Ellen Schwartz grew up in an urban Jewish family in New York. In the 1970s, she and many other disenfranchised youth of America decided to go “back to the land.” When Schwartz, her future husband, Bill, and their friends started a communal homestead in the B.C. wilderness, overnight they had to become loggers, cabin-builders, gardeners, chicken farmers, apiarists, and woodstove cooks. In her new book, Galena Bay Odyssey: Reflections of a Hippie Homesteader, the Vancouverite recalls the decade she spent working the land in the Kootenays.

One of our first priorities, after building the cabin, was to put in a garden. Bill, Paul, and I knew almost nothing about gardening, so we chose a pretty, sun-dappled, relatively flat spot about a hundred yards down the slope from the cabin. We hired Floyd Fitzgerald, owner of the sawmill, to clear about a quarter-acre.

“Dig about a foot and a half deep,” our neighbour Pat Harrington advised us. “Get rid of any rocks bigger than an egg. Anything smaller you can leave.”

No problem, I thought. The garden space was only about twenty feet by thirty feet. It shouldn’t take more than a few days to dig it up. And how many rocks bigger than an egg can there be?

Bill, Paul, and I marched out to the plot with spades and stuck them in the ground.

Clink.

We each hit a rock. I dug mine up. It was the size of a medium potato. Paul’s was the size of an orange. Bill’s was the size of a grapefruit. We tossed them to the side of the demarcated area. Thump, thump, thump.

Spade in again.

Clink. Scrape. Screech.

The tip of my spade lost purchase under the rock. I moved it slightly to the side and dug again. This time I manoeuvered it underneath. I pulled back on the handle. It didn’t budge. I tackled it from the other side. First I had to remove a bunch of smaller stones before I could get the blade under the other end. Creak. I finally pried up a rock the size of a spaghetti squash. I needed two hands to lift it and toss it aside.

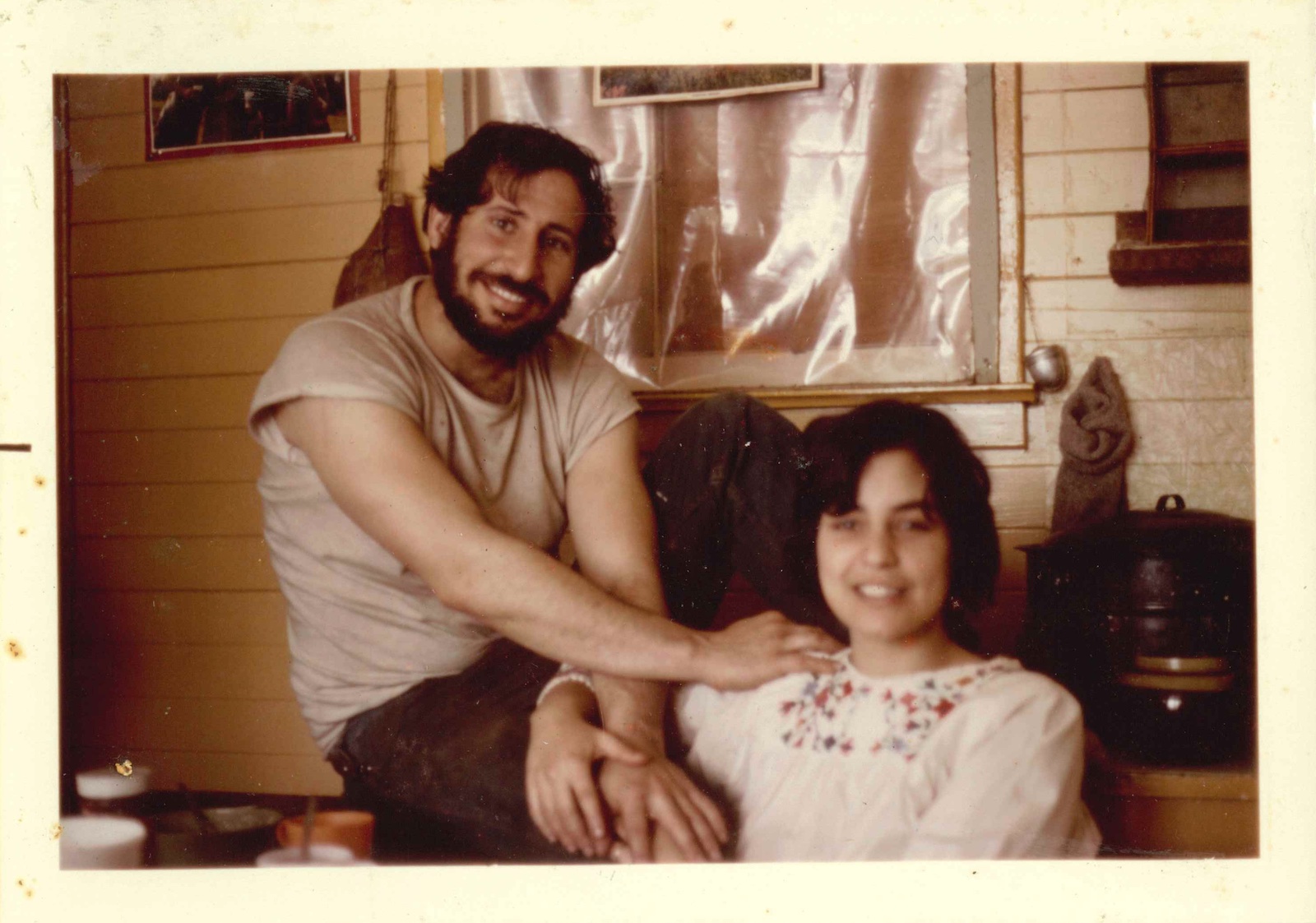

Ellen Schwartz and her future husband, Bill, circa 1973.

After a couple of hours, I was on the verge of tears. Bill caught my eye. “Hey, it’s a rock festival.”

I just groaned.

Paul leaned on his spade. “Yeah, I’m pretty stoned.”

“Rock out,” Bill said.

A giggle escaped me. I gave in. “Everybody must get stoned.”

Paul: “Rock around the clock.”

Bill: “They’ll stone you when you’re trying to be so good.”

Me: “Rockin’ robin, tweet, tweet, tweet.” I held the handle of my spade like a dancing partner and jitterbugged.

By now we were all laughing hysterically. This couldn’t be happening. It was. What else could we do but laugh—or cry?

Later, we went up to Bob and Pat’s. We sat at the table, trying not to scratch our mosquito bites, and told them about the rocks. They exchanged a look. Bob said, “Sounds like you hit an old creek bed.”

Bill’s voice was tight as he asked, “Would it have covered the whole lower part of the property?”

“No way of knowing,” Bob answered. “You could dig a hundred feet away and find good, rich soil.”

There was a pause. Pat said gently, “Didn’t you dig up some soil samples before you decided where to put the garden?”

Bill, Paul, and I looked at one another. “No,” Paul said in a small voice. “We didn’t think of it.”

“We thought it was a pretty spot for a garden…” My voice trailed off.

Back at the garden patch, we hefted our pickaxes and stood there, gazing at the cleared area. We didn’t speak but I know we were all thinking, How stupid could we have been?

Pretty damn stupid.

Day after day. Clink. Scrape. Screech. Some of them were so large that it took half a day of digging just to clear enough space to get under them. We couldn’t lift them out—we had to use a come-along hooked up to the truck to winch them out and pull them aside.

It wasn’t so much the physical work that was gruelling; it was the sheer drudgery of finding another, and another, and yet another stone. It was not knowing if it would ever end. It was feeling that I was not capable of doing this task, and being afraid to fail.

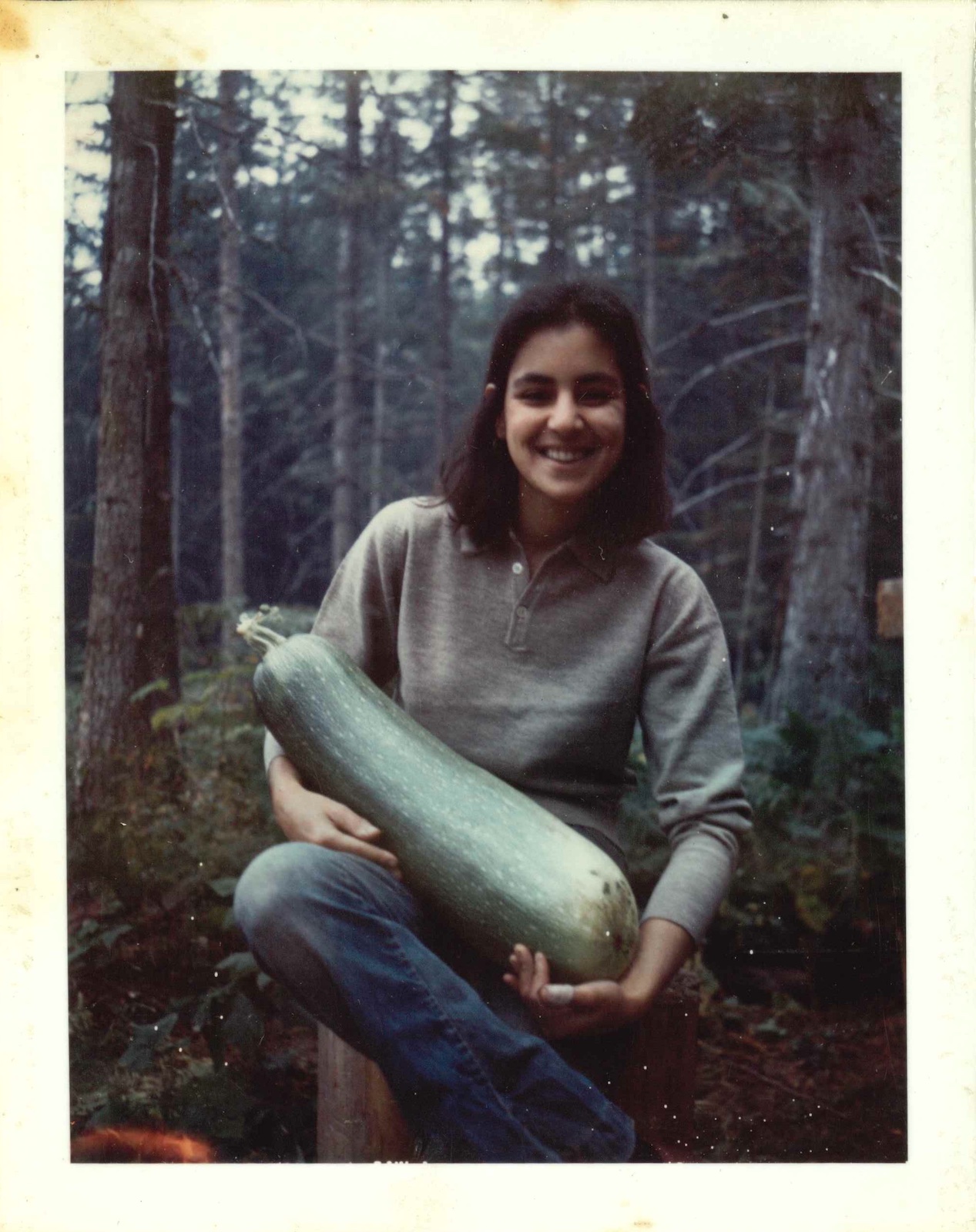

Bill with a bountiful squash harvest, circa 1977.

I didn’t quit. Quitting, not doing my share, being inadequate to a task—all of these are some of my deepest fears. So I forced myself out there, day after day, and after three brutal weeks, we finished. We had taken out so many rocks that the level of the soil in the dug-over part was lower than that of the surrounding earth, and what remained was clayey and grey, or rusty-red from iron. It didn’t look like it would support any kind of growth.

And it didn’t. That first year we planted broccoli and peas, carrots and beans, cabbages and zucchini, corn and potatoes. The shoots came up—and then dwindled to spindly, anemic-looking stalks.

When we consulted Walter to find out what the problem was, he said that forest soil was low in nutrients in the first place and that ours had become even more depleted when the top layer had been scraped off by Floyd’s skidder. “Build up the soil with compost, manure, and mulch,” he advised. But we didn’t have any compost. We had started a pile beside the garden, but its contents had yet to decompose. And it was too late in the season to apply manure.

That summer we harvested a few spindly carrots and a handful of beans. Slugs got the cabbages, and the corn didn’t even tassel, let alone produce ears.

In the fall of 1973, we set out to build up the garden in a serious way. By then we had a small but rich pile of compost. We bought three truckloads of horse manure, along with several bales of hay, and dug all of it into the garden. We became manure experts.

By the following spring, when we turned the garden over, the dirt was actually beginning to look like soil. We even spotted an earthworm or two. The next summer’s garden was better. We harvested modest crops of peas and beans, carrots and cabbages. We started a small herb garden, and by then we had our first flock of chickens, and we dug the manure-rich straw into the garden at the end of the season.

Each year our garden became lusher and more abundant. We dug baskets full of thick, long carrots and beautiful round potatoes, learned to put out containers of salt to trap the slugs and harvested large, heavy green cabbages, grew globular beets and turnips, and sowed a succession of greens.

The author shows off a monster zucchini, circa 1974.

We made one major mistake: we planted zucchini seeds directly in the compost pile. The zucchinis exploded. They grew inches every day. We couldn’t give them away fast enough. We couldn’t even feed them to the chickens fast enough. They kept growing, to the size of baseball bats, cudgels. I made stuffed zucchini, zucchini pickles, zucchini bread, zucchini cake. One night, after I had served the third zucchini dish in a week, Bill said, “You know what? I really hate zucchini.”

I nearly clobbered him with a club-sized zucchini.

Excerpted with permission from Galena Bay Odyssey: Reflections of a Hippie Homesteader by Ellen Schwartz. ©2023. Published by Heritage House. All rights reserved. All photographs courtesy of Ellen Schwartz.

Read more book excerpts.