A few months ago, I started to get a weird, heavy feeling in my throat. It felt a bit like loneliness and a bit like grief, like being on the point of tears. I recognized it because I’ve had it before: homesickness. But this time it was directed toward a place I’ve never really lived—Ireland.

As an Irish-born, English-raised, Canadian permanent resident who spent years living in Singapore and is now married to a Frenchman, the question of where home is has preoccupied me more than ever this past year.

I was born in Ireland to Irish parents, but we emigrated to England just before my fourth birthday. It was a well-worn path. People have always moved from Ireland to the UK or farther abroad to survive famine, escape poverty, and find their fortune. When we left in the 1980s, we were part of a wave of emigration of educated folk who, like my dad (who went on to practise as a doctor for 30 years), went to England to advance their careers.

We settled in Manchester, in the north of England, but the constant refrain was that we were Irish, this was temporary, we would never be English, this would never be home. Nor would we want it to be: while it was long past the era of rampant discrimination against the Irish, it was long before the era of the Celtic Tiger, when Ireland became a desirable place for other people to live.

We often experienced anti-Irish sentiment. My older brother developed an English accent within weeks of starting school because his classmates (ironically, most of whom were of Irish descent) said he was in the IRA. The stereotype that the Irish were feckless and drunk was ever present; back then the expression “a bit Irish” meant stupid or illogical. Irish people were said to be terrorists, excessively religious, cursed with an excess of children, superstitious, and backward looking.

The author, age 3, in Ireland. Photo courtesy of Aileen Lalor.

Over the years, my dad would periodically disappear for days or weekends for job interviews that never turned into jobs. My siblings and I lost our accents, and when we returned to Ireland in the summer or for Christmas we had become the English cousins, with different cultural references and slang. Yet in England, we were adamantly more Irish than everyone else—you could call us Plastic Paddies, though no one ever did.

My granny would send over shamrock from Ireland specially for St. Patrick’s Day. It was always wilted and soggy by the time my mum unpacked it from its padded envelope (I later found out it was grown in the Netherlands then shipped to Ireland). My brother, sister and I would stuff it in the pockets of our school shirts and look embarrassed all day, green with envy of our classmates with Irish flag ribbons in their hair and gold plastic harp brooches.

After more than a decade in Manchester, my parents conceded that the longed-for return to Ireland was never going to happen, and so we moved again in England for another job. Ireland was still home, but we acknowledged, without words, that we would never live there.

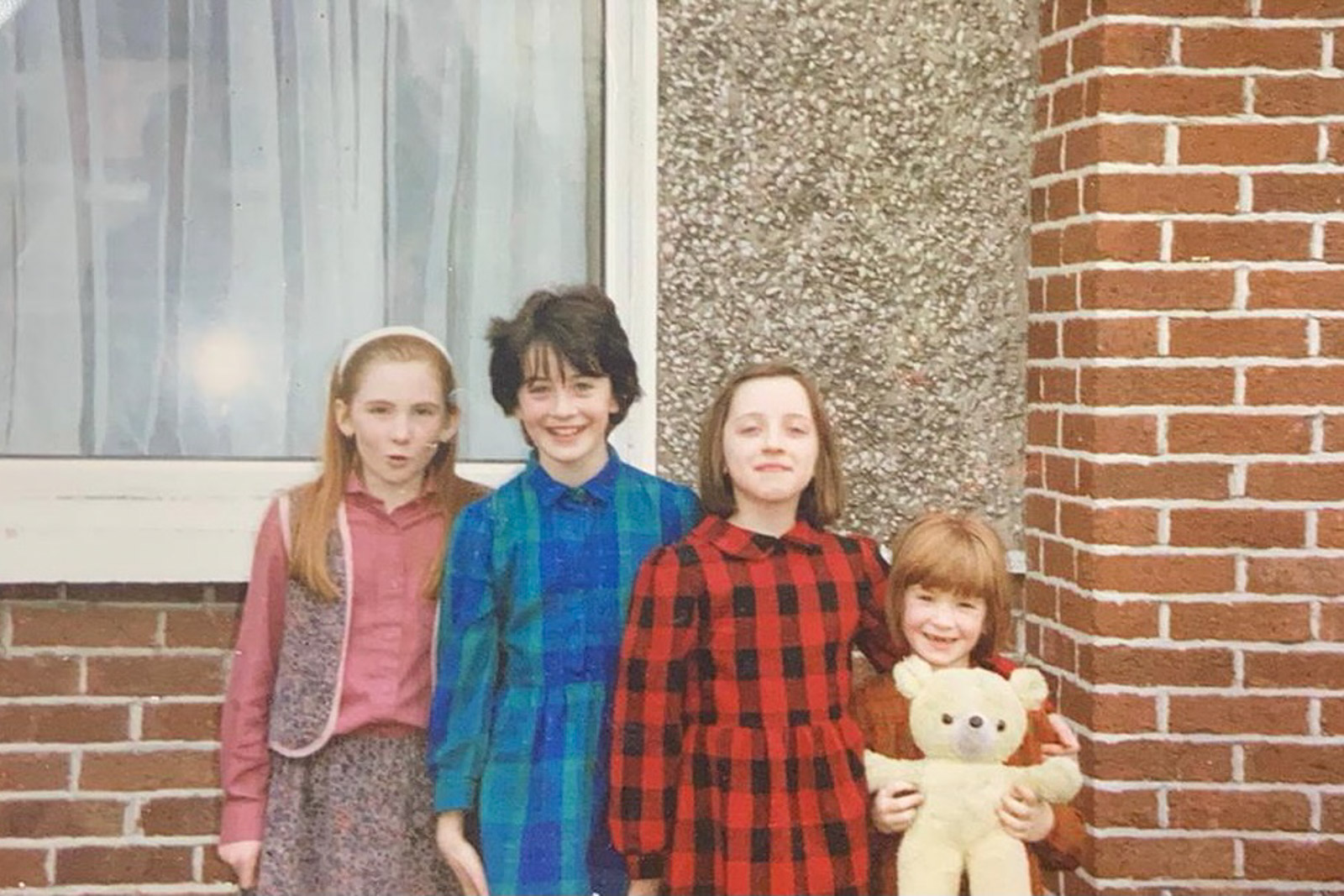

In Ireland with her sister Sinéad and their cousins Maeve and Doireann. Photo courtesy of Aileen Lalor.

Visits back to Ireland grew more sporadic as I got older and more entrenched in my own life. Of course there were childhood vacations, now remembered as endless sun-dappled days, surrounded by cousins, all roughly the same age as me and forced by family ties to be my friends. There were sleepovers and hours in the back garden on the swing set. There was the sense that you were very important and everyone wanted to see you. “Being ‘special visitors,’ us kids would be spoilt, stay up past our bedtime, and feel like every day was Christmas,” says my cousin Róisín, who lived in Switzerland between the ages of three and nine and spent most of her adult life in London before moving back to Dublin two years ago.

There were shared rebellions as we grew older, sneaking off for furtive cigarettes with one or another of my 19 first cousins or, later, to the pub with friends, where I got tipsy on gin and paranoid that some aunt or uncle would walk in.

On a trip to Ireland in the 1980s. Photo courtesy of Aileen Lalor.

My parents eventually retired to Ireland. After university in Scotland and a few years of work, I met my husband and together we emigrated to Singapore for four years. I landed in Vancouver eight years ago and had my two daughters here; Canadian passports are the only ones they hold, and my husband and I have applied for our citizenship now too.

These days I rarely visit Ireland, but I’ve been feeling a renewed connection whenever I do. I wonder if that’s the root of my enduring pullback—even now, almost 40 years since I lived there—and the reason I’m now feeling pangs of homesickness. Is it simple nostalgia? A deep sense of familiarity, as I show my own children the church in which their uncle received his First Communion, or the beach on which my dad proposed to my mum, or the neighbourhood my granny used to live in, where my mum grew up and most of her family still lives?

Is it that my ties to Ireland are stronger than my ties to Vancouver and I’m nurturing them more now with daily FaceTimes with my parents and sister, so the rope pulling me to Ireland is stronger than the anchor holding me here? Or do I just feel the same as everyone else: a bit trapped?

My cousin Maeve has led a more nomadic life than I have: born in Ireland but raised in Belgium, at 18 she went to university in Ireland and spent a summer in New York before moving to Africa for a while, then to London, Uzbekistan, London again, and now Washington, DC. In spite of all the travelling, Ireland has always been the place she called home—but never with the sense that she had to actually live there.

Like me, Maeve experienced only occasional homesickness until now, when she suddenly feels marooned. “I’ve always said to my parents, wherever I’ve been, even if I’m in Timbuktu, it doesn’t matter what happens, if there’s an emergency, please tell me; I can always come home, and the world is so small, I could be home in a day,” she says.

“Suddenly I find myself unable, or the logistics seem so difficult that it feels overwhelming. I’ve felt such heart-wrenching sadness at not being able to bring my parents things. An apple tart on the doorstep, or just to ring the doorbell and say hi. It has changed. It has changed my relationship with feeling comfortable being far away.”

My sister feels similarly. “The way that the pandemic affected me most in terms of home was when I was still living in Germany, in the first lockdown this time last year,” she says. “I suddenly felt so far away that I just couldn’t go home. It felt like it might as well have been Australia.”

“I came home in August for my birthday for three days, and it made me really homesick,” she continues. “It feels like a deep, raw sadness.” After several years away from Ireland, she moved back home in November, when the second German lockdown hit.

“The resolution of homesickness is that feeling of release and relaxation. That feeling of: thank god I’m here,” she says now.

The author, top right, with her mother, sister, children, and nieces at her parents’ 70th birthday party in Dublin in 2019. Photo by Nicola Ross, courtesy of Aileen Lalor.

Dr. Paolo Boccagni, a professor of sociology at the University of Trento in Italy, cautions not to romanticize our ancestral homelands too much, something I know I’m guilty of doing. That feeling of home may be less related to the real characteristics of a place and more tied to what we imagine it to be, he says.

“Perhaps we are socialized to find a place important because of our family connection,” he suggests. “Diasporas often have a symbolic or emotional attachment to a place. Or maybe it’s a place where you went on holiday, but if you actually lived there, it’s not so great.”

My cousin Roísín concurs. “Growing up in Ireland from the age of nine felt entirely different to everything I had known in Geneva,” she says. “Sadly we were no longer feted and spoilt by extended family, and I missed my old life, the friends, school, and even the supermarket. Possibly that was a sense of homesickness, even while I knew I was ‘home.’”

Boccagni’s research largely focuses on migration and the search for home, and he offers the important reminder that all of this is—my words not his—privileged navel-gazing.

“Having a specific place, a piece of land that you can claim as home is more important the more people are in vulnerable and disadvantaged positions,” he says. “They need something tangible to rely on. They have fewer resources to adapt themselves. There’s a fundamental difference between what I expect as the sense of homelessness of the intellectual or entrepreneur or skilled person who can adapt, and the very practical homelessness of the person who has no place to exert control. I respect the spiritual dimension of the homelessness of the well-to-do, but it is not the same thing.”

He also points out that, living on colonized land, we need to look at the place through a different lens. “In nations such as Canada and Australia and the U.S., who is the native? Who is to claim nationality? How are we here and now? Whose home has been the place we are in now? And how does this acknowledge the rights and memories of other people?”

Boccagni encourages immigrants of all backgrounds to consider reframing home as something ahead of us. “Think of it as something we are trying to build, rather than just where you come from,” he says.

I find my cousins’ effortless integration of their international experiences—something I’ve never really asked them about before—inspiring. “Part of living in loads of countries is being proud of my identity,” Maeve says. “I feel Irish; I feel European. I’m comfortable in myself when I’m in other places. I feel like I am a foreigner, and I celebrate and enjoy that.”

It’s a lesson for me: to know that my identity is complicated but no more so than anyone else’s. To recognize the inherent instability of being a human (what a lesson to learn now)—that everything is transient, that stability is not the natural state of things, and that ultimately I am lucky. Lucky for this chance to help my children be proud of their half-Irish, half-French, and all-Canadian heritage. Lucky to see my own world travels as a gift and an opportunity to learn rather than a burdensome life story that takes too long to tell.

Read more Essays.