a city of infinite spaces. There are mountains, beaches, parks, and those iconic seawall paths. Plenty of room to breathe, sure, but dig a little deeper into the fabric of the city and it can start to look like its public space is coming loose at the seams.

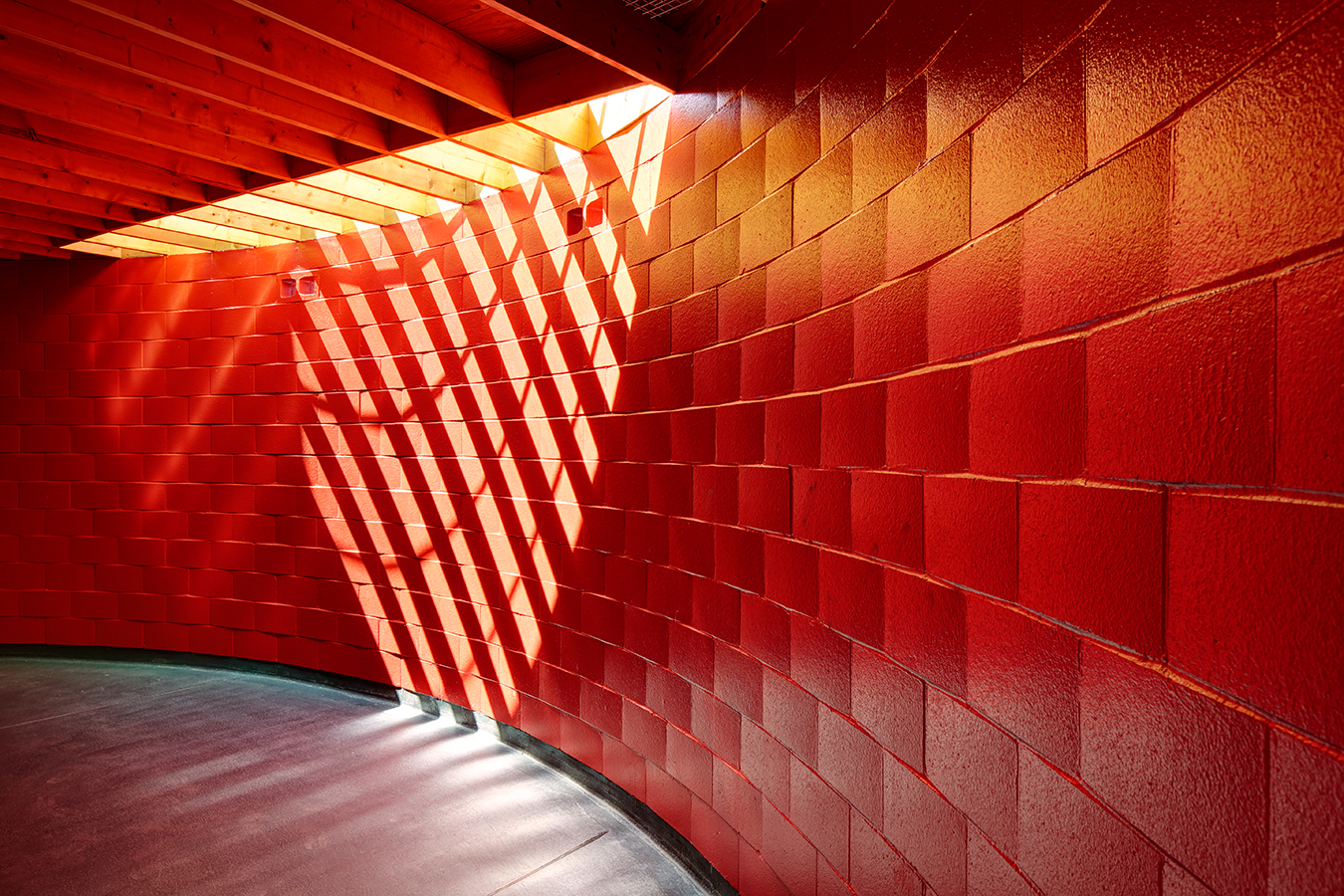

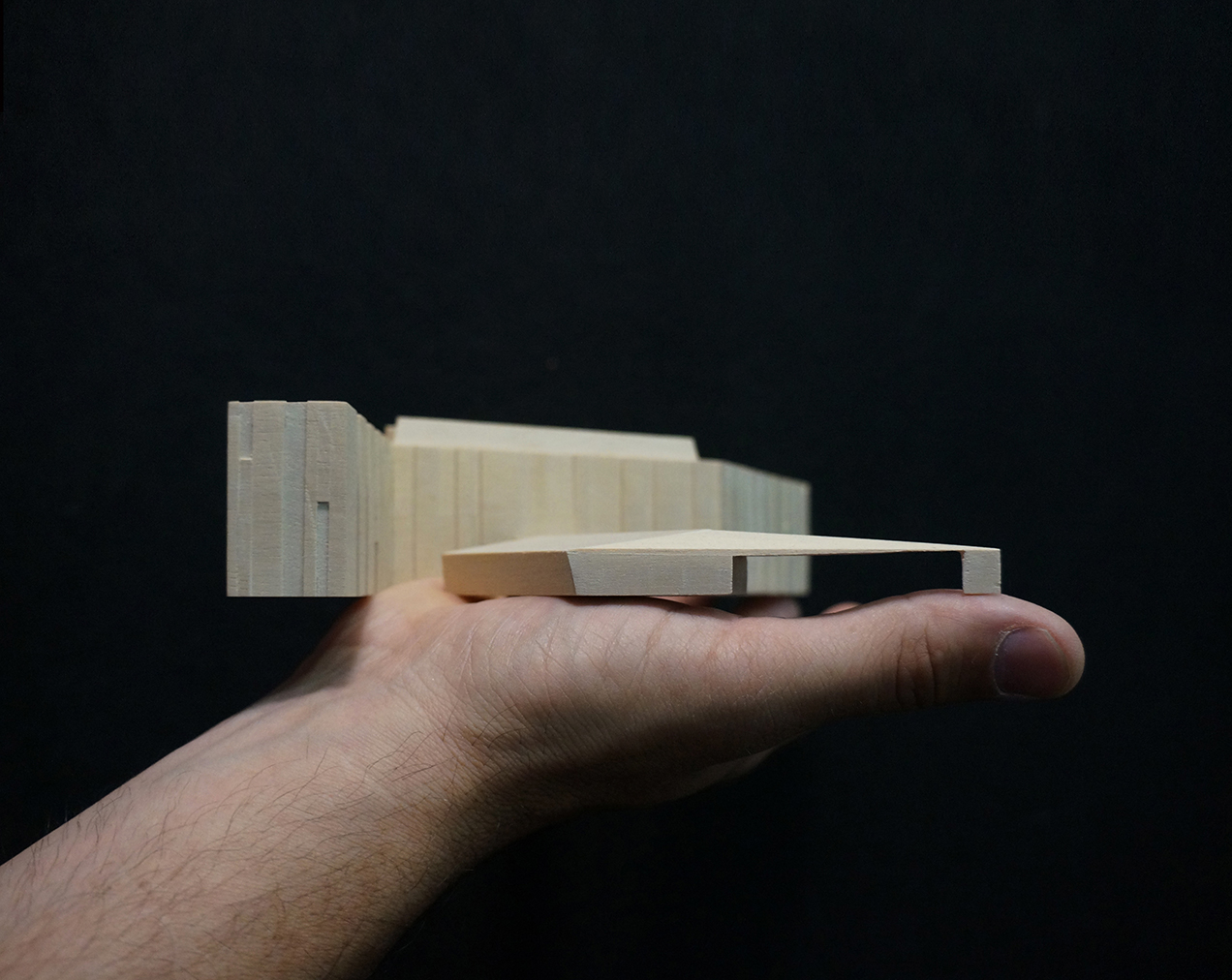

“We accept that as being de facto identity for the city—that’s the way we celebrate being here,” Public Architecture + Communication Inc. principal Brian Wakelin says of Vancouver’s aesthetic reputation. “In my opinion, it’s such a lazy form of public space and grew without a lot of intentionality. There’s not really a space where the city can gather and collect and do stuff beyond walking and moving continuously. We don’t have big spaces in the middle of the city where we can do things.” It’s not so much an axe to grind as it is a problem to solve, and the main reason Wakelin and his partners decided to apply for the prestigious Professional Prix de Rome Award in Architecture, which gives one Canadian firm each year the money it needs to explore other urban cities and report back on what the hometown can do better. “I didn’t think we would win at all,” Wakelin says with a laugh. But they did. (It’s been a good couple of months: the firm also just won a Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia Award of Merit from the Architecture Institute of British Columbia for its work on the Newton Field House in Surrey’s Newton Athletic Park.)

The Prix de Rome is awarded by the Canada Council for the Arts, and has been in the country since 1987, though its roots date back to a 17th-century travel scholarship. The national winner is chosen based on a firm’s previous work, its proposed plan, and if one cohesively fits with the other. With 2015’s $50,000 grant, the next step for Public is continued research and planning, until they take off for their first destinations next spring—Rotterdam and Oslo—and then Tokyo and Singapore the following autumn. Focusing on Vancouver, Wakelin and team chose cities that were similar in economy, politics, and relation to water. “Within those water-oriented, social democratic cities, it was, ‘What cities have grown up in a similar time frame to the place we know?’” explains Wakelin. “Rotterdam and Tokyo were really raised during Second World War—so much rebuilding took place after. They’re kind of ugly cities, in a way. It’s not like going to Rome.” Rome’s appeal is undeniable, but its stark historic differences from Vancouver made it less desirable for this research project. “I thought it was important to look at places kind of strangely familiar—they’re kind of awkward in their materiality,” Wakelin says. “They also came to be in the time of the automobile, and I think that’s super important that they had to deal with all those issues.” On the ground in each place, Public will meet with local firms and explore the spaces and places that make it move.

Wakelin’s curiosity for these other cities, and what he and his team might discover in them, is almost infectious. He easily rattles off various projects he wants to check out, from a Rotterdam market hall with an apartment complex bending over it, to an opera hall in Oslo which pedestrians can “walk through, around, and over in a relatively free and unencumbered way,” he says. “I’m so interested to see how one accesses these places. Do you go through a security check? Can you protest there? Can you be drunk there? Can you be homeless there?” The questions swirl around in his brain, and tumble out quick like a rolling rock along a hill. Hopefully at the bottom lies a pool of infinite possibilities.